The lawsuits brought against the appropriation artist Richard Prince by the photographers Donald Graham and Eric McNatt—over Prince's use of their Instagram posts as the basis for works in his New Portraits series—have concluded with a pair of judgments on 25 January ordering the defendants to pay Graham and McNatt $650,000 in damages and $250,000 to cover their legal costs.

Besides Prince, the other defendants in the cases were the galleries where the works had been exhibited—Gagosian in the Graham case and Blum & Poe in the McNatt case (dealer Larry Gagosian was also a defendant in the Graham case). Trials for both cases were scheduled to take place within the next month—McNatt’s to begin on 29 January, while Graham’s was scheduled for 20 February, both in Manhattan. The judgments in favour of the plaintiffs effectively bring the decade-long legal fracas to an end.

Richard Prince has tested the bounds of copyright law Keystone/Gian Ehrenzeller; Associated Press/Alamy Stock Photo

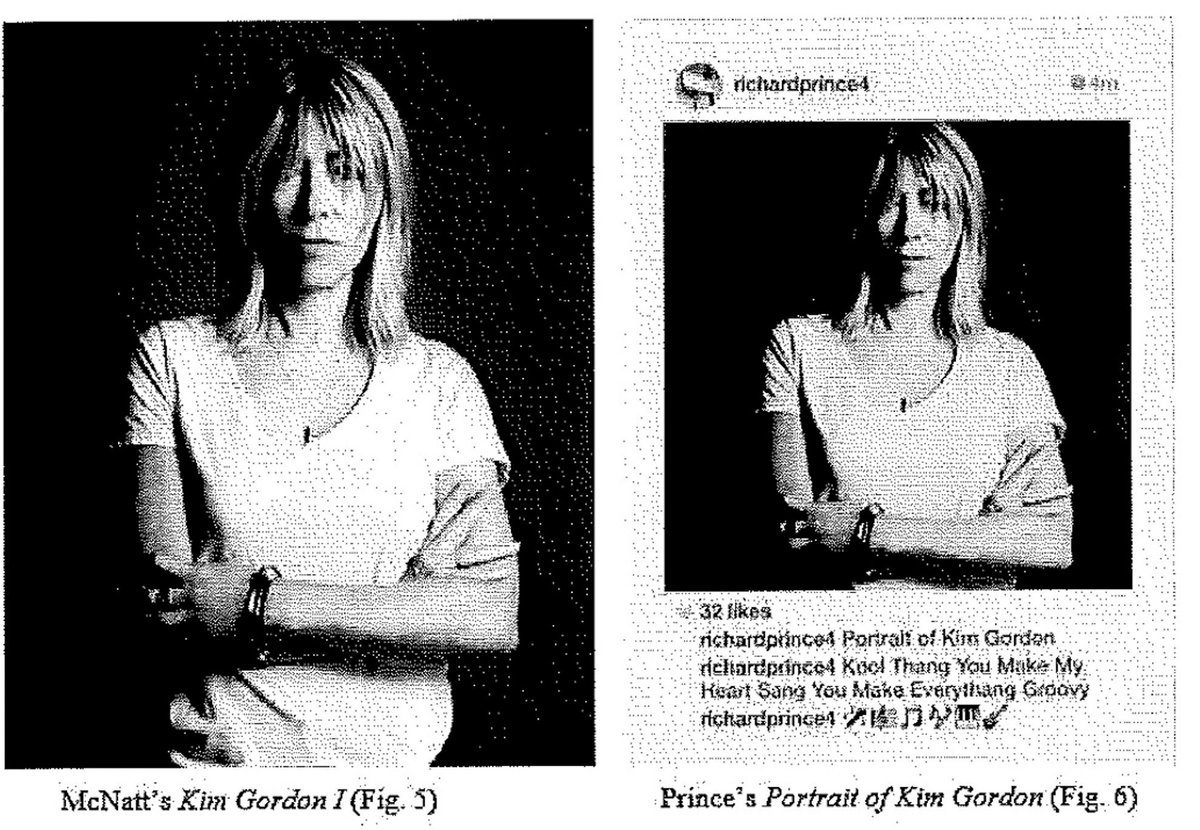

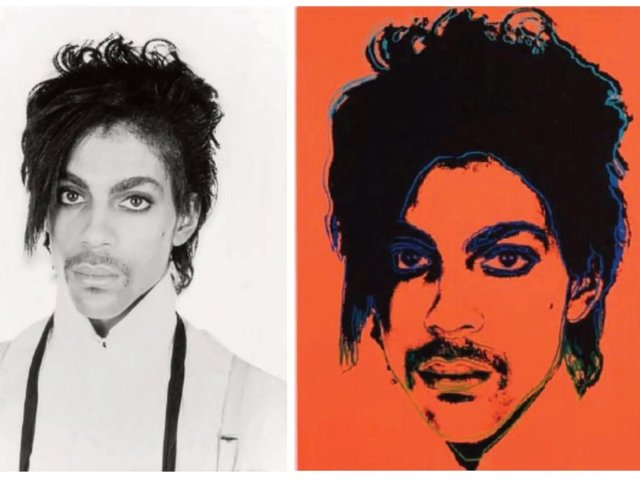

For his New Portraits series Prince, famed for his artistic appropriations, used screenshots of images posted by photographers on Instagram—including Graham’s picture of a Rastafarian man and McNatt’s photograph of Kim Gordon—that he enlarged and printed on canvases, adding his own commentary to both as if he had done so on Instagram. The series had its debut at Gagosian’s Madison Avenue gallery in autumn 2014.

The gallery reportedly sold works from the series for prices between $40,000 and $100,000. The photographers both sued Prince for copyright infringement (Graham in late 2015, McNatt in the autumn of 2016), charges the artist had denied, claiming that his treatment of their images were examples of fair use and thus exceptions to the federal copyright law.

In a previous response to McNatt’s lawsuit, Prince had stated that his “purpose was not to merely reproduce the image present in each of the New Portraits; rather, it was to satirise and provide commentary on the manner in which people today communicate, present themselves and relate to one another through social media”.

Fair-use factors

Under US copyright law, there are four factors that determine if fair use is a legitimate defence: the first relates to the purpose and character of the use, such as for commentary, criticism, news reporting and scholarly reports; the second involves the nature of the copyrighted work (whether it is factual, such as a biography, or fictional); the third is the amount of the copyrighted work that is used (whether it is, for instance, a sentence from a book or an entire chapter) and fourth, the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work. Rebecca Tushnet, a First Amendment scholar at Harvard Law School, notes that the fourth factor might work in Prince’s favour, stating that “there also may not be any interference with the market for Instagram pictures”.

A photo by Donald Graham (left) and a corresponding work from Richard Prince's New Portraits series (right) Court documents

