Since an announcement out of the blue last Thursday, the art world has reacted with widespread dismay to the decision of four museums to postpone the exhibition Philip Guston Now for four years. Though it was not referred to explicitly in the statement from 21 September—by Kaywin Feldman at the National Gallery of Art (NGA), Washington, DC; Frances Morris at Tate Modern, London; Matthew Teitelbaum at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; and Gary Tinterow, at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston—it seems that Guston’s paintings and drawings featuring hooded figures evoking the Ku Klux Klan were the issue.

One little-explored aspect amid the fury is the contradiction between the museums’ stated intention to “bring in additional perspectives and voices to shape how we present Guston’s work to our public” and the reality that, in the catalogue for the exhibition, they had arguably already done so. Among a diverse group of ten artists invited to contribute short essays on Guston to punctuate the exhibition catalogue, published earlier this year and commissioned long before, were the African American artists Trenton Doyle Hancock and Glenn Ligon. Both focus on the KKK imagery. In a statement sent to The Art Newspaper, Hancock echoed Guston’s daughter Musa Mayer’s words from last week, in saying that he was “‘saddened” that the exhibition has been postponed “because this is the moment those particular images should be seen”.

The museums’ statement explained the postponement as a response to the emergence of the “racial justice movement that started in the US and radiated to countries around the world”. The show would be postponed until 2024, they said, “a time at which we think that the powerful message of social and racial justice that is at the centre of Philip Guston's work can be more clearly interpreted”.

Few commentators have supported the museums’ position. But one prominent voice agreeing with the postponement is Darren Walker, the president of the philanthropic Ford Foundation and—perhaps more pertinently in this context—a trustee of the NGA. “What those who criticise this decision do not understand is that in the past few months the context in the US has fundamentally, profoundly changed on issues of incendiary and toxic racial imagery in art, regardless of the virtue or intention of the artist who created it,” Walker says in a statement. “An exhibition organised several years ago, no matter how intelligent, must be reconsidered in light of what has changed to contextualise in real time… By not taking a step back to address these issues, the four museums would have appeared tone deaf to what is happening in public discourse about art.”

Of course, the curators of the exhibition—Harry Cooper at the National Gallery of Art, Mark Godfrey at Tate Modern, Alison de Lima Greene at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston and Kate Nesin, at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston—could not have pre-empted the scale of the reckoning on racial justice that has developed since George Floyd’s death in May. But the Black Lives Matter movement was founded in 2013, and issues of racial justice and white supremacy have been uppermost in the mind of anyone following Western politics over recent years. The four curators seem to have been acutely conscious that to show Guston today necessitates reframing him within the context of present convulsions—the exhibition’s title is Philip Guston Now, after all. In their preface to the catalogue, the curators state: “today in the United States and across Europe we find ourselves embroiled once again in the kind of culture wars that defined the 1960s, facing levels of racism, violence, and polarisation that we have not seen for 50 years”.

Last week, Godfrey took to Instagram to attack the show’s postponement. Key to his argument was that museums should support artists, and not “abandon this responsibility to Guston” but also to the artists that he and the other curators had invited to write for the catalogue—notably, he named Glenn Ligon.

And you can see why. Ligon’s text is a powerful exploration of Guston’s Klansmen imagery, full of nuance, clear-eyed about the complexity and difficulty of addressing the subject. He describes Guston’s works as “detailing the mundane activities of white supremacy”. He explains the context in which Guston made the leap to figuration: “in the midst of a corrupt presidency, an escalating war in Vietnam, and unrelenting brutality directed at the civil-rights and black-power movements, Guston, unable to continue going to the studio ‘to adjust a red to a blue’, made a precipitous move from abstraction to figuration in order to explore issues of domestic terrorism, white hegemony, and white complicity.” Ligon ends with these words: “The comedian George Carlin once said, ‘The reason they call it the “American Dream” is because you have to be asleep to believe in it.’ Guston’s ‘hood’ paintings, with their ambiguous narratives and incendiary subject matter, are not asleep—they’re woke.”

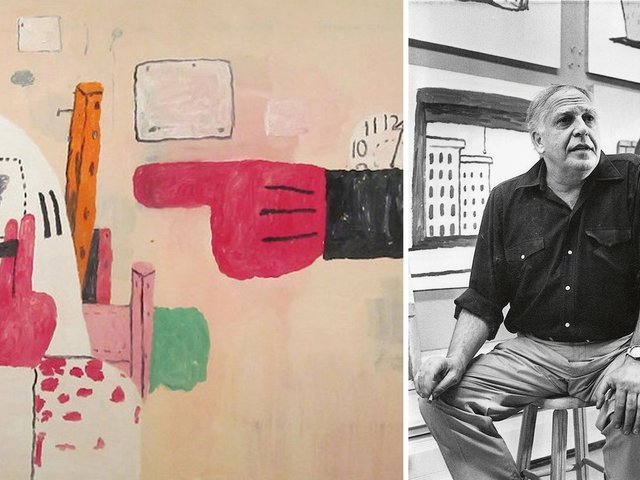

Trenton Doyle Hancock's SKUM: Just Beneath the Skin (2018, left) and Step and Screw: the Star of Code Switching (2020, right) © Trenton Doyle Hancock 2020. Image courtesy of the artist and James Cohan, New York. Photo: Phoebe d'Heurle

Hancock focuses in eloquent detail on Guston’s horrifying Drawing for Conspirators (1930), featuring the lynching of a Black man by Klansmen, with a lone, apparently more forlorn KKK figure in the foreground. “A quiet unease amplifies the drawing’s horrors; pointed in its indictment, it also shows subtler ironies and references,” Hancock writes. “Guston describes something beyond the occasion, something lurking under the white hoods.” Hancock, like Ligon, draws attention to Guston’s aim to attempt to get inside the heads of the Klansmen. As Guston put it: “What would it be like to be evil?” Hancock speculates: “Does [the foreground figure] represent the potential for humanity in those devoid of it?”

Hancock then describes how he has “found [his] way to new meaning by engaging Guston”, bringing the older painter’s Klansmen into canvases where they meet with Hancock’s character Torpedoboy, a Black superhero. “Generating this encounter was my way to confront an artistic father figure and examine our respective motivations… I wanted to show that hate organisations like the Klan still exist, congregating and operating in plain sight.” Some of Hancock’s latest paintings featuring the Klansmen and Torpedoboy are currently on view at James Cohan gallery’s two New York spaces (until 17 October).

In addition to expressing his sadness about the postponement, Hancock tells The Art Newspaper: “[Guston] made the case that the Klan was as American as apple pie. He didn't run from this very American conversation in the 1960s and neither should we now.” He also addressed one of the most troubling aspects of the museums’ claim that they need four years to find alternative voices and achieve “clear interpretation” of Guston’s work. “Why haven't institutions developed a deep and rounded cultural framing of Guston's politics on American whiteness already?” Hancock asks. “This conversation is happening whether institutions participate or not.”