In Vanessa Engle’s 1996 documentary, Two Melons and a Stinking Fish, the UK artist Sarah Lucas buys half-a-dozen organic eggs from a butcher’s shop in Highbury, north London, for £1.24. She later fries up two, and places them onto a varnished wooden table alongside a doner kebab—a pitta bulging with strips of rotisserie meat. The foodstuffs were arranged by the artist to evoke the shape of a woman’s breasts and genitals. Written on the table in black pen are the credits for the work: “Two fried eggs and a kebab, 1992, Sarah Lucas”. The title echoes the kind of vulgar banter about women’s bodies the artist remembers hearing while growing up in London, and she once referred to the work as a “defence mechanism”, saying she had “live[d] with remarks like that all my life”.

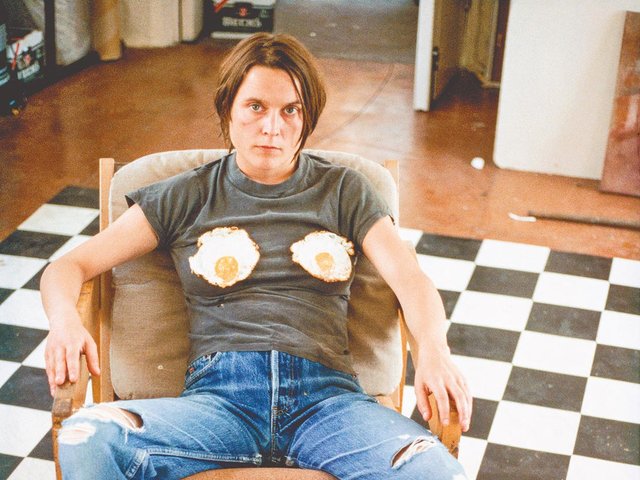

Lucas has spent a lot of time with eggs in her work. Perhaps the most famous is her Self Portrait with Fried Eggs (1996). This photo shows the artist sitting deep in a chair, her back straight, her denim-clad legs open at an acute angle and her gaze direct and unflinching. Two fried eggs have been gingerly placed on her khaki green T-shirt over her breasts, the yolks pointing in different directions. Of her ability to serve up provocation and humour at once, the art critic Roberta Smith once wrote, “Over the years, I don’t think any artist’s work has shocked me—mostly in good ways—as often as Ms Lucas’s.”

Rigid parameters

Since a significant number of women’s bodies produce eggs on a regular basis, it’s not surprising to see them show up in feminist art, often as a visual eponym for the female body itself, and to explore everything from sexism and eroticism to themes of oppression and liberation. In 1967, the Brazilian artist Lygia Pape hatched out of a white box onto a beach in her video, O Ovo (the egg). Readable as a comment on the rigid parameters of the art world, this escape from inside a white, oppressive cube into an organic natural scene was a prescient comment on the types of gallery spaces that would grow to ubiquity in the Western world—spaces in which women artists would be regularly under-represented.

The indoors—the home in particular—is a recurring theme in feminist art featuring eggs

The indoors—the home in particular—is a recurring theme in feminist art featuring eggs, including the work of the British artist Su Richardson. Her textile piece, Burnt Breakfast (1975–77), a crocheted plate of egg, sausage, bacon and tomato, was done as part of the Postal Art Event, a project intended to connect women artists across the UK through the sharing of mail art. Alongside postcards and other items, this full English breakfast eventually found its way through the letterbox of one of Richardson’s contemporaries, and hints at the fact that a lot of the women artists that she knew, especially mothers with young children, worked from home rather than at a studio.

The feminist pioneer and consummate collaborator Judy Chicago also explores domestic themes. In 1971, she and Miriam Schapiro co-founded the Feminist Art Program at the California Institute of the Arts, and started work on what would become 1972’s groundbreaking Womanhouse, a multi-participant, multimedia installation set in a run-down Hollywood mansion. One of the big attractions was the walk-in installation by Susan Frazier, Vicki Hodgetts and Robin Weltsch, designed to mimic a carefully organised, modern Western kitchen. All the items and surfaces in Nurturant Kitchen were sickly Pepto Bismol pink, from the space-age gadgets to the stove and pantry items.

