The book Outside In: Exploring the margins of art presents works by a group of mostly contemporary “outsider” artists and argues a case for critiquing them on merit—and the outsider art category in general—within the mainstream of the art canon.

Marc Steene, who trained as an artist at the Slade School of Fine Art in London and was for several years the executive director of Pallant House Gallery in Chichester, is the vice-president of the European Outsider Art Association and founder of Outside In, a charity for artists disadvantaged by mental, physical or social disability.

The nub of Steene’s argument is that their work, viewed through the prism of their condition, is unjustly dismissed as a therapy by-product, discounting its artistic creativity and creating barriers to fair market valuation and access.

Challenging the conceptual divides between normal and abnormal, marginal and mainstream, Steene makes reference to artists with a foot in both camps, including Goya, Vincent van Gogh and Grayson Perry (whose interview with the author forms a coda to the book).

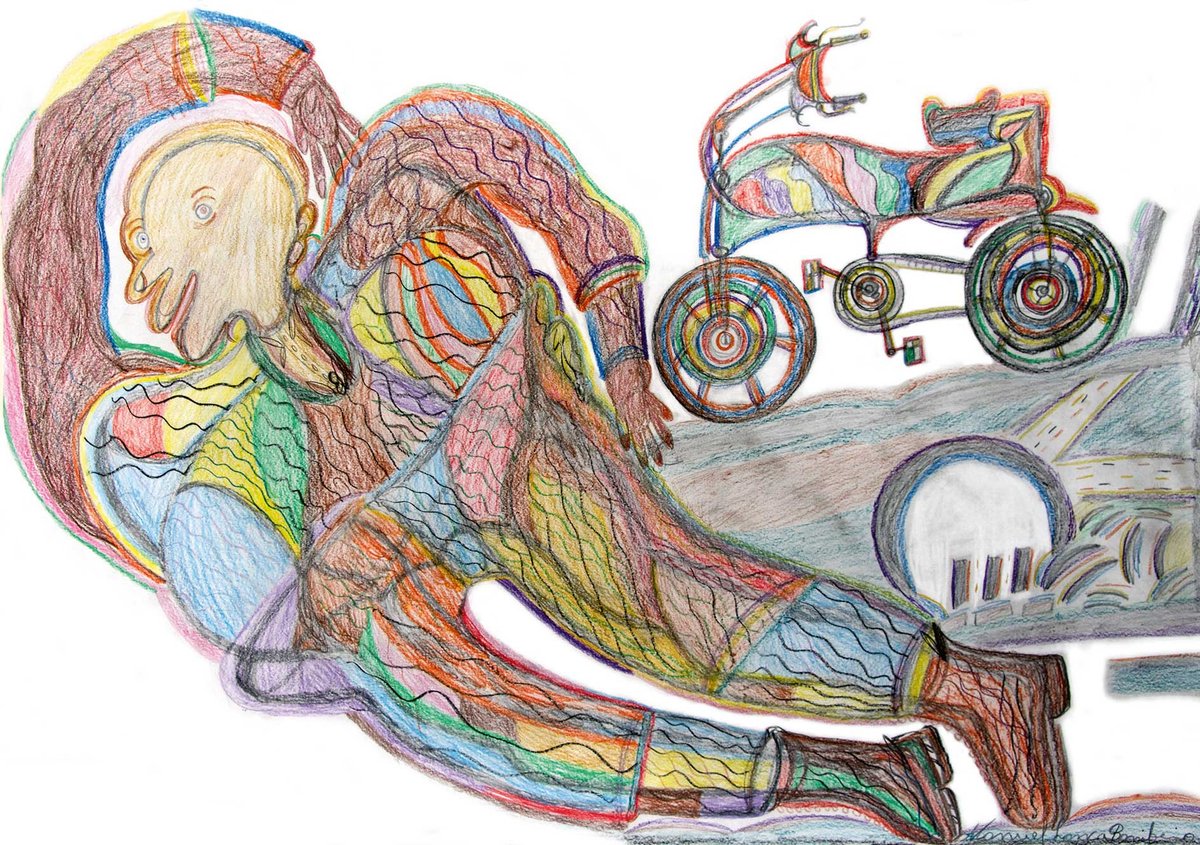

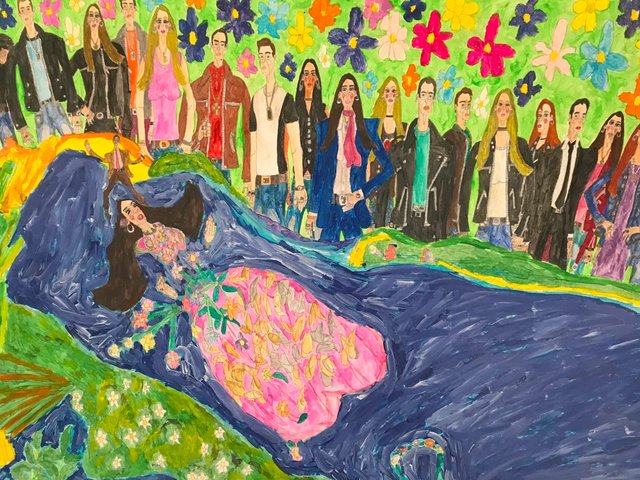

The 32 living artists and dozen or so historical exemplars presented are a disparate company working in diverse styles and materials, reflecting the catch-all nature of the outsider label and Steene’s thesis that they belong to a creative spectrum rather than a world apart. They include Wilhelm Werner and Julius Klingebiel, victims bearing witness to Nazi Germany’s sterilisation and euthanasia programmes, and Laila Kassab, a qualified psychologist born and raised in the confines of Gaza’s Rafah refugee camp. Some, like Dannielle Hodson and Jonathan Pettitt, are art college graduates. Most, like the Portuguese-born Manuel Bonifacio, the Romany gypsy James Gladwell or Rakibul Chowdhury, a child of Bangladeshi migrants, are self-taught or members of therapy and community art groups. One is a former prisoner; another, disabled and queer, is trapped in her bed by compulsive obsessive anxieties. Several, like Tess Springall, Nick Blinko and Albert Rackett, are patients, former patients or former staff of psychiatric institutions. Friedrich Nagler is haunted by ghosts of the holocaust; Joanna Simpson’s “gum nut folk” memorialise the lost children of Australia’s stolen generation.

Though many of the artists in the book are neurologically divergent, Steene rejects the popular concept of the artist as “mad genius,” noting that Van Gogh painted his masterpieces in the periods of lucidity between bouts of illness. The idea of the artist-genius-obsessive as a breed apart, he argues “does nothing but perpetuate … the stigma attached to madness”.

