It would plumb the depths of unkindness and ingratitude to ask any admirable person who has left this world to return to it in its presently wretched and perilous state. Yet that impulse has occurred to many—even to me—when wondering aloud what could, what would, Philip Guston have done with the very raw material for political caricature currently available?

We are inspired to speculate by Guston’s once obscure, now well-known cartoons of Richard Nixon and his gang of tragicomic White House thugs. That a chilling number of Nixon’s dirty tricksters are still hard at work in the shadows only whets our appetite for lethal lampoons of them. Of them, the most notorious are Paul Manafort and Roger Stone, with the dandified Stone now being the ripest target. Guston, unaware of their shadowy existence in the 1960s and 1970s, didn’t pen their absurd likenesses then, but Henry Kissinger, whom he drew repeatedly, is operating behind the scenes on a global scale.

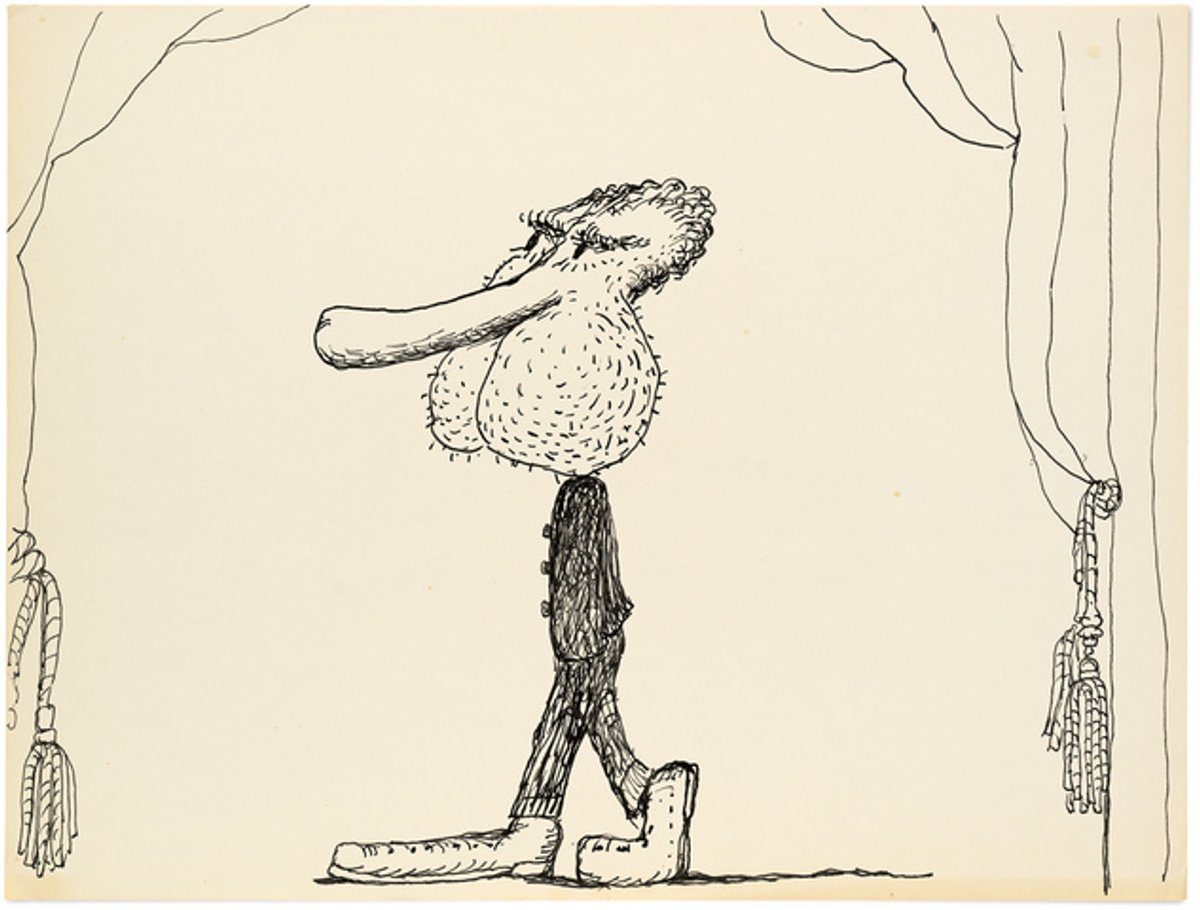

"Guston reconfigured the heavily bearded cheeks and ski-jump nose of the aptly named Dick Nixon into a hairy scrotum and dangling phallus"

