What is the afterlife of an art forgery? Numerous stories on counterfeits end once the trickery has been unmasked, the coterie corralled and the investigation closed. But in some cases, known fakes eventually move on to become something surprising: practical tools used by art and educational institutions to sharpen scholars’ connoisseurship.

Consider the Courtauld Gallery’s Art and Artifice: Fakes from the Collection, a 2023 exhibition that showcased the institution’s collection of art forgeries, including those expressly gifted to the gallery as teaching aids. Although the show spanned counterfeiting in paintings, sculpture and even ceramics, 63% of the works on view were drawings. This skew makes sense, as drawings are particularly susceptible to the tricks of the forgery trade: they are rarely signed, those that are signed were often produced by the artists’ assistants or workshops, the artists themselves often made copies of their own drawings and many collectors at the time made copies as part of their connoisseurial activities.

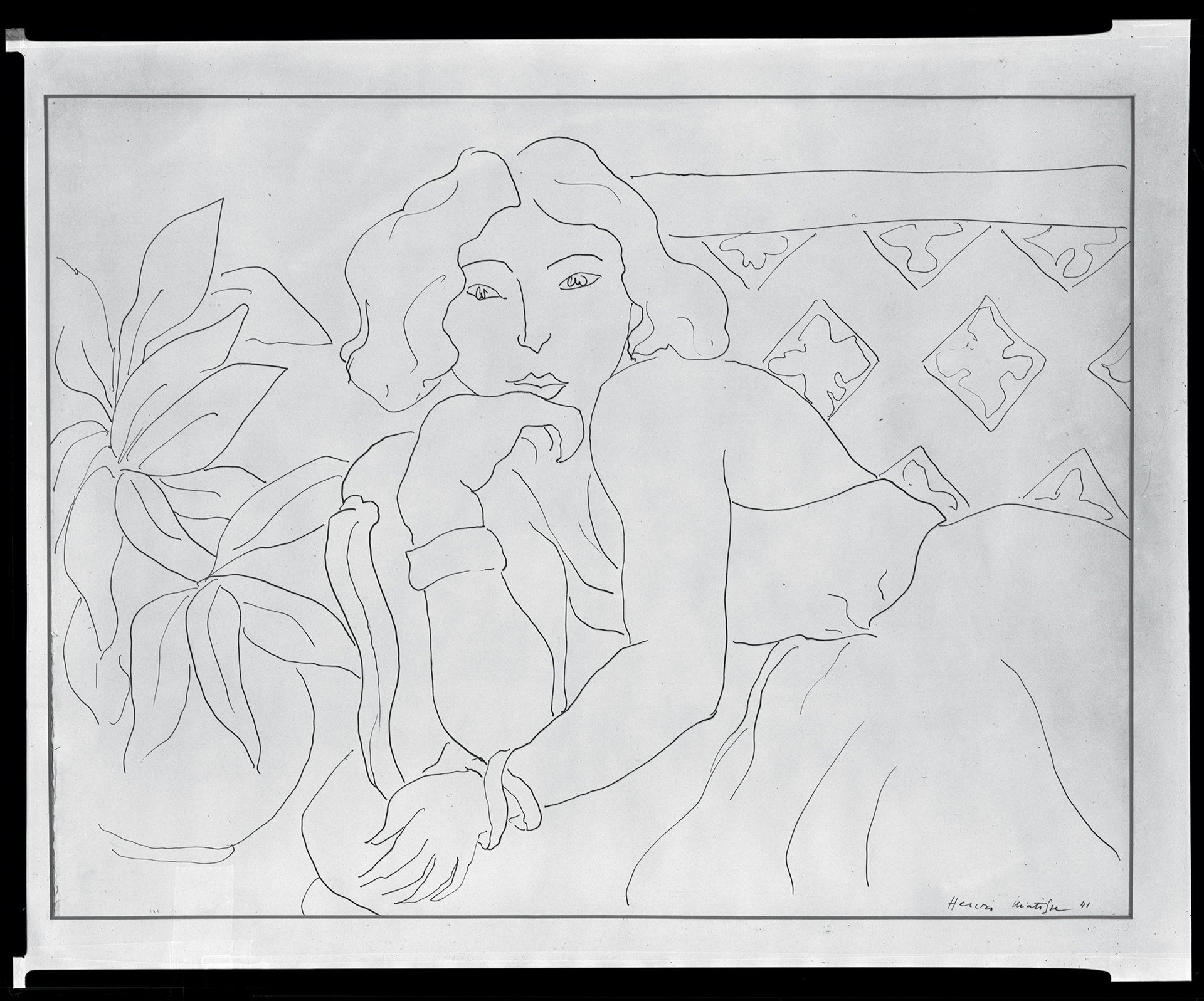

Teaching with forgeries is far from a recent phenomenon. Margaret Morgan Grasselli, the visiting senior scholar for drawings at the Harvard Art Museums (who until 2020 was the curator of Old Master drawing at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC), recalls being faced with a Matisse drawing faked by the prominent forger Elmyr de Hory in her sophomore tutorial at Harvard in the early 1970s. “One of the tricks was the shape of the pupil,” says Grasselli, who remembers the eyes of De Hory’s fake as distinctively “star-like”. Grasselli continued the legacy of close-looking by teaching a freshman seminar on drawings in January 2022, and while she primarily used workshop copies rather than forgeries, she acknowledges the potential of fakes as great future teaching tools.