Steene structures the core of the book into three chapters, titled “Intuition”, “Introspection” and “Insight”, characteristics that he sees as intrinsic to the unmediated self-expression of outsider art. Clearly these are not exclusive hallmarks of outsider identity—consistent with his basic premise that they are qualities common to the spectrum of artistic expression. Still, they provide useful triangulation points for an understanding of its creative energy.

For historical perspective, he pays tribute to the clinical art collection of the early-20th-century German psychiatrist and art historian Hans Prinzhorn, whose landmark 1922 publication Artistry of the Mentally Ill profoundly influenced the Surrealists and the Art Brut painter Jean Dubuffet. He acknowledges, too, the role of the Modernists Ben Nicholson and Christopher Wood in championing the artistic integrity of the “naive” painter Alfred Wallis; and the importance of Adrian Hill’s 1945 publication Art Versus Illness in promoting the idea of artistic creation as catharsis after the Second World War.

The focus on individuals has its limits. He sets some philosophical hares running—is obsession a disorder, for example, or a necessary condition of creativity?—but he doesn’t give much space or time to chasing them. While the appropriation and repurposing of everyday materials is noted, or the creation of symbols to express the inexpressible, there’s little exploration of art-historical or art-theoretical sources and analogues. No discussion here of outsider art as Arte Povera, or the hermeneutic phenomenology of Paul Ricoeur. The aim of the book is more practical than conceptual. If establishment gatekeepers determine who is in and who is out, how do artists on the periphery cross the invisible threshold to market acceptance? Many of these artists, he notes, lack the capacity to navigate the art world. Rather than developing a theoretical integration of outsider art into the historical and philosophical canon, doesn’t it come down to having a curatorial patron or a savvy dealer?

Steene recognises the question: it is why he created the charity Outside In as a platform for marginalised artists, organising shows of their work since 2007. “Labels are always problematic,” he says. “The term outsider art is loaded …In its art-historical context it is used to describe art that has been created independently of accepted contemporary practice, outside the established canon … I have sought to highlight individual achievement rather than defaulting to any collective descriptors, whether societal or cultural.”

It may be either a pity or a blessing that Steene does not tackle the broader issues of sociocultural-philosophical analysis. Still, within its chosen scope, this book is a useful reminder that they exist.

• Marc Steene, Outside In: Exploring the margins of art, Lund Humphries, 128pp, 118 colour & b/w illustrations, £35 (hb), published 4 October 2023

• Claudia Barbieri Childs is an independent arts reporter and critic, living and working in the UK and France