When Kevin Hearn, a keyboard player and guitarist in the Canadian band Barenaked Ladies, bought a painting ostensibly by the pioneering Indigenous artist Norval Morrisseau, he never imagined he was about to become enmeshed in a sinister web of art forgery, drug dealing, and sexual assault stretching from Toronto to the snowy wilds of northern Ontario.

“I just wanted to buy a painting, really,” Hearn says in a new documentary directed by Jamie Kastner, There Are No Fakes, released via iTunes in the US last month (and due to appear later in the UK on SkyArts). “I found myself in this complex, dark story that went beyond art fraud.”

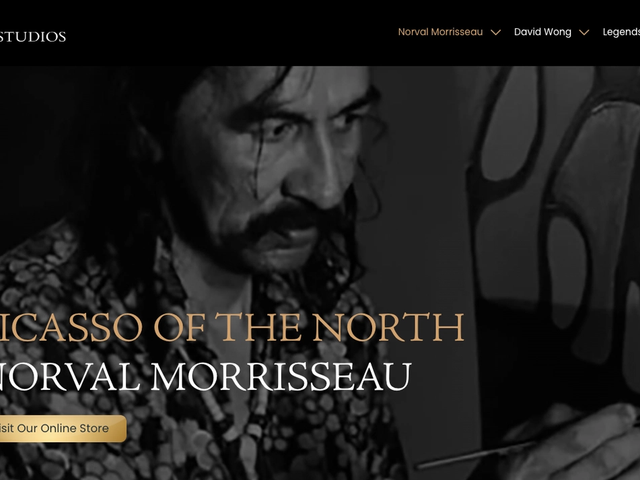

Hearn paid C$20,000 ($15,000) for a canvas called Spirit Energy of Mother Earth. But when he lent it to an exhibition a few years later, a curator sounded an alarm; it was not an authentic work by Morrisseau, a charismatic figure often described as the “Picasso of the North” who died in 2007.

There Are No Fakes recounts Hearn’s battle to get compensation for the fraudulent work, bought from the Toronto-based Maslak McLeod Gallery. The film’s host of colourful characters includes ivory-tower art historians, drug-addled forgers, thuggish art dealers and a predatory villain at the centre of the web: Gary Lamont, appearing in one photo wearing a row of giant gold rings like knuckle-dusters.

Hearn’s civil suit finally succeeded. After appealing an initial court decision against him, he was awarded C$60,000 ($41,700) in damages last year. Following a criminal investigation, Lamont was sentenced to five years in prison in 2016 for sexual assault; police are still investigating the forgery ring. One art dealer in the film, Don Robinson, estimates that Lamont’s ring may have produced as many as 3,000 fake paintings.

“[It’s] the greatest art scam in Canadian history,” says Robinson, who suffered a stroke because of the stress he endured in his campaign against a market awash with forgeries.

“The more you dive into a pool of garbage, the more you get to know the garbage within it,” says Ritchie Sinclair, Morrisseau’s former assistant and another key figure in exposing the scandal.

Kastner’s deep dive into this sordid, wintry world blasts sizeable holes in stereotypes about clean-living, law-abiding Canadians. It includes interviews with several eyewitnesses to the forgery operation, including one artist, Tim Tait, who says he painted works for Lamont, to which Morrisseau’s forged signature was later added.

“I did it to get my fix,” Tait says with endearing honesty. “Crack, coke, Oxycontin.”

Dallas Thompson, an accomplice of Lamont’s, recalls around 26 trips to Calgary to sell forged paintings over a three-month period in 2006 and 2007. But Thompson was also among the victims—he says Lamont raped him hundreds of times.

It is voices like Thompson’s that take this documentary beyond the true-crime genre: it is also an uplifting tale of broken people who muster the courage to take the enormous step of telling the truth. Thompson was the first to speak up in 2012: after that, other victims came forward.