New iterations increasingly resembled breasts, the yolks eventually morphing into nipples

Foam fried-egg formations covered the ceiling and crept down the walls, growing pinker and pinker as they sunk; new iterations increasingly resembled breasts, the yolks eventually morphing into nipples. Camp and surreal, the installation hinted at the pressures put on women to be human dolls: to play house (cook eggs) and be sexually available on demand (show breasts).

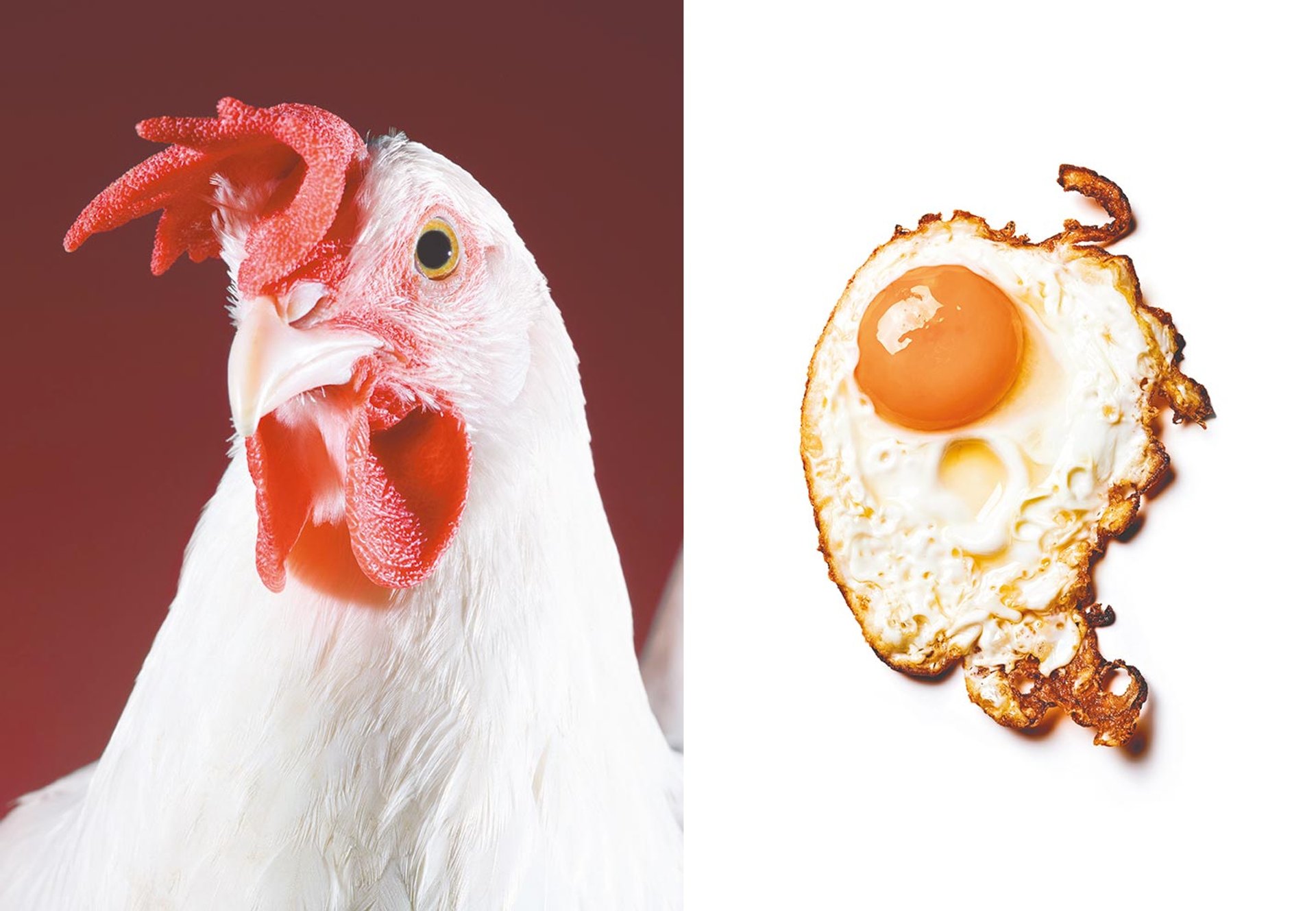

Which came first? Marius W. Hansen’s Chicken (2021), left, or Bobby Doherty cover image for The Gourmand’s Egg Photos: Marius W. Hansen and Bobby Doherty

