In a case that pitted an artist’s foundation against a photographer who copyrighted her work, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled today (18 May) that to avoid copyright infringement, a second artist who bases a new work on an earlier one must have a compelling justification to use the first image where the two works have a highly similar commercial use.

The decision ends the dispute over whether the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts (AWF) violated the copyright held by renowned celebrity photographer Lynn Goldsmith when it licensed an image that Warhol created based on Goldsmith’s portrait of the musician Prince. The foundation’s 2016 license to Condé Nast, to be used as an illustration for an article about Prince following his death, occurred years after Goldsmith granted a one-time use license to Vanity Fair to use her portrait as an artist’s reference for an illustration for a 1984 article, also about Prince.

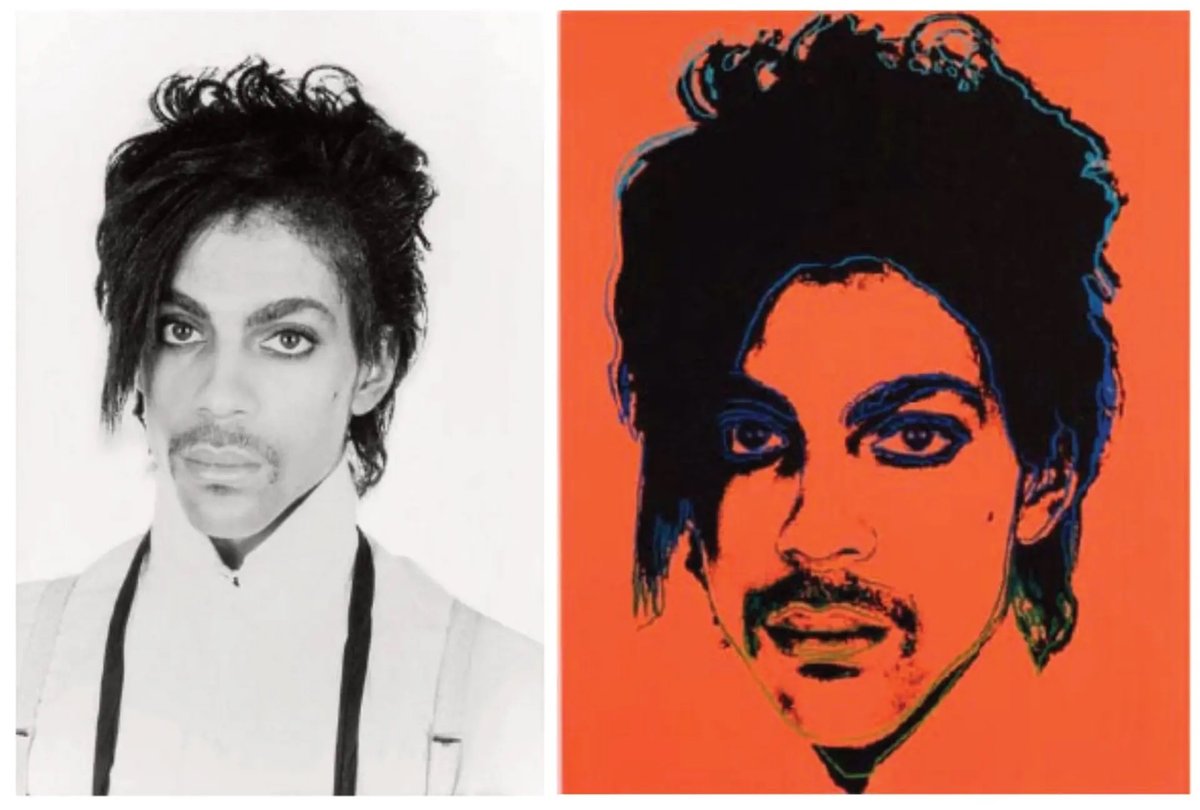

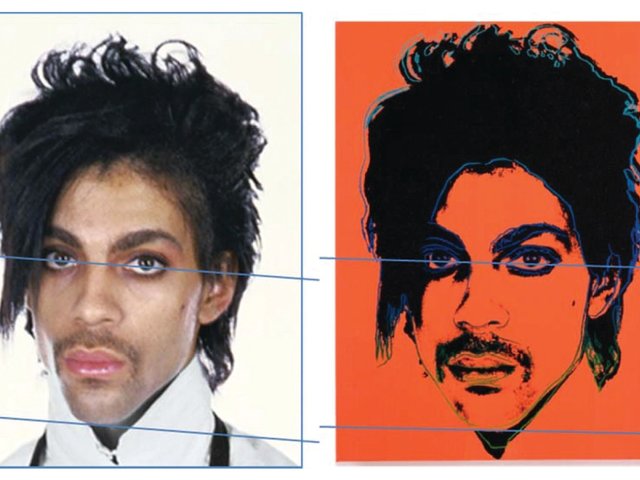

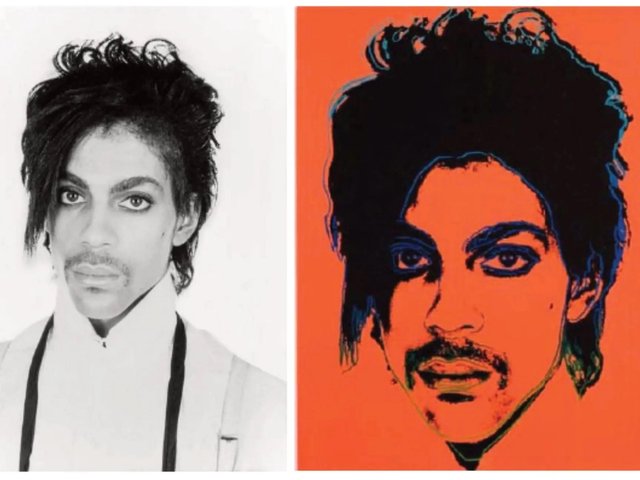

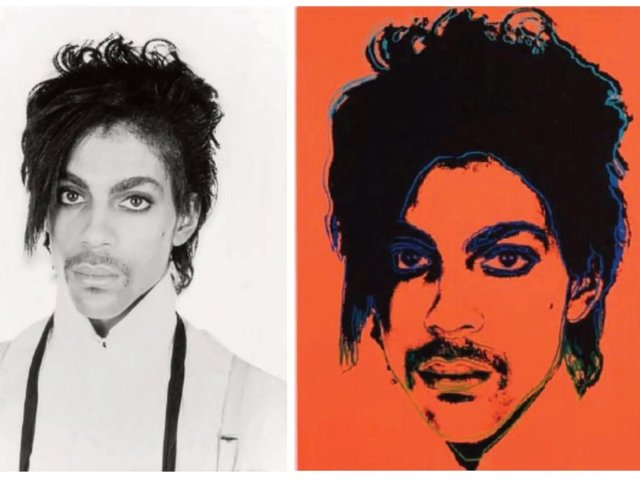

Under Goldsmith’s earlier license to Vanity Fair, Warhol created the Prince Series, a number of works based on her photograph, including a purple portrait of Prince (Purple Prince) that appeared with the Vanity Fair article. Goldsmith learned of the Prince Series in 2016, when she saw Warhol’s orange portrait of Prince (Orange Prince) on the Condé Nast magazine cover.

The case gained wide attention because of its implications for potentially lost licensing revenues to creators like photographers who license their works, and to artists who appropriate or re-work existing ones.

The court’s 7-2 opinion, written by Justice Sonya Sotomayor, echoed concerns raised by both the US government and some justices during oral arguments in the case in October 2022, pointing to the very similar commercial use—illustrating a magazine article about Prince—to which both images were put.

In the lawsuit, AWF asserted copyright in the Prince Series and asked the Court to overturn the Second Circuit appeals court’s denial of its copyright claim. Warhol had sufficiently changed the “meaning or message” of Goldsmith’s image to earn his works fair use protection as “transformative” under US copyright law, AWF said, but the appeals court wrongly discounted considering any “changed meaning or message” in evaluating transformativeness. But rather than reverse the decision below, the Court affirmed it, adding clarification about the extent and kind of transformation that is needed to protect secondary works as non-infringing fair use.

