The art market is booming again, bigger than ever.

That was the message given to the world’s media after last month’s fortnight of marquee auctions at Christie’s, Sotheby’s and Phillips in New York.

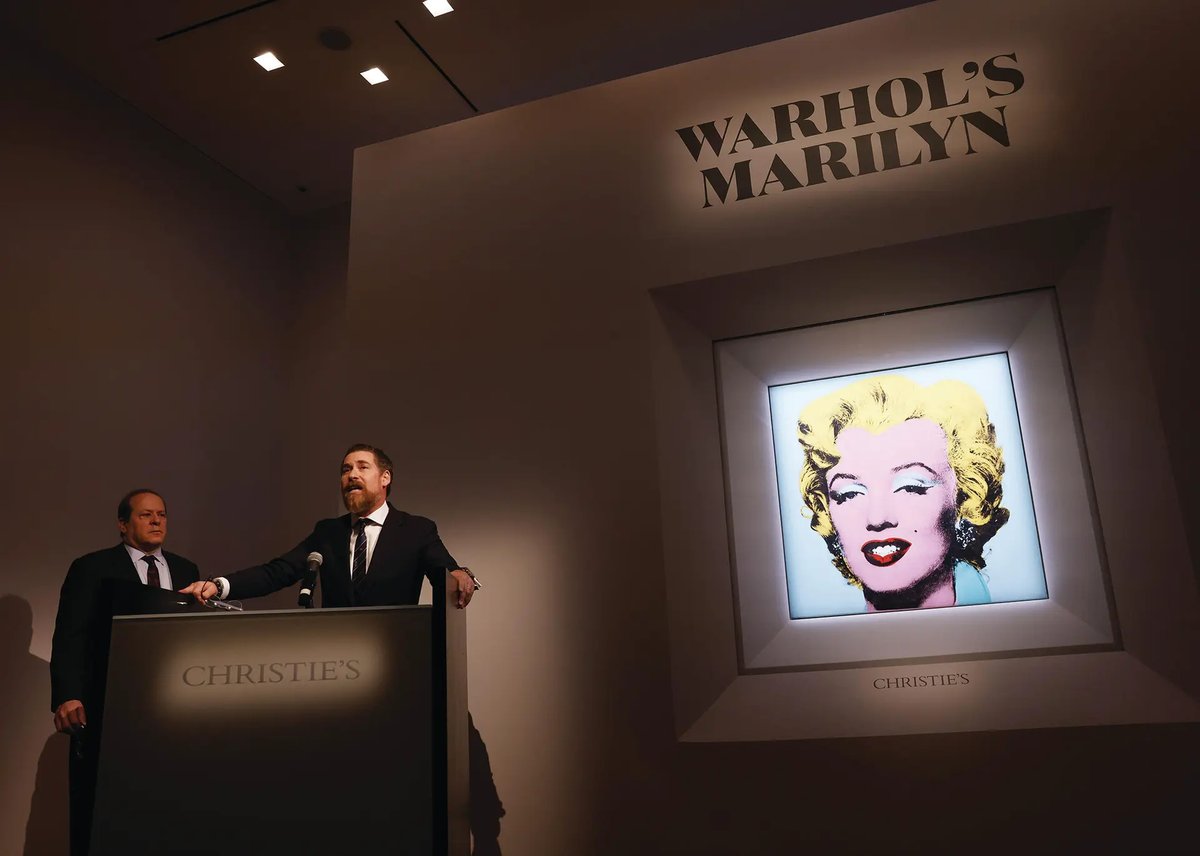

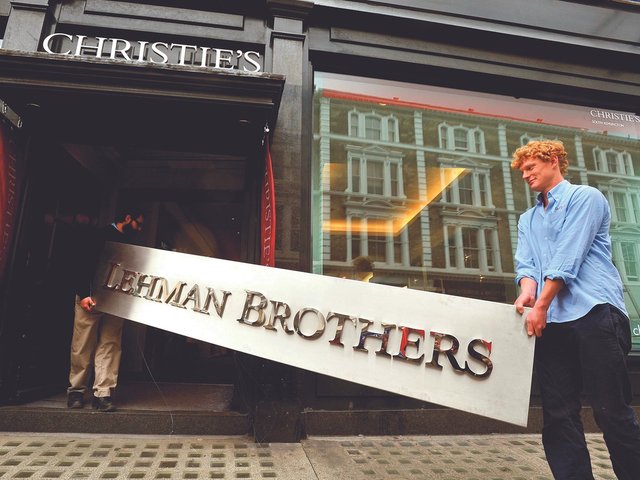

A final tranche of 20th- and 21st-century works from the “peerless collection” formed by New York divorcees Harry and Linda Macklowe topped up the total to $922m, making this single-owner offering the “most valuable ever sold at auction,” according to Sotheby’s. Phillips’s mixed-owner evening sale of modern and contemporary art racked up $225m, a record for the company. The previous week, Christie’s had sold Andy Warhol’s 1964 Shot Sage Blue Marilyn to Larry Gagosian for $195m, the highest auction price ever achieved for a 20th-century work.

“The art market no longer encompasses the market, it just encompasses auctions. It’s really the only thing that people are talking about,” says Lisa Schiff, the founder of the US-based SFA Art Advisory, commenting on the edge that livestream technology and global marketing have given the international salerooms since the advent of Covid.

Sotheby’s says that its various livestream sales drew 3.6 million views during its May marquee week. But the auction houses’ ability to shape wider perceptions of the art market has led to some hyperbolic messaging.

