Among South Korea’s many lauded cultural exports, the resonating strength of its feminist art, as a beacon for other Asia art scenes, attracts insufficient credit from art-world commentators, whether within Korea or beyond. And even as artists like Lee Bul and Haegue Yang have become market favourites, their feminist origins are reduced to footnotes. The societal battles that forged the country’s feminist movement now rage hotter than ever. Yet “K-feminism” and its art receive little of the official backing that pop music and drama enjoy, while the complex, diverse long-history of Korean feminist art eschews simplistic packaging.

Some official support, though, was forthcoming for Kim Hong-hee’s Korean Feminist Artists: Construct and Deconstruct. This new book recentres Korean feminist art through an encyclopaedic overview that puts the focus firmly on the artists. Kim Hong-hee, the artistic director of the 2006 Gwangju Biennale and then the director of the Seoul Museum of Art from 2012 to 2016, examines 42 artists through 15 conceptual sections, within which are essays including a contribution by the feminist poet Kim Hyesoon, individual histories and more. All but one of these artists were still living at the time of writing, and Kim Hong-hee usually pairs representatives from different generations, as a way of tracking how ideas have developed over time.

While the writing can be tryingly academic in parts, the translation in the main flows well, and from the dry obtusity some pith pops out. Kim Hong-hee describes the “narcissistic pitfalls of essential feminism” in her critique of early waves of Korean feminist art, dispatching notions of “girl power” and maternal romanticism as expediently as she overviews chronologies and contexts in her quick opening chapters. She slaps that label, “naïve essentialism”, on the Pyohyeon (Expression) Group of the early 1970s, which is where she begins her history. Kim considers Pyohyeon—not Korea’s 1960s early Silheommisul avant-garde—as the first “rebellion against Modernism”. The group included artists such as Yoo Yonghee and celebrated that essentialised “womanhood” as part of a heavily censored navigation through topics like dictatorship, resistance and identity in Korea.