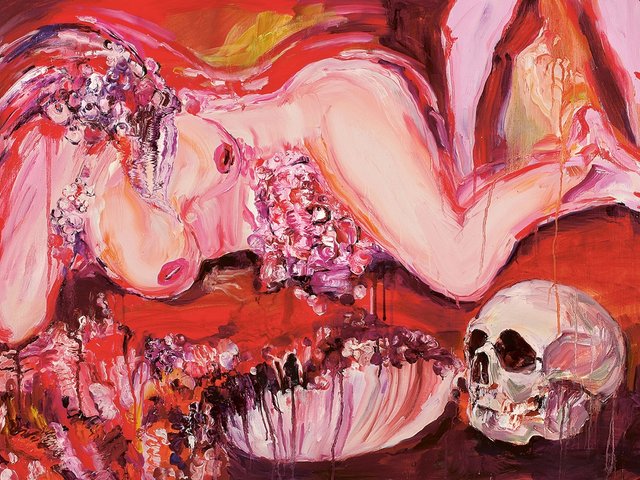

Ablutions (1972) was a much more difficult work by Chicago and her collaborators, in this instance Suzanne Lacy, Sandra Orgel and Aviva Rahmani. The performance was about rape, and featured two women sitting in metal wash tubs filled with eggs, blood and clay. Another woman is bound from head to toe with gauze bandages. Scattered around the performers are broken eggshells, ropes, chains and animal kidneys. A pre-recorded soundtrack played in the room, testimonials spoken by women about their experiences of sexual violence. Chicago then returned to the symbolic power of eggs in the 1980s with her Birth Project, a collaborative series of multimedia works, including the embroidery Hatching the Universal Egg E3 (1984). Done with the needleworker Kris Wetterlund, the expressive piece features a symbolic figure holding a giant cracking egg; she is both the universal mother and an individual woman giving birth.

Flipping expectations about what type of anatomy an egg could embody, the Austrian avant-gardist Renate Bertlmann’s Exhibitionism (1973) was an elegant but still bawdy sculptural optical illusion about masculinity. Comprising three abstract mixed-media assemblages, it featured delicate lines, careful shading and two egg-shaped Styrofoam objects. A closer look reveals the outline of legs, bums and testicles seen from various angles. Bertlmann says the idea for the piece came to her after hearing about “militant feminists who wanted to cut off [men’s] balls”. Instead, she chose to present the male as an object of “sexual disrobement and denudation”. This approach seems to have been effective. One gallerist refused to include the work in a show because it made him feel like he was “exposing himself”.

Unapologetic carnality

Marilyn Minter offered a similarly zoomed anatomical view when she cast her critical eye on the world of commercial image production for Quail’s Egg (2004). One of the US artist’s hyperreal enamel-on-metal paintings, it shows a close-up of a woman’s glossy red, slightly parted lips.

Marilyn Minter’s Quail’s Egg (2004) © Marilyn Minter; courtesy of LGDR

She is crushing a small, brown-spotted quail’s egg with her perfectly white teeth, while golden yolk dribbles down the side of her mouth. Intended as a provocation about the male gaze, it is also a presentation of unapologetic female carnality. What at first might seem like the usual type of objectified body-part imagery used to sell goods quickly shifts into the beautiful and the grotesque, and back again.

Recent feminist art continues to harness the symbolic power of the egg. In 2018, the British artist Heather Phillipson’s cartoonish my name is lettie eggsyrub was installed at London’s Gloucester Road Tube station to mark 100 years of women’s suffrage in the UK. The installation included screens showing eggs being cracked, whipped and spread across sandwiches. It was reported that this stirred the hunger of some commuters, a fact that surprised Phillipson, who is vegan. Not only do the eggs represent fertility, strength, birth and futurity, she said, but also the other side of the coin: “(over)production, consumption, exploitation and fragility.”

• This is an excerpt from The Gourmand’s Egg: A Collection of Stories and Recipes (2022), published by Taschen