Special Guest (2019), by the Los Angeles-based artist Lucy Bull, sold for ten times its estimated price, going for $907,200 © Lucy Bull

According to Sotheby’s data, this latest series of New York sales at the three main houses was the “biggest auction season the market has ever seen”. But numbers crunched by the London-based art market analysts Pi-eX disagree. Their independently gathered figures show that May was in fact the third highest-grossing series of auctions on record: the grand total of $2.84bn was short of the $2.93bn achieved in May 2018 and the $2.89bn taken back in May 2015.

Warhol’s silkscreened Marilyn, one of a series of five such large-scale versions, was described by Alex Rotter, Christie’s chairman of 20th- and 21st-century art as “one of the greatest paintings of all time”, standing alongside Botticelli’s Birth of Venus and da Vinci’s Mona Lisa.

Wow. But if that really were the case, why did this ne plus ultra of Pop Art sell to Gagosian below its punchy estimate of $200m? Is it that a Hollywood superstar who died 60 years ago is no longer the relatable icon she once was? Or did the world’s population of more than 2,000 billionaires simply think that there are better ways of spending that kind of money than on art?

The reality of bidding

The world is being told that the top end of the art market is booming once again, but some new realities are lurking beneath the shiny numbers.

To be sure, the combined $922m achieved by Sotheby’s last month and in November for the 65 works from the Macklowe collection was a testimony to the enduring appeal of the divorced couple’s classic Upper Manhattan taste for brand artists such as Warhol, Rothko, Twombly and Richter, exercised over more than 50 years. Proceeds well above the rumoured global guarantee of $650m seemed to underline the status of these canonical names as enduring “blue-chip” investments, at least when offered from a long-established named collection.

But there was noticeably less demand for big-ticket works by established white male names when offered singly by anonymous sellers.

One of Cy Twomby’s large and hitherto much-prized late 1960s “blackboard” abstracts was guaranteed to make at least $40m in Sotheby’s mixed-owner contemporary sale. Back in 2015, a similar Twombly “blackboard” sold at auction for $70m. This latest example sold to a single bid from the third-party guarantor for a below-estimate $38m, a price reflecting the discounts that can be enjoyed by auction backers.

Just four lots earlier, Francis Bacon’s Study of Red Pope (1971), which had failed at auction five years before, was also guaranteed to sell for $40m. One extra bid knocked out the guarantor, resulting in a fee-inclusive price of $46.3m. A single bid that would normally be an increment of, say, $100,000, here cost $8.3m.

“If you’re a collector, why register to bid with a paddle if you can guarantee a work and get a discount?” says William O’Reilly, president of the New York branch of the advisers and dealers Dickinson.

But if more wealthy collectors wise up to the advantages that guarantors enjoy as buyers, this in turn may put off paddle-registered bidders from paying extra, which in turn could suppress demand for classic blue-chip works. Saleroom guarantees are already difficult enough to understand, but the recent ruling by a New York federal court that auction houses no longer have to declare such arrangements has the potential to make this situation even more obscure, further deterring inexperienced buyers.

According to Forbes, the world population of billionaires—individuals who can comfortably spend $200m on an artwork—increased from 1,209 in 2011 to 2,755 in 2021, their aggregate wealth ballooning almost three-fold from $4.5 trillion to $13.1 trillion. During that same period, global auction sales of fine and decorative art declined from $32.4bn to $26.3bn, says the data of the annual Art Basel and UBS Art Market Report.

“The art market has been flat for the past ten to 15 years,” says Roman Kräussl, a professor of finance at the University of Luxembourg and co-author of the 2016 study, ‘Does it Pay to Invest in Art? A Selection-Corrected Returns Perspective’.

Buy now, worry about value later

“Maybe the ultra-rich realise with all this data around that the returns are not in two digits,” says Kräussl. “When I calculate the return on art, it’s about 5%, with costs on top.” By comparison, S&P 500 stocks have yielded average annual returns of about 14.7% over the past ten years, according to Business Insider.

“People who buy blue-chip art like a classic $25m Richter aren’t buying it foremost as an investment, but mostly as a hedge against downside risk,” Kräussl says.

But what about the people clamouring to bid six and seven digits for paintings by young, Instagram-favourited “red-chip” artists like Anna Weyant, Flora Yukhnovich and Lucy Bull that recently sold in galleries for five digits? Are they buying for investment?

For Kräussl, and for many other market observers, this is simply a sign of a younger cohort of clients with too much liquidity (what the rest of us call “money”) chasing too few available works by too few fashionable names. And buyers are rich enough not to care too much about investment.

“You’ve sold a startup for $50m. You’ve got white walls. What do you put there? Not a Richter. That’s old school. But people are afraid of buying the wrong art,” Kräussl says. “It has to be politically correct. It has to be gender OK. It has to be race OK. And then you can say at the dinner table, ‘I bought this at Phillips.’ It’s a stamp.”

The record $225m total achieved in New York by Phillips, which has been specialising in emerging art for years, as well as the frenzy of bidding the following night at Sotheby’s $72.9m The Now sale of 23 works, by “the most exciting artists today”, typified this shift from blue to red, chip-wise. The $907,200 given for a 2019 abstract by Los Angeles-based Lucy Bull, represented by David Kordansky, was one of nine new auction records at Sotheby’s. The Bull artwork sold for more than ten times its pre-sale estimate.

“What’s going up? Everyone wants to get in on it. There’s nothing here that makes sense in a traditional value-making scenario,” Schiff says. She remains convinced that though there’s plenty of money to be made by flipping, art is an investment that performs better in the long-term. “You can make money buying and selling,” she adds. “[But] you can make a fortune holding.”

The Macklowes certainly did, though it took them half a century to get there. Can today’s digitised art buyers and sellers wait that long?