Blindfolded and bound, a woman struggles to free herself from a plinth. The mortuaries are full. Crouching across a scaffold, one Klansman hurls a Bible and a crucifix from above, while another scales a ladder and swings a cat o’ nine tails overhead. These images wrestle for space in Philip Guston’s social realist masterpiece The Struggle against Terrorism (1934-35), a fresco in Morelia, Mexico, that he painted with his best friends Reuben Kadish and Jules Langsner.

Too monumental to dismantle from the wall of what is now the Universidad de San Nicolás and ship to London, moving pictures of the mural are projected in full colour across a whole gallery wall. It is a tapestry of humanity at its most valiant and its most depraved, a meandering collage of leaden forms that remind us of the heavy costs paid by the innocent in times of war. Like many of Guston’s paintings, the mural is about “the violence in the world, ever since I’ve been alive”, which was something universal, something “everyone experiences”.

Guston went to high school in Los Angeles with Jackson Pollock

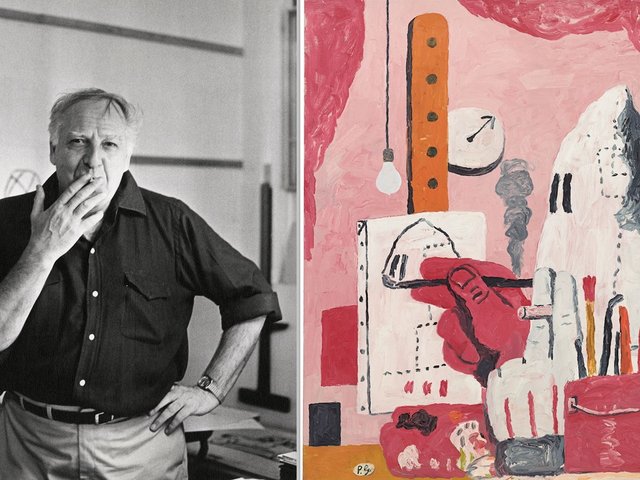

Philip Guston is this year’s revelatory winter exhibition at Tate Modern. The show is a mammoth undertaking that has brought together more than 100 works from an enthrallingly eclectic 50-year career. Beloved as the lush colourist of the Abstract Expressionist movement, Guston (1913-80) was first and foremost a painter’s painter who restlessly advocated for the social purpose of Modern art. The child of Jewish refugees who fled pogroms in Poland in 1905, Guston was born in Montreal and grew up in Los Angeles, where he went to high school with Jackson Pollock.

Successive tragedies marked the artist’s formative years. In June 1930, his father Leib hung himself in the back porch of the family home, ashamed that he had been reduced to working as a ragpicker. In 1932, a car rolled over and crushed his beloved brother Nat to death, and the same year, fascist sympathisers from the Los Angeles police stormed an exhibition in North Hollywood, armed with lead pipes and guns, and destroyed one of Guston’s murals protesting the infamous case of the Scottsboro Boys. They shot out the eyes and genitals of its figures.

These experiences pour like wet paint into Guston’s paintings: hangman’s ropes, knots and mob clubs populate so many works, while spectral figures tear silently at the social fabric. In Martial Memory (1941), lost boys or orphans assemble debris for weapons from the street while a foreign war rages out of view; holding broken sticks, cardboard and trash cans, Guston’s children take up anything they can to protect themselves.

Guston's Female Nude with Easel (1935) and Nude Philosopher in Space-Time (1935) Photo: © Tate (Larina Fernandes)

This tumultuous period of the self-taught Guston’s early career is thoughtfully attended to in a small, off-right room at the opening of the exhibition. Two early works—Female Nude with Easel (1935) and Nude Philosopher in Space-Time (1935)—are seen in the UK for the first time. In this extraordinarily dreamlike pairing, the two oils are mirrored as nude figures on the right stand—each with their face downcast—looking at objects representing art and anatomy. You immediately notice the influence of Giorgio de Chirico’s surreal amalgamation of things that should not exist together, as well as the compositional structure characteristic of Guston’s hero Piero della Francesca and the Tuscan’s serene symbolism of bodies alone in this world.

These are honest paintings by a lifelong anti-racist, the artistic equivalent of Hannah Arendt’s “banality of evil”

A vitrine displaying archival and found material demonstrates the artist’s early commitment to social justice and anti-fascism, especially organising against the Ku Klux Klan. These commitments take us to his powerful anti-war painting, Bombardment (1937), which stands as Guston’s testament to the aerial assault on Guernica by the Nazi Luftwaffe. If Pablo Picasso’s painting of the same subject moves the trauma of women and animals across the picture plane, then Guston’s version comes right at us: using a Renaissance tondo (circle) format, with an explosion at the centre, it is a universal image on the indiscriminate suffering of civilians during shelling, a picture of new warfare made using the techniques of the past.

