The paperback edition of Kingsley Amis’s novel Lucky Jim quoted glowingly from a review by William Somerset Maugham. Amis, purred Willie, was “so talented, his observation so keen, that you cannot fail to be convinced that the young men he so brilliantly describes truly represent the class with which his novel is concerned”.

Somehow, Amis’s publishers failed to find room for the rest of Maugham’s paragraph: “They do not go to the university to acquire culture, but to get a job, and when they have got one, scamp it ... Their idea of a celebration is to go to a public house and drink six beers. They are scum.”

The protagonists of Art, Peter Carty’s ironically artlessly titled novel of the 1990s Shoreditch/Hoxton Young British Artists scene ring similarly true, and are for the most part similarly unprepossessing. A couple of the artists seem genuinely committed to their work, or that’s what they tell themselves, but the general sense is of the kind of non-specific will to power that one encounters in youngish Londoners of every generation, and which might just as well find expression in TV, club promotion or pop-up supperclubs as in fine art – it just depends what’s happening, or rather Happening, at the time. Throw money, sex, violence and drugs (lots of drugs, in this case) into the mix, and the result is a toxic and potentially—why yes!—explosive cocktail of desire and betrayal.

Squalor in Shoreditch

If you’re reading this on a print or digital subscription to The Art Newspaper, chances are you remember such people. I myself used to tramp round private views in greasy short-let spaces, and drink in Home, the Griffin and the Dragon Bar. For me, this book evoked with a Proustian rush the sheer squalor of the scene: the sticky chairs, the beer cans garlanded with butt-ends, the studiously toneless drivel everyone talked. Something of that scuzziness survived in the best work of the time, transfigured into a grander sentiment; something about fragility and loss and defiance.

Developers rolled into these flimsy ecosystems like so many Panzer divisions, cashing in on the outsider energies of the art scene even as they contrived to demolish the conditions that had made it possible

Gentrification swept it all away, of course. Art is shrewd about this; about the way collectors jacked up the market, their largesse trickling down to tame gallerists and curators, who migrated westward from spaces that looked like black sites for terrorist interrogations to ones that looked like high-end boutiques, which is essentially what they were; about how the developers rolled into these flimsy ecosystems like so many Panzer divisions, cashing in on the outsider energies of the art scene even as they contrived to demolish the conditions that had made it possible.

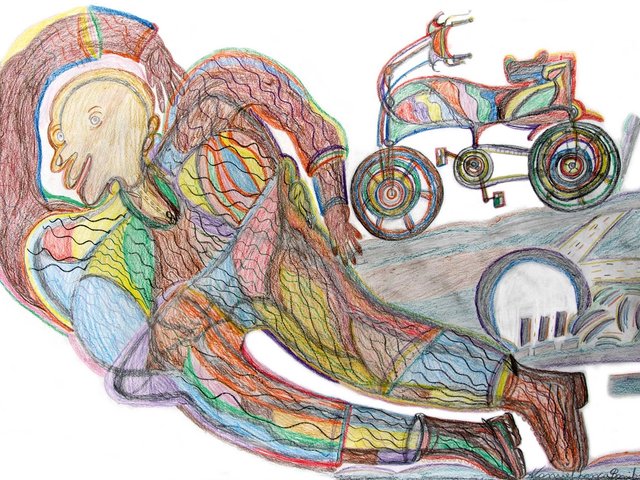

It is also more or less the only novel about modern art I can recall reading in which the works of art that feature sound more or less like actual works of art that an actual artist might have produced at the time. This is a trickier feat than it sounds—something to do with not describing things too fully, I think—and one of many things that lend this book a compelling insiderish quality.

But the real heart of tales like these is the passage of a few people through a short period of time, as Guy Debord has it. Here, Art is a mild disappointment. Billy the sort-of narrator, who in occasional flash-forwards we see back home in Essex some years later, chewed up and spat out by London like so many others, is defined not so much by his character, wishes and fears as by the rampaging cocaine habit that bears him tumultuously along. (In fact the book might as well have been titled Coke as Art.)

And Becky, with her charismatic scar and intriguing dual heritage, who fizzles into success, first as an artist and then a (clearly unreliable, in the view of several interested parties) memoirist, is by no means a hollowed-out male fantasy, unless you’ve been to art school, though her vagueness about her work and her success did remind me a little of Connell in Sally Rooney’s Normal People, who is arguably a hollowed-out female fantasy if you’ve studied English at Trinity College Dublin. Several characters are vivid grotesques, but we don’t really get to see whether they are more than that.

There’s an odd sense in which Art reads as an intelligent pastiche of pop-culture-savvy literary-ish fiction rather than the thing itself

There’s an odd sense in which Art reads as an intelligent pastiche of pop-culture-savvy literary-ish fiction rather than the thing itself. Perhaps it’s conceived as Art rather than Lit; perhaps the cynicism of the characters pervades the enterprise. It scarcely matters: it’s an entertaining enough read, though it is somewhat in thrall to other and better, or at least more luminously original, work—from Stewart Home’s speed-fuelled, ultra-violent essays in the paranoid style (Art postulates a devilish and distinctly Homelike conspiracy between developers, gallerists, gangsters, fascists, Special Branch, Uncle Tom Cobley and all) to Irvine Welsh’s comédie sub-humaine (everyone’s constantly dobbing each other in to the Inland Revenue or the housing office), to the lurid urban baroque and Dostoevskyan doublings of early to mid-period Martin Amis, like his father, the recipient of a Somerset Maugham Award. We don’t know, though, what Willie would have thought of London Fields or Dead Babies.

• Peter Carty, Art, Pegasus, 280pp, £10.99 (pb), published 29 February