The long court dispute over the use by the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts (AWF) of a copyrighted portrait has ended, with the foundation agreeing to pay the celebrity photographer Lynn Goldsmith for its unlicensed 2016 use of her portrait of the rock musician Prince.

On Monday (18 March), the New York federal district court in Manhattan entered judgment in favour of Goldsmith on her copyright infringement counterclaim against the foundation, awarding her $10,250 in damages and lost profits and almost $11,273 in court costs. The action follows a joint motion filed by the parties on 15 March asking the court to enter their proposed judgment and close the case.

The parties thus resolved Goldsmith’s outstanding money claim, which was left unsettled by a landmark US Supreme Court decision in May 2023 rejecting the Warhol Foundation’s argument that it owed Goldsmith nothing. The AWF had argued that when Warhol created a portrait of Prince in 1984, based on Goldsmith’s license to Vanity Fair magazine to use her portrait as an artist’s reference, he had so changed its “meaning or message” that his version was protected under the fair use doctrine. The case sparked an art world uproar over whether an alleged change in an original work’s “meaning or message” can protect a secondary work from an infringement claim. The Supreme Court said it could not.

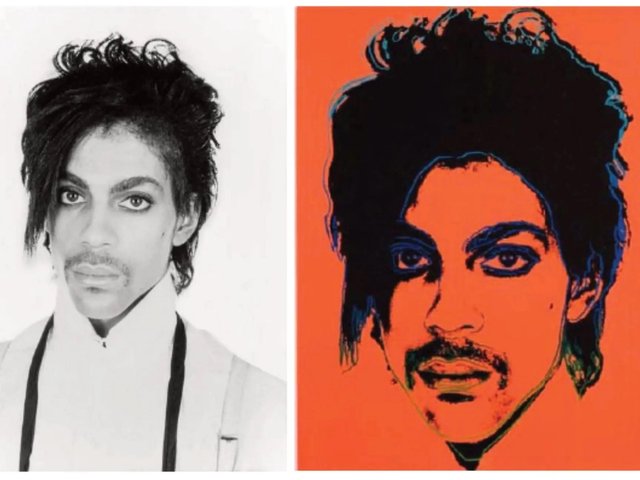

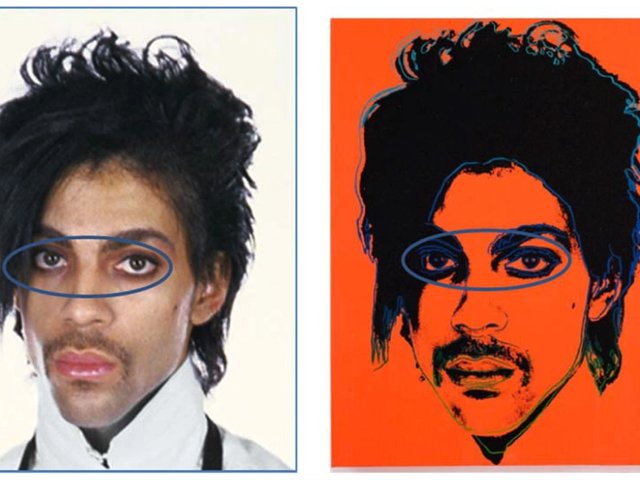

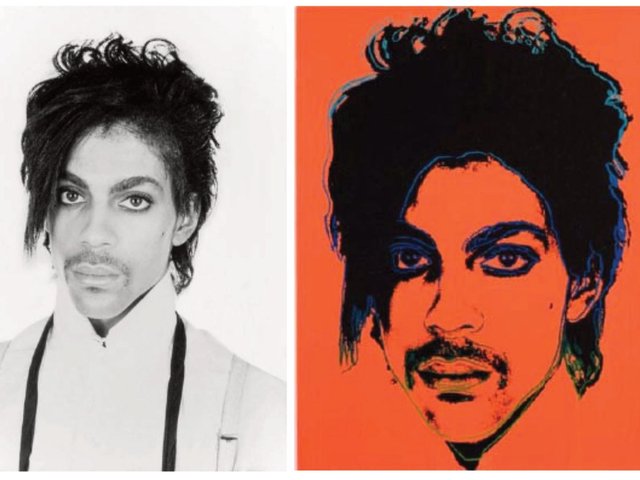

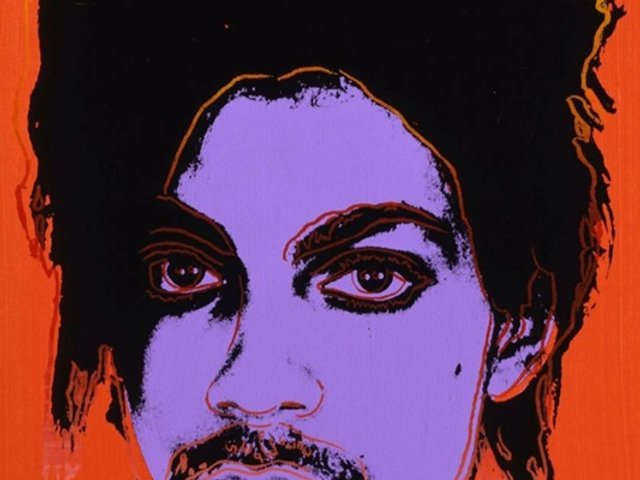

In 1984, for $400, Goldsmith granted a one-time license to Vanity Fair magazine to use her studio portrait of Prince as an artist’s reference for an illustration to accompany an article about the musician. She had not known that the magazine hired Warhol to create the orange illustration it published, or that he created 15 additional images based on her portrait, later called the Prince Series. In 2016, Warhol’s purple portrait of Prince, licensed by the foundation to Vanity Fair parent Condé Nast for a fee of $10,250, appeared on a Condé Nast magazine cover. After Goldsmith told the AWF that she believed it had infringed her copyright, the foundation sued her, seeking a judgment that it held copyright to the Prince Series because Warhol’s changes were transformative enough to constitute fair use.