Elmyr de Hory, Woman Reclining on a Sofa (1941) in the style of Henri Matisse, from the collection of the Harvard Art Museums Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Anonymous Gift. Photo © President and Fellows of Harvard College

Grasselli’s experience alludes to Harvard’s extensive collection of fake drawings. Under the leadership of Agnes Mongan, the curator of drawings at the Fogg (present day Harvard Art Museums) and, later, its director, the museum welcomed exposed forgeries into the collection primarily to remove the works from circulating in the art market. But once in the collection, they were considered scholarly aids. Among the known counterfeit works at the Harvard Art Museums is a category curators often refer to as “Fragonoffs”: 20th-century forgeries made in the style of the Rococo artist Jean-Honoré Fragonard that were brought to the market by Alexandre Ananoff, a Russian French space expert turned art historian.

Ananoff was outed as a fraudster in 1978 by the journalist Geraldine Norman and her then-unseen collaborator Eunice Williams (who at the time was assistant curator of drawings at the Fogg and is now an independent Fragonard specialist). Yet, a number of these drawings remain within institutional collections or still circulate in regional art markets today as purportedly authentic Fragonards. Harvard Art Museums declined to comment on whether these forgeries are presently used for teaching. However, this author participated in a workshop in March 2017 on collecting for an art museum run by the Harvard Art Museums with the department of history of art and architecture that included studying these forgeries, indicating that they were still used as teaching tools in select circumstances as recently as seven years ago.

The process by which the Fragonoffs circulated exemplifies the complexity of identifying copies and fakes of Old Master drawings. Ananoff authored the four-volume catalogue raisonné on Fragonard’s drawings in the 1960s that included falsified historical provenances of around 100 fake drawings and wrote academic articles claiming to have discovered the way in which Fragonard made copies of his sheets—which in turn made the forgeries seem all the more legitimate. Perrin Stein, the curator of drawings at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the organiser of its 2016 exhibition Fragonard: Drawing Triumphant, notes in the exhibition catalogue that it was “the very fact of Fragonard’s own habitual creation of multiple versions that gave cover to copyists of ill intent”, alluding to how the artist’s own process of creation ultimately facilitated the infiltration of fakes.

In some cases, the educational value of fakes can influence even the most esteemed public collections. For instance, the Met has the rare privilege of being able to compare at least one fake to the original. One of two Fragonoffs in the collection, The Sultan (After Fragonard)was deemed a forgery in 1988. In 2005, the original version of The Sultan was brought to the Met for study by a private collector and subsequently gifted to the museum—partly to help teach drawing connoisseurship through comparative study, according to a Met Bulletin article from 2009.

According to Stein, the close study of forgeries benefits all categories of viewers. “For collectors, dealers, curators and conservators, it sharpens skills of observation,” Stein tells The Art Newspaper, adding: “For students and members of the public, connoisseurship often seems like the province of experts. An understanding of what to look for breaks down insider/outsider walls and fosters engagement.”

