This book publishes the proceedings of a conference held at the Victoria and Albert Museum that coincided with the museum’s 2016 exhibition Botticelli Reimagined. The purpose of both the exhibition and the conference is stated with admirable clarity by Ana Debenedetti, a co-organiser of the former and co-editor of the present volume: “The process of redefining Botticelli’s art is part of a wider modern phenomenon which extracts works of art from historically grounded settings and inserts them into new, ‘contemporary’ narratives… Displayed alongside modern and contemporary works of art, historic objects are further isolated from their primary function and locus. Through such display, these works gain new audiences and meanings, simultaneously casting new light on the contemporary pieces presented alongside them.”

The process of redefining Botticelli’s art is part of a wider modern phenomenon

I would take it that by a “wider modern phenomenon” she means Post-Modern, entailing the appropriation of works from the historical canon into later contexts and meanings, unrelated to their original function and purpose. The exhibition was arranged in three parts—from Botticelli and his workshop through his revival by the pre-Raphaelites, Pater and the English Aesthetic Movement, to Post-Modernism and Pop culture.

The gathering of papers published here follow the same rubric, adding a fourth part introduced by Caroline Elam, the book’s other co-editor, entitled Botticelli Between Art History and Connoisseurship. This is comprised of essays on several scholars from what might justly be called the Golden Age of Botticelli studies: Crowe and Cavalcaselle by Donata Levi (who is somehow missing from the list of contributors), Aby Warburg by Claudia Wedepohl, Yukio Yashiro by Jonathan Nelson, and Jacques Mesnil, who is treated in a moving essay by Michel Hochman.

Individually and as a group, the essays are beyond reproach, models of subtle and sympathetic analysis. I would single out for special praise Wedepohl’s essay, based on a thorough knowledge of the Warburg Institute Archives, which takes the first steps in restoring the importance of Warburg’s psychologically founded aesthetics, based in empathy theory, which Gombrich considered a failure. She also rightly underscores the originality and significance of Warburg’s philological method in analysing the poetic foundation to Botticelli’s Primavera and Birth of Venus, which Gombrich considered a “fruitful mistake” in that it laid the foundation for the modern study of iconology.

Birth of Venus is often said to be the first full-scale representation of the nude goddess of love since antiquity

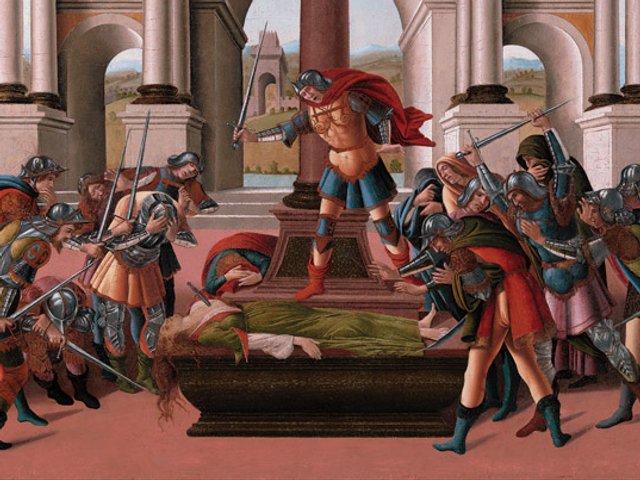

Botticelli’s Venus in the Primavera is fully clothed, but nonetheless appears as the spirit animating the fecundity of the season of spring. His Birth of Venus is often said to be the first full-scale representation of the nude goddess of love since antiquity, and indeed her pose and actions depend upon ancient descriptions of the foam-born Venus Anadyomene as painted by Apelles. And this raises the subject of sex, touched on in the second part.

There can be no doubt, as Francesco Ventrella argues in his essay, that “the Botticelli consumed by popular culture [of fin-de-siècle Europe] was not separate from the Botticelli art historians and connoisseurs were trying to identify.” He cites Walter Pater’s friend and disciple in English aesthetic circles, Vernon Lee (Violet Paget), who described the undeniably ephebic angels in the Madonna of the Pomegranate as “half-ravished”.

Art historians such as Ulmann and Warburg, Ventrella adds, sought “to purge Botticelli of the effeminate residues of aestheticism”. Anna Gruetzner Robins contributes an absorbing case study of sexualised aestheticism in the figures of the poet and dramatist Michael Field, the pen name of the lesbian couple Katherine Bradley and her niece Edith Cooper, who made something of a cult of Botticelli.

In the final group of essays, Botticelli Now, Georges Didi-Huberman submits an edited version of an essay originally published as Ninfa fluida. He takes as his point of departure Warburg’s figure of the erotically charged nymph, its basis in empathy theory and afterlife in Wilhelm Jensen’s novel Gradiva (the subject of a famous essay by Freud), expanding on this (as Stefan Weppelmann summarises it in his introduction) to a consideration of the “psychomorphic role of air and water as fluid substances with sexual connotations”.

This is followed by Riccardo Venturi’s excellent essay on Salvador Dalì’s Dream of Venus pavilion for the New York World’s Fair of 1939, in which Botticelli’s nude Venus is prominently cited, and the book ends with an essay by Gabriel Montua on Botticelli Referenced in the Works of Contemporary Artists to Address Issues of Gender and Global Politics.

There, in a nutshell, is the Post-Modernist agenda, capable of producing significant art, but an art that runs the risk, as the exhibition Botticelli Reimagined demonstrated, of reducing Botticelli to a slogan, or, as in the work of David LaChapelle, to soft porn thinly veiled as a political statement.

• Ana Debenedetti and Caroline Elam, eds. Botticelli Past and Present, UCL Press, 340pp, £50 (hb), £27.99 (pb)

Charles Dempsey is Professor Emeritus of the History of Italian Renaissance and Baroque Art at Johns Hopkins University