Two museums in Edward Hopper’s home state of New York received rare archival donations this summer that promise to shed new light on his early life and long career. The Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City, which already holds more than 3,100 works by the artist—the world’s largest collection—has received a permanent gift of around 4,000 objects. A further 1,000 items of Hopper juvenilia are, fittingly, going on a ten-year loan to the Edward Hopper House, the artist’s birthplace in Nyack.

The materials come from the Arthayer R. Sanborn Hopper Collection Trust, a repository of Hopper’s work and memorabilia amassed by Sanborn, a family friend from Nyack, who died in 2007. His son, Philip, oversaw the transfer of the archives to the museums. The collection has not been without controversy. The author of Hopper’s catalogue raisonné, Gail Levin, has previously questioned Sanborn’s acquisitions, which he said included purchases from the estate of the artist’s wife. But when Josephine Hopper died in 1968, her will left all of Edward’s works to the Whitney (where Levin led research on the bequest). Both museums declined to comment further on the art historian’s claims.

The Hopper House’s executive director, Jennifer Patton, paid tribute to Philip Sanborn’s “effort to bring the two organisations together”. She says: “We are hopeful that we will develop ideas as we proceed with cataloguing that will formulate an important exhibition of Hopper’s formative years.”

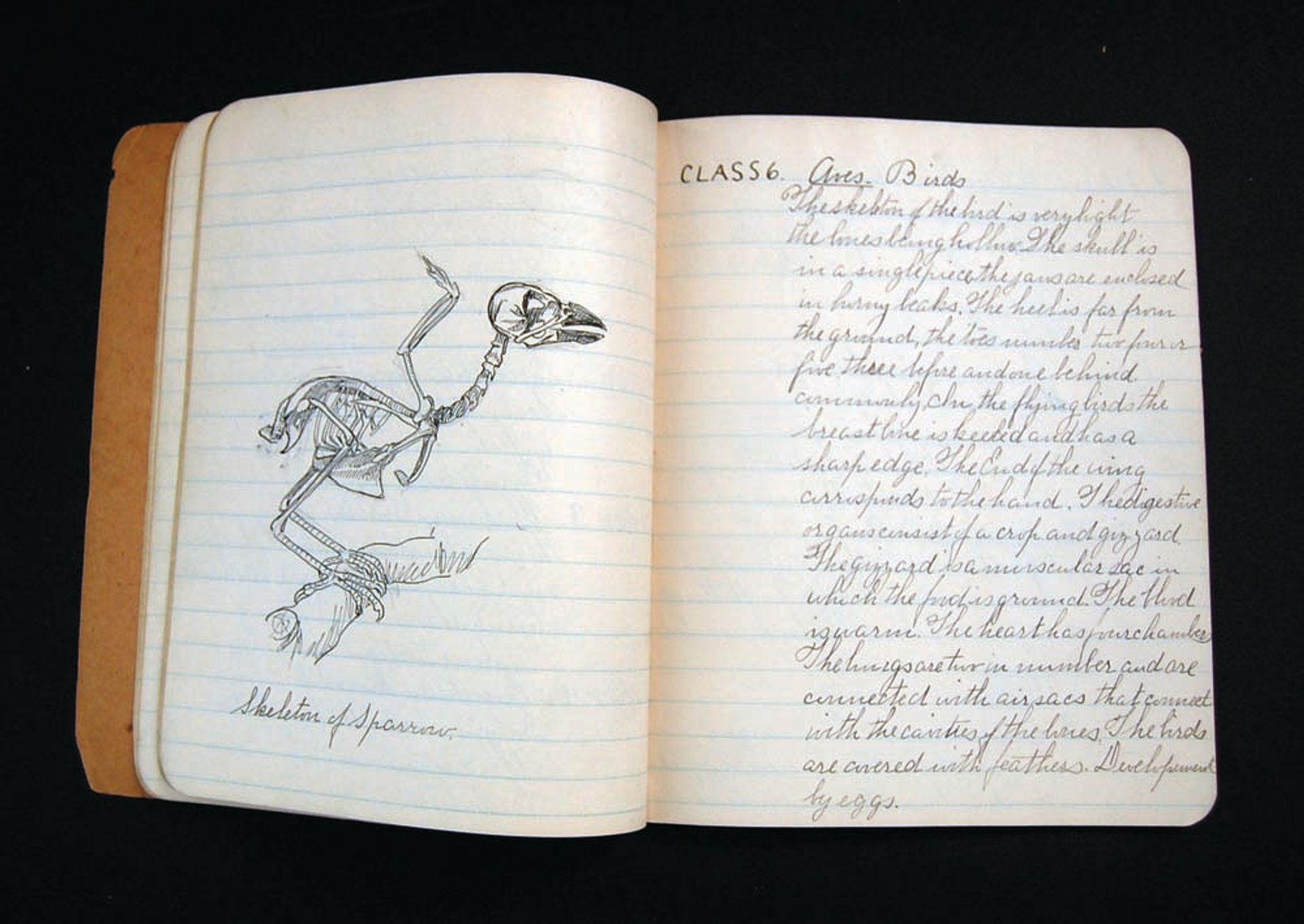

The house’s trove, renamed as the Sanborn-Hopper Family Archive, includes childhood mementos and drawings that reveal the artist’s precocious talent. While some of the items are already on display, it will take one or two years to mount a dedicated exhibition, Patton says. The house plans to create a new study centre for the archive as well as a research fellowship that will support future shows. The destiny of the works after the loan period is unconfirmed.

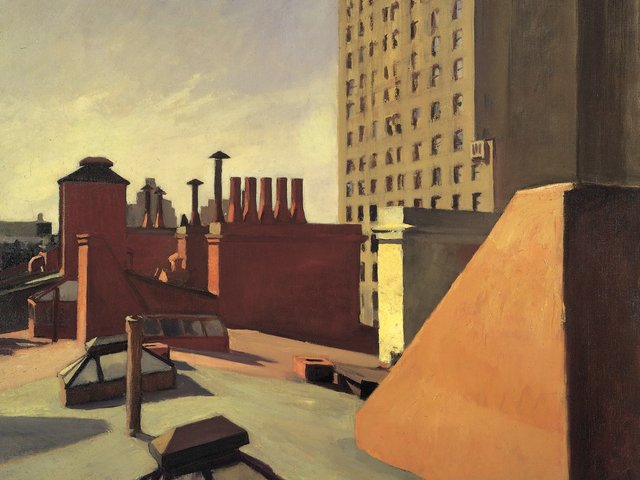

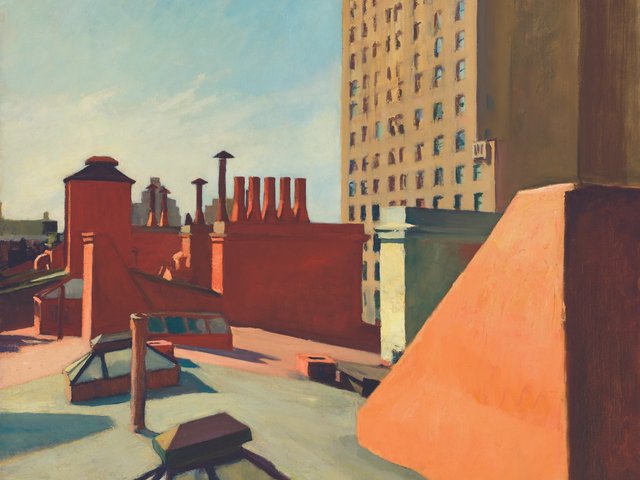

Cataloguing is also underway at the Whitney, which is exploring possibilities for exhibitions, publications and programming based on the Sanborn gift. With photographs, letters, dealer records and notebooks kept by the meticulous couple, the archive enriches the museum’s existing Edward and Josephine Hopper research collection, which is open to scholars by appointment. The donation is “the holy grail of primary source material for Edward Hopper and his milieu”, according to Carter Foster, the curator of the museum’s 2013 Hopper drawings exhibition.

Courtesy of the Edward Hopper House