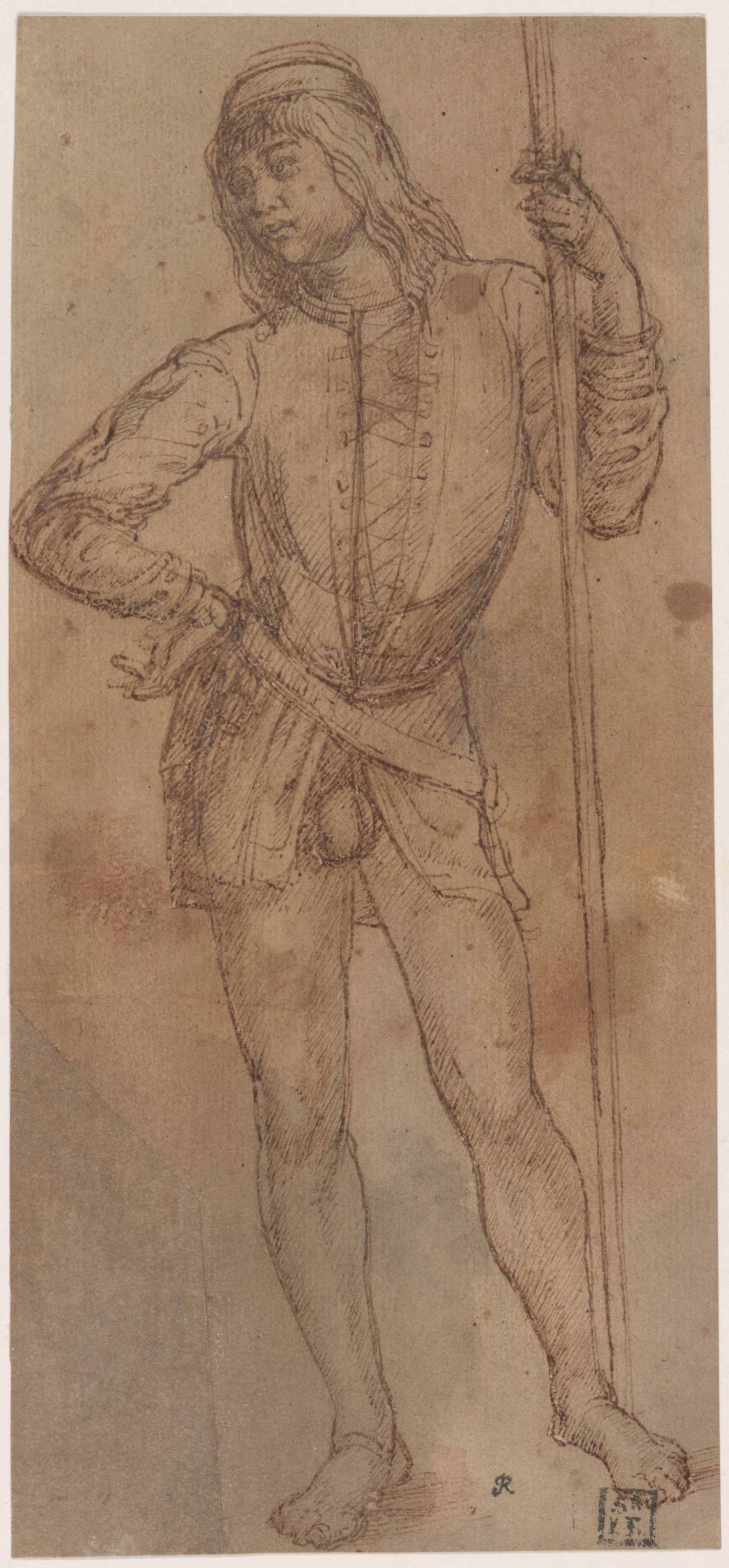

The educational demand for first-hand learning from fakes remains robust. In December 2022, the Morgan Library and Museum in New York held a seminar on forgeries of Old Master drawings, organised by John Marciari, the head of the museum’s department of drawings and prints, and David M. Stone, a professor emeritus at the University of Delaware. Held for a small audience of graduate students, the seminar stressed close-looking of modern and historic forgeries of drawings by artists such as Albrecht Dürer, Rembrandt, Guercino and Eugène Delacroix, as well as the historical circumstances that engendered them. The seminar included an infamous drawing purportedly by Francesco del Cossa that was instrumental in revealing the forgeries of its actual maker, Eric Hebborn, in the late 1970s.

Eric Hebborn, Standing Youth Holding a Staff, 20th-century forgery in the manner of Francesco del Cossa, from the collection of the Morgan Library and Museum Courtesy Morgan Library and Museum, New York

“The forgeries seminar was one of the most popular seminars the Drawing Institute has ever organised,” Marciari tells The Art Newspaper. “I've subsequently been asked to repeat it for the classes of several professors teaching courses on drawings, as a Silberberg lecture at [New York University’s] Institute of Fine Arts and as a masterclass for our circle of collectors. I also now include at least a forgery whenever I lead a session on connoisseurship.” Asked about drawing scholars’ interest in learning through fakes, he says: “There seems to be a perpetual fascination with forgeries—a kind of schadenfreude, perhaps, knowing that even an august institution like the Morgan has been duped in the past—but that also often means that students' curiosity is stimulated and that they look more intently.”

The perennial fascination with the topic endures. Marciari will lead a workshop on forged Old Master drawings on 28 October as part of a conference organised by the Drawing Foundation in New York. The Morgan is not new to embracing the potential utility of forgeries. Its 1978 exhibition The Spanish Forger focused on a modern counterfeiter who produced panel paintings and manuscripts passed off as Medieval—and who, coincidentally, was unmasked in 1930 by the Morgan’s first director, Belle da Costa Greene, herself the subject of a new exhibition there.

The educational interest in forgeries extends beyond institutional contexts. The monthly newsletter of the drawing platform Trois Crayons has featured a popular “Real or Fake?” section since its inaugural issue. “There is an inherent fascination with fakes, forgers and fraudsters in the art world, and that fascination has an appeal that extends well beyond the art ‘bubble’,” says Tom Nevile, a co-founder of the platform and the editor of its monthly newsletter.

Nevile notes that art history has harboured centuries of imitators with dubious goals. “Karel la Fargue (1738-93) began his career by innocently making copies after 17th century Dutch masters. However, he soon began to add forged signatures to these copies, leaving no doubt as to his true intentions,” he says, adding: “The artist-dealer Ignazio Hugford (1703-78) is thought to have copied original drawings from his own stock, which he would then sell as originals, intermingling his honest dealings with his less scrupulous ones (‘one drawing for the price of two’).”

Ultimately, whether drawing forgeries began as copies whose purpose was misunderstood over time or as deliberate attempts to deceive, the continued demand for their scholarly consideration underscores their considerable educational value. It also shows that their stories do not end with the revelation of their true makers.