The Court said that in applying the transformativeness test—the sole fair use test at issue in the appeal, and the first of four fair use factors spelled out under the federal copyright statute—the question is whether the secondary use “has a further purpose or different character, which is a matter of degree, and the degree of difference must be balanced against the commercial nature of the use”. If the two works “share the same or highly similar purposes, and the second use is of a commercial nature”, the transformativeness test is likely to weigh against fair use, “absent some other justification for copying”. The lower court found that AWF failed on all four fair use tests, so the Court’s ruling leaves the overall fair use evaluation unchanged.

The Court limited its analysis to AWF’s specific commercial licensing to Condé Nast of Orange Prince, one of the Prince Series images, and said that the purpose of Orange Prince was substantially the same as that of Goldsmith’s original. “Both are portraits of Prince used in magazines to illustrate stories about Prince,” the court’s opinion states. AWF’s use was also of a commercial nature, and taken together, the two elements “counsel against fair use here”.

The Court said that it saw an “intractable problem” in AWF’s reliance on a “meaning or message” test: while prior Supreme Court decisions had referenced new “meaning or message” in considering transformativeness, this does not mean that copyright law favours any use that adds new meaning or message. “Because AWF’s commercial use of Goldsmith’s photograph to illustrate a magazine about Prince is so similar to the photograph’s typical use, a particularly compelling justification is needed” for the copying. “Yet AWF offers no independent justification, let alone a compelling one” other than to convey a new meaning or message, and “that alone is not enough for the first factor to favour fair use”.

The majority disagreed with a point made in Justice Elena Kagan’s dissent that restrictions on copying can inhibit follow-on works. “It will not impoverish our word to require AWF to pay Goldsmith a fraction of the proceeds from its reuse of her copyrighted work,” the majority wrote. Chief Justice John Roberts joined Kagan in the dissent.

In a statement, Goldsmith said that she was “thrilled by today’s decision and thankful to the Court for hearing our side of the story. This is a great day for photographers and other artists who make a living by licensing their art.”

Joel Wachs, president of the AWF, said in a statement that the foundation “respectfully disagree[s] with the Court’s ruling that the 2016 licensing of Orange Prince was not protected by the fair use doctrine. At the same time, we welcome the Court’s clarification that its decision is limited to that single licensing and does not question the legality of Andy Warhol’s creation of the Prince Series in 1984. Going forward, we will continue standing up for the rights of artists to create transformative works under the Copyright Act and the First Amendment.”