In the Supreme Court appeal, the photographer argued that: “Fair use does not allow AWF to sell for $10,250 a materially identical image to the same publisher without paying or crediting Goldsmith.” The court agreed, saying: “It will not impoverish our world to require AWF to pay Goldsmith a fraction of the proceeds from its reuse of her copyrighted work.” Such payments “are incentives for artists to create original works in the first place”.

This month’s judgment hands Goldsmith her fee, matching what AWF got in 2016 from its license to Condé Nast. The judgment adds that to the extent Goldsmith had advanced any claims for relief as to the creation of the Prince Series, she is no longer doing so because the statute of limitations has expired. In view of that, the judgment dismissed AWF’s claim to copyright in the Prince Series, without prejudice.

In response to the judgment, Goldsmith tells The Art Newspaper: “I am pleased that this lawsuit, which was filed against me in 2017, has concluded with a copyright-infringement judgment that protects the rights to my original creation, a black-and-white photograph made in my photo studio of Prince. The Supreme Court’s 2023 fair use ruling in my favour is crucially important because it affirms the rights of photographers and other creators. I am proud to have fought this successful fight on their behalf.”

A spokesperson for Latham & Watkins, the law firm representing the AWF in this matter, tells The Art Newspaper: “The Warhol Foundation brought this case as part of its mission of supporting artistic free expression and celebrating Andy Warhol’s legacy. The Supreme Court ruled narrowly in Ms. Goldsmith’s favour, addressing only the Foundation’s 2016 licensing of a single Prince portrait. The Foundation respectfully disagrees with that decision. Given that Ms. Goldsmith has now withdrawn any claim that Andy Warhol violated her copyrights when he created the Prince Series in 1984, the Foundation is happy to put this litigation to rest and move forward with its work supporting up-and-coming artists.”