So here's how it works: they check you out, you list your painting for sale on the site—anonymously—then a buyer—who is also anonymous—makes an offer for it. You do a deal—anonymously—then send your painting to be examined in a Delaware freeport. It is then shipped to the buyer—you still do not know who they are, nor they you—and you get the money in your account, minus a 10% charge. You will never know where that painting has gone, they will never know where it has come from.

And they say the art market is opaque...

It all sounds a bit cloak and dagger doesn't it? Well, the founders of LiveArt Market, the online, peer-to-peer trading platform, which has just soft launched, say it is anything but—and insist that anonymity and trust can go hand-in-hand.

The LiveArt site began limited, invitation-only trading last week and has so far made around $5m in sales, with over 1,000 contemporary works of art listed, worth around $120m in total. Prices range broadly from $50,000 to $500,000 with works by Amoako Boafo and Ed Clark already sold for six figure sums. Vendors can choose to list their works publicly or in private mode, with the the artist's name and an image of a similar work. And for any sale agreed, the transaction is handled through LiveArt's escrow account.

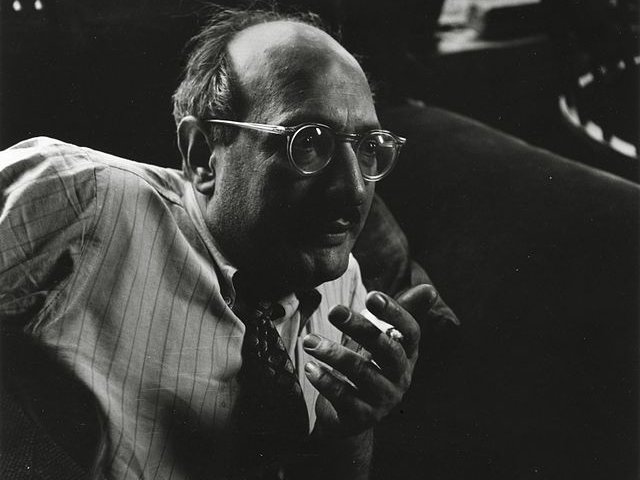

LiveArt Market is the brainchild of Adam Chinn, formerly chief operating officer at Sotheby's and more recently an advisor to the Mugrabi family (he is no longer working for them, he says, LiveArt being "my only day job at the moment"); John Auerbach, previously head of Sotheby's digital business, the Art & Objects Division, and jewellery, watches and wine; and the tech entrepreneur Boris Pevzner, founder of numerous online companies including Collectrium, a digital inventory management and art selling platform that was bought by Christie’s.

"Towards the end of 2019 I was talking to John Auerbach and said to him, the art world really needs a peer-to-peer selling platform. It's crazy that it doesn't exist," Chinn tells The Art Newspaper. "He said, funny you should mention that because I've been talking to Boris Pevzner about doing this. And, long story short, end of 2019 we started building this and spent Covid creating a business."

They started by buying the Live Auction Art app, "because it had 40,000 downloads and thought it a nifty way to get the eyeballs we needed for the marketplace," Chinn says. It also had the auction price data that is crucial to the development of LiveArt's AI estimating tool (they have since bought more sales data).

But how, when anti-money laundering laws now require sellers to know the identity of the ultimate buyer, can you keep both sides anonymous and not potentially facilitate laundering? By vetting both sides as the intermediary, says George O’Dell, LiveArt's executive vice president (also a former Sotheby's employee): "In terms of KYC [Know Your Customer], anti-money laundering and bank verification, the majority of us have spent time at various auction houses and saw very quickly the on-boarding of KYC and various anti-money laundering (AML) standards. So it made sense from the word go to stick to the same high standards. Any user has to provide their KYC documents—for a sole trader, that's their passport or driver's licence, mailing address and bank details." He adds: "You can't go onto LiveArt as a buyer and bid on something for $1m if you're only bank verified for $50,000."

Sellers can keep the details of their work private and can decide what information the buyer can see at any stage, in order to "prevent your work travelling round the internet and being offered back to you in five minutes," O'Dell says. Chinn stresses that the process is "blind" throughout: "The 'Deal Room' is mediated by a bot so if you say, 'hey what's your email?' to get around us, that won't work and will be blocked."

Adam Chinn Courtesy of LiveArt

The works are vetted too. "Everything has come through us to be authenticated too, you can't just upload whatever you like, it's independently vetted," says Marisa Kayyem, LiveArt's chief content and data officer. She adds the deal room allows "buyer and seller to know exactly who is getting paid what, which I know from my work as an advisor doesn't always happen."

And O'Dell adds: "What we don't want to have is an unknown Sunday painter uploading their own works without any backing, because that dilutes the quality."

However, there will be a primary offering from more established artists in time, Chinn says: "This is not eBay. But we're also not looking to compete with auction houses at the top end. Where we're looking to serve is the middle market, which is where all the profit is but we believe is very poorly served. If you have a $100,000 artwork we're delighted to take it and let you have control over the price. You will not be lot 352 in a 400-lot sale."

The seller, Chinn believes, is the most incentivised person to sell a work of art, "so if you give them the tools to reach a broad audience, and provide the back end through condition reports, escrow accounts and fulfilment, then you can successfully have more people trading directly with each other." He adds: "The entire process is decentralised until the very last minute, when a sale is agreed, the money is in escrow and the work comes to the Delaware warehouse. We're only incurring the cost when we know we've got revenue."

At the moment all works must travel to Delaware to be inspected and have a condition report carried out before going to the buyer (any transaction will be cancelled at this point if a work is found to be incorrect). But Chinn says as the business grows, they plan to have "similar fulfilment centres in freeports like Zurich or Geneva, and somewhere like Singapore."

There is one caveat to the anonymity pledge: if there is an issue after the transaction completes. Chinn says: "For legal purposes, if there is a legitimate beef, we will release the name of the seller and the buyer will have recourse against the seller."

While the LiveArt Estimate function is built on AI technology, "the algorithm is not just machine learning," Kayyem says. "We as art historians, data analysts, people who are aware of private sales, we feed in much more specific data to the algorithm as people who know who the art market works." She adds: "If there are not enough secondary market data points for a really emerging artist, we do not give LiveArt estimates. There have to be over ten secondary market data points."

The site currently has 22,000 monthly users, which Chinn says, "is pretty much the universe when it comes to selling art at $50,000 and above." He adds: "If you're a mid-level gallery or dealer who has a large secondary market inventory that you don't really have the reach to sell, and you don't want to have it hawked round by every runner in the business, this is a pretty cool solution for you."

Buyer's pay a 10% flat buyer's premium, sellers pay nothing—aside from shipping their works to the Delaware warehouse.

That 10% fee cannot provide a huge income for the LiveArt business, which has 30 employees, 22 of them working on the tech side alone. Given the data and valuation tools the platform has, might they branch out into the growing field of art loans for those wishing to use their art as leverage? "This has opened up a world of opportunity," says Chinn, who was heavily involved in the lending side of Sotheby's Financial Services. "Whether that's something we do ourselves or if we partner with someone else, anything is possible...we could have people come to us and say we'd love a connection to shipping, insuring, art lending, so there are lots of possibilities."