Ask any beleaguered post-Covid museum director what they need right now, and they will likely be quite blunt. They need visitors to come back and staff to stick around. They also need a functioning building with the funds to maintain it, and as they are museum directors, they want that building to be beautiful. And they need tools for wrangling the complexities of the world on their doorstep.

As it turns out, what many mean when they say all this is: we need Annabelle Selldorf.

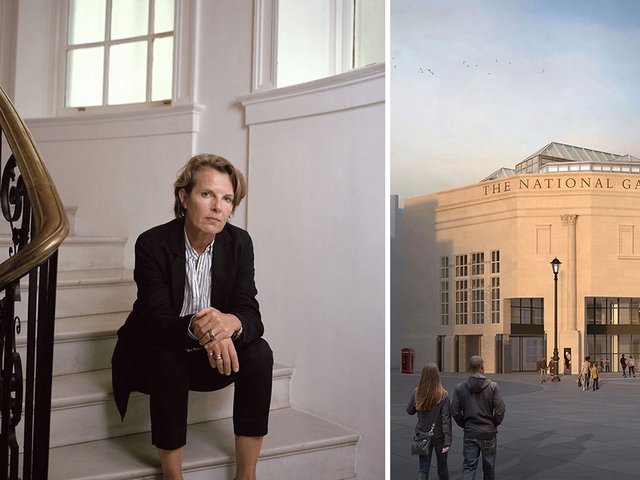

The New York-based Cologne-born architect is at present working on the revamp of the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, DC, along with the new wing of the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts, and the expansion of the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto. She is also celebrating two big museum reopenings: her renovation of the Frick Collection in New York on 17 April and her reworking of the Sainsbury Wing at the National Gallery in London on 10 May.

Recent plaudits include Selldorf projects being nominated for an ArchDaily 2025 Building of the Year Award and netting a Public Design Commission Award as well as spots on the Wallpaper* USA 400 list and Architectural Digest’s AD100 Hall of Fame list.

Selldorf’s Frick staircase: “A beautiful staircase is not about wowing someone but about being a really excellent staircase” © Nicholas Venezia

Small wonder, then, that some newspapers have taken to unpicking the dated portmanteau term “starchitect” and describing Selldorf as a “star architect” instead. Clumsier, sure, but accurate. She is, headlines increasingly proclaim, the art world’s favourite, the architect of our moment.

“Isn’t it awful?” she says. I mean, I really don’t know what that could possibly feel like, so I don’t reply. “Very deeply embarrassing” is how she puts it. I laugh, and while she doesn’t exactly, her candour and warmth are magnetic.

We’ve just emerged through the security turnstiles at the construction site entrance to the Sainsbury Wing. It is the first day of spring. The air is thick with sunshine, buskers and protest. I’ve taken a punt and suggested we continue the interview on foot, to which she instantly, brightly, agreed. We’re headed to see the pelicans in St James’s Park.

Curators and institutional directors across the US and Europe have, over the past couple of weeks, told me Selldorf is attentive and pragmatic, not the most vocal person in any meeting, but that when she does speak, everyone pays attention. The director of the National Gallery in London, Gabriele Finaldi, says she’s a genius in human relations and a true collaborator.

Selldorf says it’s about an allegiance to specificity. “You can only be specific if you have perspective. What I love about working in museums, with art and curators and directors, is that the dialogue is very intimate. The way to gain perspective is to really understand what matters to them.”

That sense of intimacy is palpable. First off, everyone I speak to has either just had dinner with her, is about to, or met her in the first place at a dinner party. By the end of the gruelling public consultation process required to get the Frick project off the ground, the newly retired director Ian Wardropper says he and Selldorf were “like an old married couple, finishing each other’s sentences”.

She gets it

More than any trend-adjacent infatuation, what these museum workers—and that is, quite profoundly, how she sees them—collectively seem to be expressing is a great big sigh of relief. Selldorf gets art, from the inside. And museums are, and always have been, like a second home to her.

Architecture as a service rather than a statement: Selldorf’s lobby design for the National Gallery’s Sainsbury Wing Photo: © Selldorf architects

When Selldorf was invited to give the National Gallery’s 2023 Linbury Lecture, she chose to structure it as an enfilade of museum interiors: a tour through the seven institutions that have meant the most to her, starting with the Wallraf-

Richartz Museum in her home town of Cologne. She grew up, she said, in a family that “preferred going to look at exhibitions rather than doing just about anything else”. The Wallraf-Richartz was part of their lives, its walls and contents as foundational as whatever was going on at home. Home, meanwhile, embedded the importance of art and making. Her father got his architect’s licence the hard way, through practice, not academic study. Her mother studied art and became an interior designer. The great German artist Sigmar Polke was a friend.

It makes perfect sense then that the greatest compliment she says she has ever received was from Richard Serra

It makes perfect sense then that the greatest compliment she says she has ever received was from Richard Serra. “You’re the architect?” he asked, standing in David Zwirner’s 20th Street gallery. She said yes. He said, “Good job.” So too, the fact that, listed among her seven favourite museums is “the world of Donald Judd, in Marfa, Texas”.