The physiognomy of deviousness, greed, ruthless opportunism, risible self-importance and gobsmacking albeit garden variety stupidity provides artists of Guston’s bent and calibre with a virtually bottomless well of imagery—even as his subjects prove that there are no depths to which they will not sink. Honoré Daumier memorably transformed the wannabe Sun King Louis-Philippe into an all-but-shapeless pear, while Guston definitively reconfigured the heavily bearded cheeks and ski-jump nose of the aptly named Dick Nixon into a hairy scrotum and dangling phallus. In his metamorphic hands, what might become of the pomaded, self-parodying dumb blond prince of snide, the pompous Pompeo, the vapid poodle Jared Kushner and the unfunny dough-boy William Barr, defender of lawlessness and disorder in high places?

Of course, the contemporary cast of miscreants is larger still, but the impact of Guston’s cartoons of the Nixon presidency benefited enormously from his ability to select a few key players and toy with their features until they were—how shall I say it?—made ungreat again, in proportion to their roles and spotlight-grabbing gifts. The same would hold true in the unfolding surreality show that is the Trump administration. My guess is that aside from The Donald, The Attorney General and The Family—their cronyism is epic but Trump’s business model is really the Cosa Nostra—additional candidates for Guston-like lumpy, bumpy attention (read: derision) would include the perfidious enabler Lindsey Graham, the chinless, soulless legislative fixer Mitch McConnell and the surpassingly sinister villain of Nativist anti-immigration policy, Stephen Miller.

‘Us’, not ‘them’

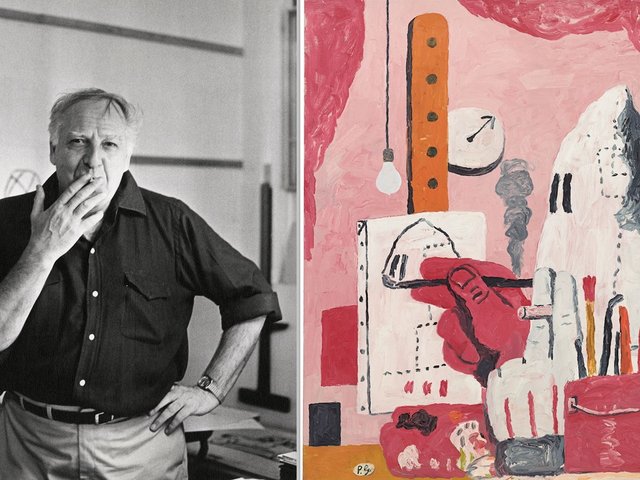

But there’s a hitch. When Guston first painted the Ku Klux Klan in the 1930s amid a surge of lynching, they exuded the otherness of pure evil. When he controversially returned to them in the 1960s, he understood that “they” were “us”. Accordingly, his hooded figures appeared as brickbat-wielding marauders but also as cigarette-puffing artists at their easels.

Guston’s identification with the Klan is counter-intuitive for many of his viewers, but more introspection would serve them well, since recent history has proven beyond a doubt that American racism, tribalism and know-nothingism are truly “our” problems—such that making fun of them is inherently bitter, double-edged self-mockery. The same holds true when it came to Guston’s ridicule of Nixon who, like him, hailed from a lower-class background and a small Southern California town.

Whoever tackles the arriviste Trump clan and coterie with the same artistry will need to be equally honest about their delusions, vices and ambivalences. Make way for him or her to find our mirror images.

More’s the pity, then, that given the opportunity to explore the perennially thorny issues of white supremacy and pervasive white complicity with its most extreme forms, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC and the other museums responsible for the Guston retrospective that was about to start its tour have postponed the show. I have been told that the prompt was push back from staff about an anti-lynching image from the 1930s, which was in effect the predicate for all of Guston’s later Ku Klux Klan imagery. If the National Gallery of Art, which has conspicuously failed to feature many artists-of-colour, cannot explain to those who protect the work on view that the artist who made it was on the side of racial equality, no wonder they caved to misunderstanding in Trump times.

• Robert Storr is a curator, critic, painter and writer

• Find our review of Philip Guston: a Life Spent Painting, here.