New research by an art history PhD student reveals that the earliest known oil paintings by Edward Hopper—the celebrated artist of American solitude—were copies. At least four of Hopper’s 1890s landscapes, considered evidence of his precocious teenage talent, were copied from existing images. The original source for three of the works was in fact a popular magazine for amateur artists that reproduced paintings in colour with copying instructions.

Louis Shadwick made the surprising discovery while researching his PhD on Hopper’s early career at the Courtauld Institute of Art in London. In an essay published in the Burlington Magazine, Shadwick argues that “Hopper did not produce a single original oil painting until he enrolled at the New York School of Art in the autumn of 1900”, at the age of 18.

Born in 1882 in Nyack, New York, Hopper grew up in a middle-class Baptist family that encouraged his art and provided materials for him to study. He made numerous drawings of local life, including boats on the Hudson river, sketches of fishermen and churches. Until now, his early paintings were also thought to be rare depictions of Nyack, long forgotten in the attic of the family house. They only came to light after the artist’s death in 1967, having been acquired by a local Baptist preacher and family friend, Arthayer R. Sanborn.

In an interview with The Art Newspaper, Shadwick says he was researching the connections between Hopper’s formative works and his childhood home when he stumbled across a book with “very similar” winter landscapes by the American Tonalist painter Bruce Crane. He “started trawling auction websites on a hunch” and turned up a version of a Crane painting that matched an early Hopper known as Old ice pond at Nyack (around 1897). “That was the Eureka moment,” he says.

