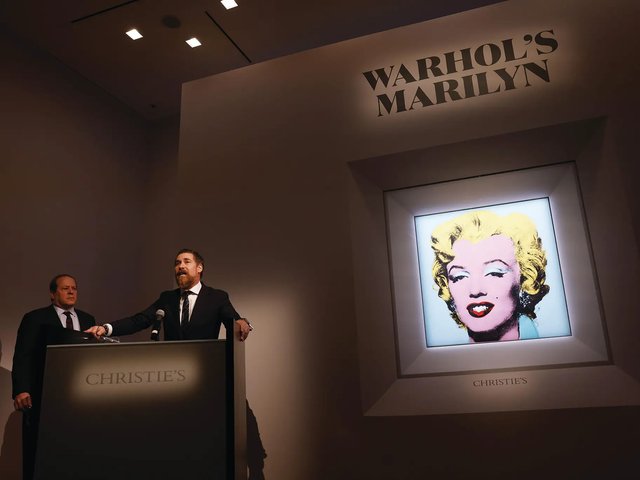

It is a coincidence—but serendipitous—that just as Christie’s hammered down at $400m for Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi (1490), the follow-up to Georgina Adam’s 2014 book, Big Bucks: The Explosion of the Art Market, has been published. Big Bucks explained the extraordinary rise in prices for the most desirable works of art. Adam’s new book, the Dark Side of the Boom, peers into less edifying corners of the art trade. It opens, again coincidentally (the book went to press before the Leonardo sale), with a discussion of what Adam calls the ongoing “titanic battle” between “Freeport King” Yves Bouvier and the billionaire Russian owner of Monaco football club, Dmitry Rybolovlev. Rybolovlev was the consignor of the Salvator Mundi to auction on 15 November.

As well as owning freeports—huge, tax-free storage units—in Luxembourg and Singapore, court papers have revealed that Bouvier was quietly trading art on the side. Among his sales was the Salvator Mundi to Rybolovlev for €120m. Rybolovlev has presumably done very well out of it—though, as Adam explains elsewhere, the possible existence of middlemen in high-profile sales means this conclusion is not as certain as it might initially appear. What is clear is that some of Rybolovlev’s other purchases from Bouvier—for very high prices—have made heavy losses when resold. The pair continue to accuse each other of nefarious, even illegal, activities while robustly defending their own innocence.

Fall-outs between buyers and sellers are not new, nor is buying art principally for investment: the first art fund was set up in Paris as long ago as 1904. But Adam argues that the number of super-wealthy people being tempted to buy art for both profit and cachet has reached record levels. This group of people—often surrounded by a courtier class of advisers, dealers, auctioneers, even ambitious artists and curators, and with huge sums potentially at stake—are ripe, she implies, for exploitation. Others, such as the collector and curator Stefan Simchowitz, who Adam meets in Los Angeles, are themselves motivated by the thrill of the deal. They take an active hand in the market, seeking to spot emerging artists and trends, and buy and sell works fast in a process known as “flipping”. (Simchowitz tells Adam that he seems himself as a “disruptor”, bringing more people into a market currently controlled by a self-regarding elite.)

Georgina Adam's Dark Side of the Boom "peers into less edifying corners of the art trade" Lund Humphries

Adam documents behaviour from the unethical to the illegal, from the consequences for young artists, picked up early, heavily promoted, but dumped by the market when their work falls from fashion, to the activities of fakers—and the questions this raises about the galleries and other experts who failed to spot their handiwork.

The Dark Side of the Boom is an information-packed, page-turning read. Adam—who has spent years as a specialist writer and editor on newspapers (including this one)—chooses her case studies well. But what she is writing about is profoundly depressing. It is with a shudder, for example, that we read the art dealer Simon de Pury saying: “I know some Rothko buyers who didn’t know who Rothko was until he reached $40m… suddenly they said, ‘this is really interesting!’.”

Adam makes it clear that this just a very small section of the market, and the people involved are the 1% of the 1% of the 1%. It is a world that is unrecognisable to the millions of people who go to shows, the art lovers who join museums such as the Tate, the thousands of artists, curators, writers and traders who feel privileged to make a modest living in the art world. But it is a world, Adam argues, increasingly distorted as art grows ever closer the luxury goods industry.

In April this year, Britain’s most successful living artist, Damien Hirst, mounted a fantastical exhibition in the publicly accessible, but privately funded, Pinault Collection in two huge spaces in Venice, with all the works, discreetly (but expensively), for sale. François Pinault is, of course, a luxury goods magnate, the owner of Christie’s auction house, a collector and soon-to-be owner of a third museum. Adam describes the run-up to the show as “the build-up to a new product launch”, and asks: “If art is just about making a marketable product, then what is the point of curation, scholarship, art criticism or art history?”

For now, the Hirst show remains a hard-to-repeat one-off. But if the Dark Side of the Boom is right, it may prove directional, a signal of much more to come. We have been warned.

• Dark Side of the Boom: The Excesses of the Art Market in the 21st Century, by Georgina Adam, Lund Humphries, 232pp, £19.99 (pb)

• For a discussion between Georgina Adam and Jane Morris on Dark Side of the Boom, listen to The Art Newspaper Weekly podcast