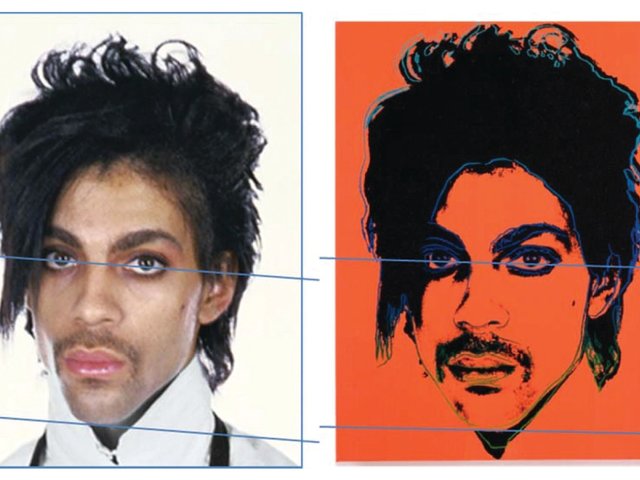

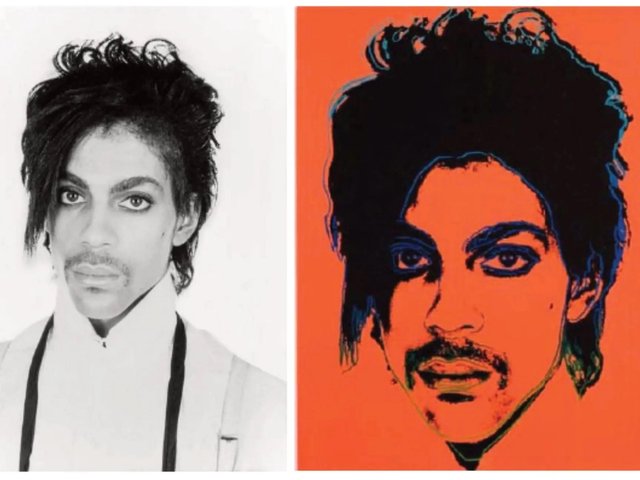

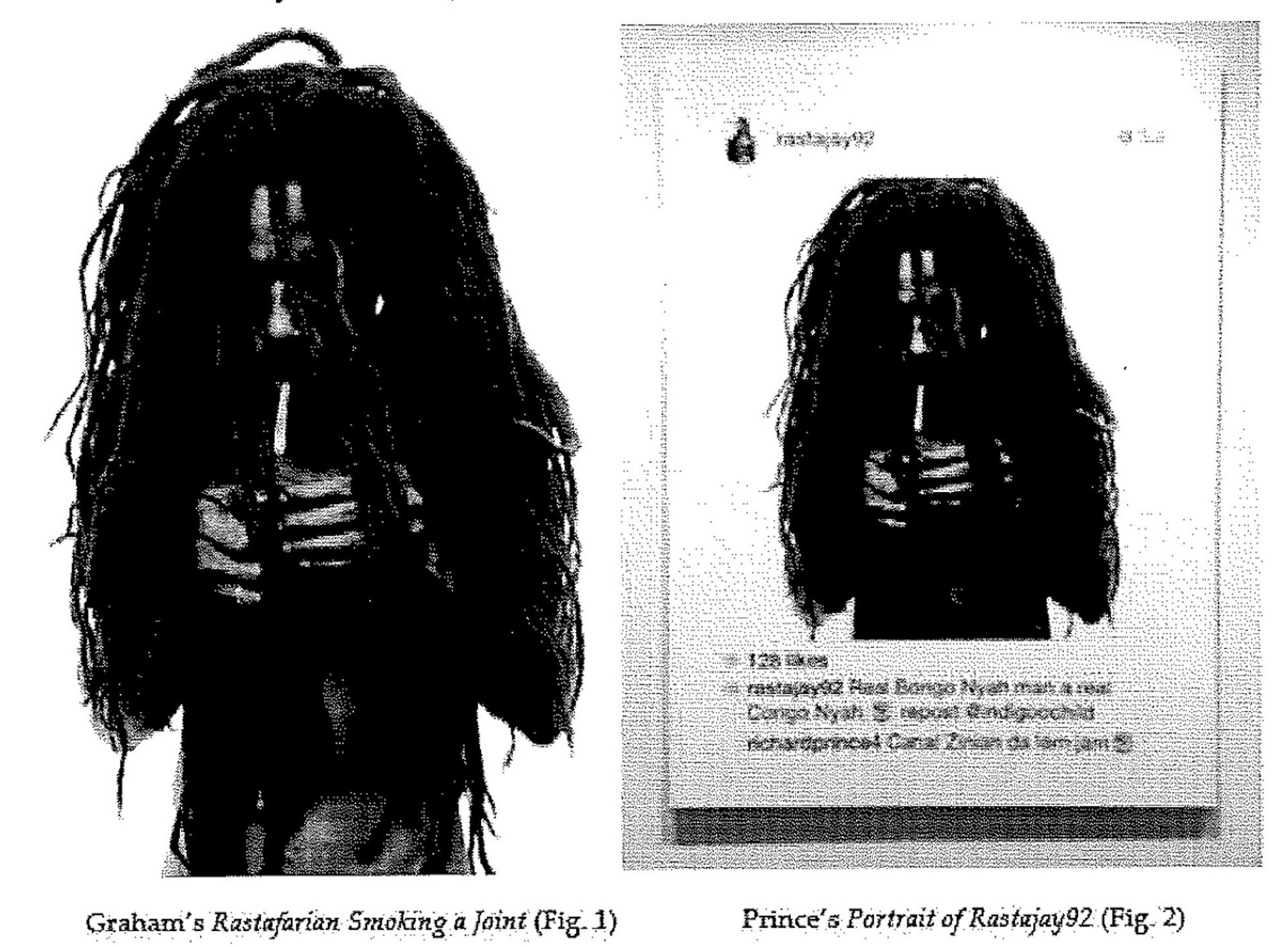

For years, artists have been seeking clarity from the courts about when and in what manner it is acceptable to use copyrighted imagery in their work, and it was hoped that the US Supreme Court might resolve the matter when it weighed in on the issue last May. Unfortunately for those seeking firm guidelines, there was no help. In that case, the Andy Warhol Foundation had sued the photographer Lynn Goldsmith—who had taken a picture of the musician Prince in 1981 for Newsweek that was the basis for Andy Warhol’s painted image of the recording artist for an article in Vanity Fair magazine in 1984—seeking a declaratory judgment that Warhol’s work did not infringe Goldsmith’s copyright.

The two images have clear similarities and differences, and the Warhol Foundation’s lawyers claimed that Warhol, who died in 1987, had so transformed the photographic portrait that it had become a new and original work worthy of its own copyright protection. By a seven-to-two majority, the Supreme Court disagreed, ruling in favour of Goldsmith and claiming that the “purpose and character of” Warhol’s use of Goldsmith’s photograph were identical—portraits for magazine articles about the performer—and that Warhol’s infringement of the photographer’s work had adversely affected her potential licensing income for her image.

Warhol later produced an edition of 15 silkscreen prints of that image, called the Prince Series, which were displayed in exhibitions. There was no ruling by the court on whether or not that series violated Goldsmith’s copyright, although the decision suggested that they would not have done so, because Goldsmith’s photograph and Warhol’s prints were directed at different audiences and markets. The Supreme Court’s ruling did not actually compare Goldsmith’s photograph with Warhol’s silkscreens, ignoring the question of whether or not the secondary work Warhol had created was transformative.