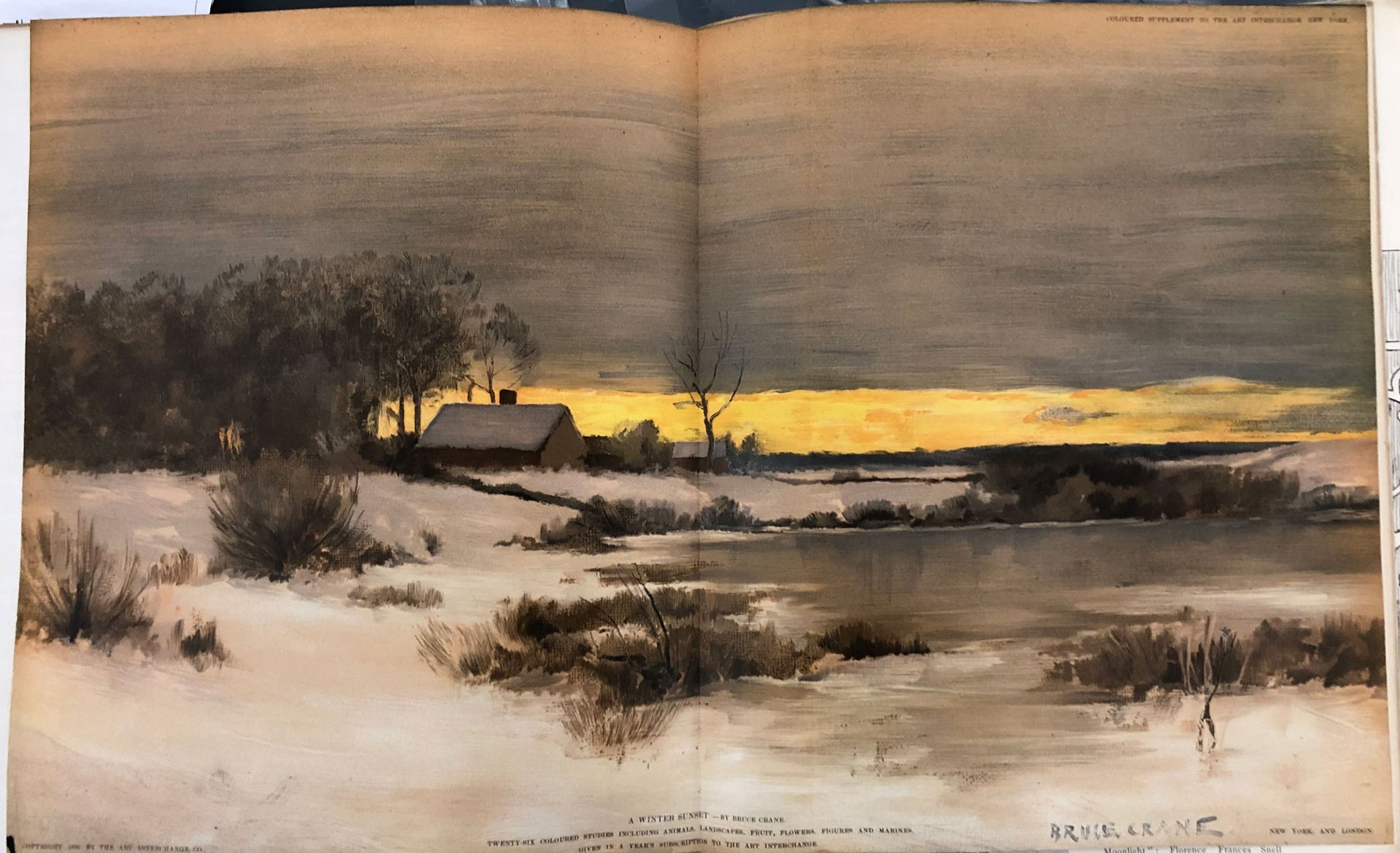

It took two more months of delving into illustrated journals from the period to understand how Hopper came to see Crane’s A winter sunset (1880s). The work appeared in the December 1890 issue of The Art Interchange, a magazine aimed at art students. That led Shadwick to an unattributed watercolour titled Lake View in the February 1891 issue that was a “dead ringer” for Hopper’s first signed oil, Rowboat in rocky cove (1895), painted when he was just 13. “The dots were joining,” he says.

Bruce Crane's A winter sunset (1880s) was reproduced in colour and with copying instructions in the December 1890 issue of The Art Interchange, a popular magazine aimed at art students Photo: Louis Shadwick

Googling “thousands” of turn-of-the-century art images, Shadwick was able to confirm that two further Hoppers were copies: Ships (around 1898) and Church and landscape (around 1897). The former is based on Edward Moran’s seascape A marine, reproduced by The Art Interchange in August 1886. The exact source of Church and landscape is not known, but Shadwick found the same snowy scene decorating a 19th-century porcelain plaque on an auction website. He is still hunting for the source of a fifth painting, Country road (around 1897), that he is “99% sure is going to be a copy as well”.

Though all the early copies except Church and landscape carry Hopper’s signature, Shadwick believes the artist had no intention of passing them off as originals. “I think he was signing them purely because they were his first oil paintings and he probably wanted to show them off to his family.” Hopper never discussed or exhibited these works, suggesting they held little personal significance.

They were misinterpreted posthumously, Shadwick explains, after the collection from the Hopper family attic passed to Sanborn. In the 1980s, he invented titles for the works and publicised them in connection with the artist’s youth in Nyack through exhibitions, articles and talks.

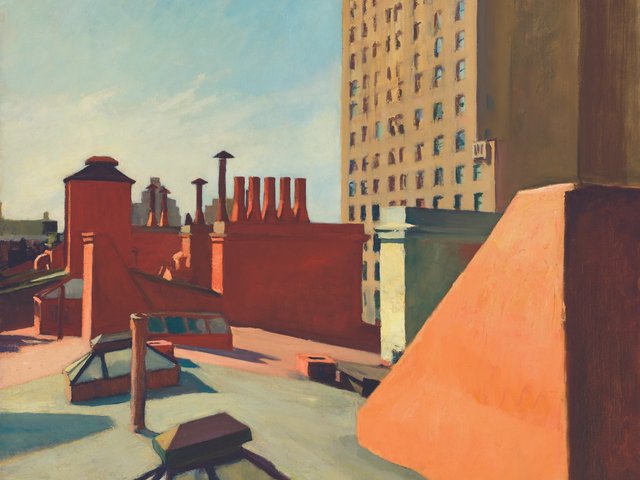

Hopper's earliest paintings were stored in the attic at his family home in Nyack, now the Edward Hopper House Museum & Study Center, until after his death in 1967 © Edward Hopper House Museum & Study Center

The teenage paintings also fit into a myth of originality perpetuated by Hopper and his supporters during his lifetime. “Decades of early Hopper scholarship cultivated the idea of a totally original talent, with no influences, that spoke to the American myth of the lonesome male,” Shadwick says. “What we need to do as art historians is take to task this idea of American individualism and bring it back down to earth. It’s not about trying to tarnish the artist, but being truthful that he was learning to paint via the same methods as so many other art students at that time.”

“That Hopper made painted copies as a teenager offers new detail to our understanding of his early years but is certainly not cause for a re-evaluation of this major figure,” comments Kim Conaty, the curator of a forthcoming Hopper exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, which holds the world’s biggest collection of the artist’s work. “Making copies of another artist’s work has been a standard part of artistic development and training for centuries,” she points out.

But there is potential for further discoveries among the vast Sanborn archive, from which 4,000 items were donated to the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York in 2017. Described at the time as the “holy grail of primary source material” for Hopper’s life and work, the archive “is still being processed and is not accessible to external scholars”, a Whitney spokesman says.

When the donation becomes available for wider study, “there could be so many clues to a much richer portrait of Hopper’s youth and development”, Shadwick says. “Going forward there’s going to be an exciting opportunity to find stuff that’s been missed for decades.”