“I don’t think of Judd as an architect,” she says, “but there was something about his unequivocal belief in space that was very profound.” She loved the insights Marfa yielded in terms of ways of thinking about making art, exhibiting art and living within art, with the artist’s “generous yet insistent presence”, she said in the lecture, “touching it all”.

Walk through a space under construction with Selldorf and you’ll see her as an artist too. When I ask about the large, framed elevation drawings in the Sainsbury Wing fire escape staircase, she says: “They’re Venturi and Scott-Brown’s [the architects of the Sainsbury Wing] presentation drawings. You can tell they were done by hand, with ink. These are going to have to change, which is really a shame, they’re so beautiful.”

Later, she’ll explain that the curved cutouts of the mezzanine floor that now sits above the foyer directly reference a “curvilinear movement” in Venturi’s early sketches. Their organic flow and lightness of touch—the “golden haze”, as Finaldi puts it, of this newly opened space—bring to mind the way Selldorf has described her intentions for the ceiling she’s given the Frick’s new auditorium in Manhattan. “The idea was always that it would look like the sky,” she has said, “when you cannot identify the colour, when it brings a sort of notion of infinity to it.”

Of course, changes to the National Gallery have been controversial from the get-go. Selldorf’s plans have displeased even Denise Scott-Brown. Critics have downplayed Selldorf’s aims to make it a comfortable, welcoming space while sniffing how aesthetically it would be “an architecture of near emptiness”, “capably done”.

But that is to ignore why museums seek changes like these and why their directors keep asking her to make them. She says, “it’s a fundamental disposition not everyone agrees with”, that architecture is a service.

If you’re preoccupied with defying convention, you might miss the opportunity to do something that actually makes a difference to peopleAnnabelle Selldorf

“Architects like Le Corbusier were incredible at creating very expressive, sculptural buildings. Le Corbusier took all the liberty in the world and defied convention. But if you’re preoccupied with defying convention, you might miss the opportunity to do something that actually makes a difference to people.” In other words, it is how you live — and work, and live with art, and exhibit your work, and experience works by others— in her spaces that matters most.

Project driver

When Zwirner started out as an art dealer, Selldorf was the only architect he knew. They were both young and from Cologne, learning English in New York at the same time. So their working relationship began as a thing of convenience. But he has continued to commission her ever since. “I have twice started projects with certified starchitects which did not come to fruition,” he says, “and they will not be named.”

At present they have two projects underway, a tiny one and a very big one. For the past two decades, Zwirner and his family have lived in a Selldorf-

designed home. “If you don’t move for 22 years, you must feel pretty good in that home,” he points out. Maybe he can never move his galleries either or will just have to keep collecting them like beads on a necklace, given they’re all designed by Selldorf too.

Seasoned professionals such as the New Museum’s Massimiliano Gioni, who routinely go to exhibitions in spaces like Zwirner’s as part of their day jobs, say that what makes the venues so impressive is how well proportioned and lit they are from the outset. One month you’ll see the 20th Street gallery emptied entirely for a Richard Serra show, and the next, reorganised to host Morandi’s diminutive still lives with bottles. The respective works’ demands could not be more opposite but the bare bones of the gallery can still fully bridge them.

Gioni makes the point that what allows Selldorf to deliver this is both her willingness to listen—and change her mind if convinced—and ability to stand firm when she knows she’s right.

They met at a dinner party in New York in the early 2010s. As the curator of the Venice Biennale in 2013, Gioni was trying to figure out how to neutralise the Arsenale’s overly dominant space, which, to his mind, had become a genre unto itself, with “dark environments, big wow pieces, quite repetitive”. Selldorf offered to help—for free—so they started meeting weekly in her office. She’d roll tracing paper along the full length of a table (“because the Arsenale is so long”), tape it in place and start drawing.

“I used to joke that she was my therapist,” Gioni says. “Just to have an hour of actual devoted thinking about the space was very special.” She insisted on an overhead fabric scrim to lower the ceiling of the Arsenale, diffuse the light and calm the space. He was nervous, he says, but it worked exactly as she said.

Selldorf then took the idea to Frieze Masters, fairs being another overwrought environment. There too, Old Master dealers in particular were resistant. Being given a limited colour palette didn’t sit well with their desire to stand out visually. “It took a while,” she says, “for people to realise that if the overall atmosphere of mild daylight in this public sphere was calm, then the overall experience was better.”

She surveys both staff and people who never go to museums. “Exciting,” she says, “is, by and large, a positive word. But I think it’s a fleeting word. I am slightly more interested in the longer-lasting. How we are toward others, making room to listen to people: all of that compounded creates an attitude that is less ego-driven. I sometimes think maybe,” she pauses for eight whole seconds, “maybe that’s weak? But it’s all I have, so it’s not going to change any more.”

Back in 2014, Selldorf scoffed at the idea of an architectural “wow factor”. “I love to build a beautiful staircase,” she said, “but it’s not about wowing someone, it’s about a really excellent staircase.” A decade on sees her unveiling precisely that at the new Frick: a cantilevered correlate, in veined, Breccia Aurora marble, to the 1914 mansion’s grand original staircase.

As I leave her outside Bond Street station, she looks me straight in the eye and says: “I’m not afraid of asserting myself. But it’s not about wanting to be powerful for the sake of it. There has to be a reason.”