Like the rest of his New York circle, by the late 1940s Guston gave up social realism for a sumptuous abstraction that delights in the joys of paint as light, of cadmium reds and yellow ochres. The Return (1956-58) and Native’s Return (1957) stand as some of Abstract Expressionism’s greatest hits, with titles that suggest homecoming. But Guston was always turning sideways and ignoring the logic of painting as something moving through history on a single track.

Guston's anti-war painting Bombardment (1937) Photo: © Tate (Larina Fernandes)

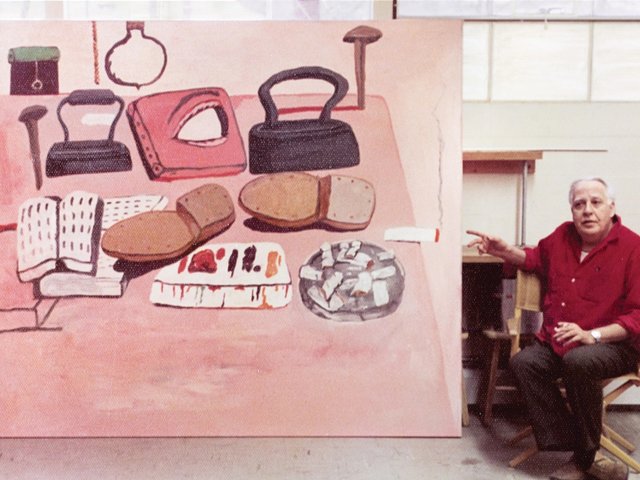

“There is something ridiculous and miserly in the myth we inherit from abstract art,” Guston said, seemingly against himself, “that painting is autonomous, pure, and for itself.” By the time of the Vietnam War, he looked at himself and asked: “What kind of man am I, sitting at home, reading magazines, going into a frustrated fury about everything … and then going into my studio to adjust a red to a blue?”

At Tate Modern, it is as though we are in the studio with Guston, experiencing this crisis of faith, as we transition through a darkened antechamber and return to an old subject: the Klan, but not like before. If the Klansmen of the 1930s were clearly an enemy to be fought, here they relax with cigarettes, paint self-portraits and go on road trips through the city. They are almost like us. By taking on this subject for an exhibition at New York’s Marlborough Gallery in 1970, Guston felt admonished by his devoted abstract peers, as though a prophet “excommunicated from a covenant”. His close friend, the composer Morton Feldman, never spoke to him again.

Now we arrive at the elephant in white robes, and the cancellation of the first iteration of this exhibition in September 2020 after the police murder of George Floyd. Back then, Tate Modern was kicked into line by the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, to abandon its partnered retrospective, until “the powerful message of social and racial justice that is at the centre of Philip Guston’s work can be more clearly interpreted”. Tate’s curator on the project, Mark Godfrey, resigned in protest. Outraged, a chorus of artists and critics argued that we needed Guston’s “powerful message” more than ever, and that the public should be able to make up its own mind. Implicit in the decision to postpone the exhibition is the impossible notion that there will ever come a time when Guston is no longer so acutely relevant, and the politics around which his work centres so fraught.

The museum directors lined up and said society was not ready; how wrong they were. Of course, we might ask: don’t these works humanise those who carry out hate crimes?

“I almost tried to imagine that I was living with the Klan,” Guston said. “What would it be like to be evil? To plan and plot.” But these are honest paintings by a lifelong anti-racist, works that are the artistic equivalent of philosopher Hannah Arendt’s arguments on “the banality of evil”, which does not say that vile actions are in any way ordinary, but that they are motivated by complacency and possibly perpetrated by our colleagues, friends or neighbours. In this work, Guston imagines his lumpen enemy with an honesty and a seriousness that balances their blockhead silliness. We leave wishing there were a thousand Gustons for our own time.

Three of Guston's paintings, from left to right: Dawn (1970), City (1969) and By the Window (1969) Photo: © Tate (Larina Fernandes). Glenstone Museum; Guston Foundation; Roman Family

What the other critics said

The exhibition has received a rave response, with a five-star review in The Guardian by Adrian Searle, who described Guston as “method-acting” the moves of the Klan and highlighted the artist’s relevance at a time when “stupidity, bigotry and a penchant for violence are always with us, and white supremacy is on the rise again”. Alastair Sooke, for The Telegraph, also gave full marks to a “timeless art that skewers evil”. Jackie Wullschläger, for the Financial Times, called the show “gripping in painterly expression and energy, awash with colour and drama, revelatory at every turn”.

• Philip Guston, Tate Modern, London, until 25 February 2024

• Curators: Michael Wellen with Michael Raymond