“The Supreme Court was not called upon to decide whether the display or sale of Warhol’s physical artwork itself infringed Goldsmith’s photograph,” says Amelia K. Brankov, a lawyer in New York who specialises in art and intellectual property cases. “The takeaway lesson from the Supreme Court’s decision is that the fair use analysis depends significantly on the nature of the follow-on usage of the artwork—is the use in question for commercial licensing? Or is it for non-profit publication or museum exhibition?”

New meanings and messages

The lawsuits against Richard Prince had been expected to involve more of a side-by-side analysis of imagery, perhaps raising fundamental questions about the legality of appropriation art and offering guidance for artists. Megan E. Noh, a partner in the New York law firm Pryor Cashman, says that in both cases the jury would "no doubt also be instructed to assess the so-called ‘transformativeness’ of Prince’s actual New Portraits series works, including their new meaning or message as compared to McNatt’s and Graham’s photographs”.

How does the context change meaning? How much change is required to transform one image into something else? “Basically, it’s a mess for juries and judges to figure out,” Tushnet says. She notes that artists like Prince and others who have found themselves in the same situation will need to articulate in court why they used a particular copyrighted image in their work, identifying what was exemplary, useful or important about it for their artistic goal. If they are not fully able to put their goals into words, they may find the courts unsympathetic.

The need for artists to check with a lawyer first may seem an unwelcome intrusion into the creative process, but Brankov says that the costs of defending against a claim of copyright infringement can be so high that it makes sense to consult an attorney before exhibiting a new work with appropriated material. Many artists “try to negotiate permissions/licenses in advance, reasoning that even if they might win a court case if the usage was challenged, they would rather avoid the risk entirely by dealing with the issue upfront”.