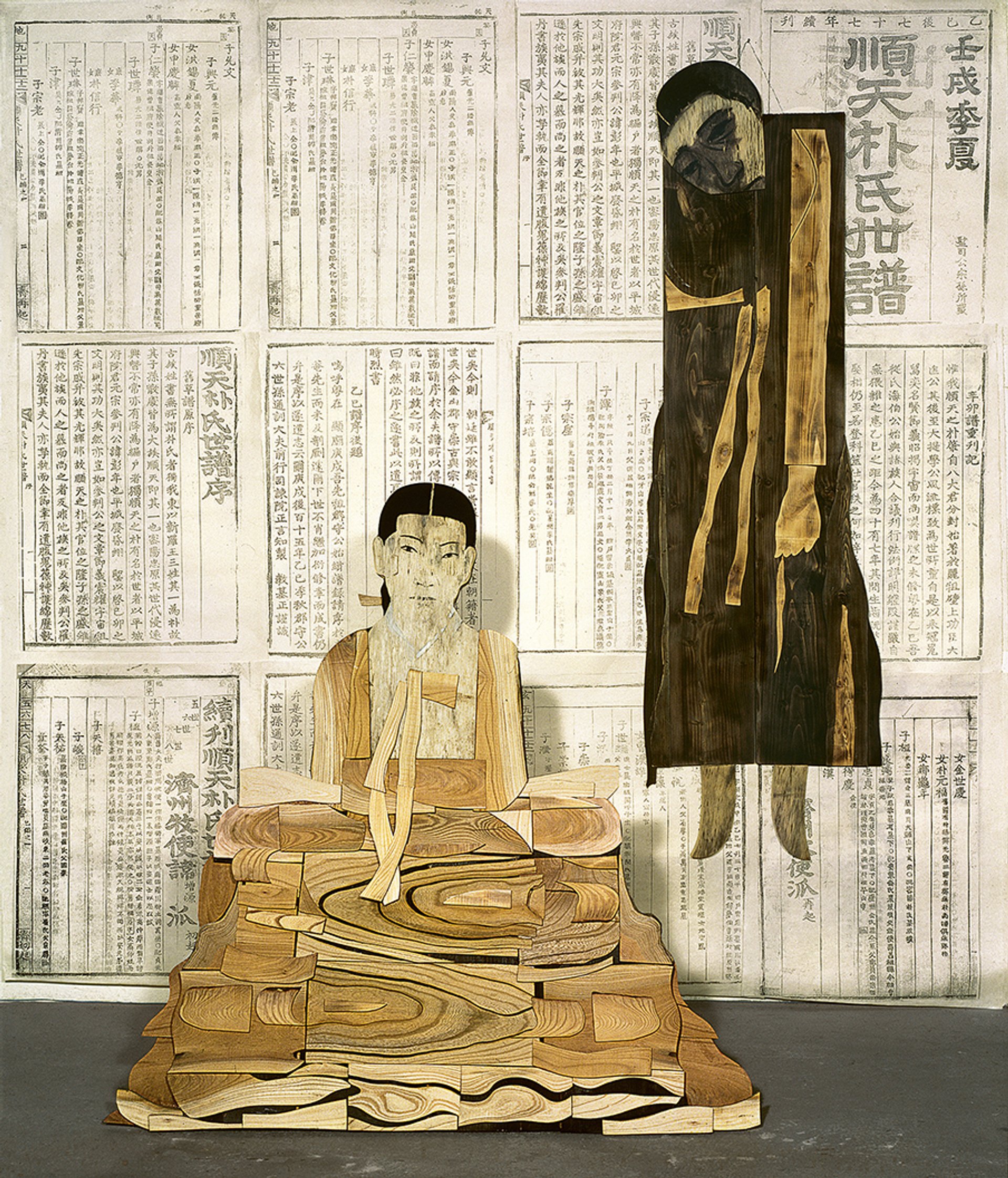

As Korea inched and lurched towards democracy in the mid-1980s, another movement called Yeoseongmisal or Yeoseongmijeon, meaning “Korean women”, emerged around artists like Yun Suknam and Kim Insoon bluntly exploring female experiences. It was a partner and parallel to the larger activist Minjoong or people’s art movement.

Yun Suknam’s Genealogy (1993) Courtesy of the artist

The inflection point, the show to know for feminist contemporary art in Korea, was The Patjis on Parade exhibition in 1999 at the Seoul Arts Centre. Patji in Korean means a “bad” woman who is selfish or rebellious, deriving from the stepsister characters in Korea’s traditional version of Cinderella. The women artists reclaimed the pejorative, in a show split between archival and contemporary sections.

Kim Hong-hee directed the planning committee for Patjis, and in 1994 she curated Woman, The Difference and Power at Hankuk Art Museum. Even so, she avoids her own role and reminiscences, offering an aloof presentation of events; this is no memoir, though her tales would also make for an incredible read. Here, instead, they are efficient table-setting before chewing into the artists and the sub-themes, with each chapter its own essay.

She starts with Yun Suknam paired with Jang Pa for “Femininity and Sexuality”, followed by the body art of Lee Bul, Fi Jae Lee and Mire Lee. Each artist’s presentation is carefully tied into her political and artistic environment, allowing 42 different jumps through recent Korean history via artistic lenses. In “Ecofeminisms”, we meet Hyunsook Hong Lee, who channels animals including lions and whales in her videos, and Eunji Cho, an “existential feminist”, who describes feminism as an act of survival. Cho’s videos and performances include playing music to comfort farmed-food animals and interviews with genocide survivors. Hong Lee, in her three-decade to-date career, has farmed perilla seeds and reimagined menopause as a superpower.

Exile, silencing, protest

Kim breaks down the apartness, so integral to Korean identity, into two chapters, one on wanderers and another on the diaspora. Nomadism focuses on the familiar figures of Kimsooja and Jyungah Ham, both of whom explore the broader globe in their works while rooted in feminine Korean traditions. It is followed by the “North American Diaspora Artists” of Yong Soon Min, Jin-me Yoon and Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, all of whom emigrated as children. Before her 1982 murder, Cha was part of the Northern Californian post-colonial and experimental activist scene of the 1970s, making striking video works about exile, silencing and protest. Min, also in California, watched closely the protests and massacres happening back in Korea during the late 1970s and early 1980s, and incorporated sharp critiques of American colonialisation of Korea and of Western constructs of Asia and Asianness. In 2002 and 2003, as America rushed into the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, Min (who died just before publication) channelled Yoko Ono and John Lennon with a bed, in Will **** for Peace.

For each artist and each section, Kim Hong-hee is meticulous about verifying details, plus supplying extensive footnotes and citations. Her all-embracing familiarity is apparent, and Korean Feminist Artists assembles her 30 years of research into a compelling, expansive document that is nevertheless a start, not a finish. Even after 360 pages, we are left wanting more of Korea’s Patjis. They certainly have plenty more to say.

• Lisa Movius is an arts writer based in Shanghai and the China bureau chief of The Art Newspaper

• Kim Hong-hee, with a contribution by Kim Hyesoon, Korean Feminist Artists: Confront and Deconstruct, Phaidon, 360pp, 260 colour illustrations, £59.95 (hb), published 17 October