The first exhibition to explore Vincent’s olive groves now has new dates. Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum was originally to have presented the show this summer, but it has been delayed because of Covid-19. Van Gogh and the Olive Groves will instead start at the Dallas Museum of Art (17 October-6 February 2022) and then open at its Dutch venue next year (11 March-12 June 2022).

While recovering from his mental crises at the asylum on the outskirts of Saint-Rémy-de-Provence Van Gogh painted 15 olive scenes. They have been scientifically examined for the coming exhibition and nearly all will go on display. Reassembling the paintings (for the first time) has been a challenge, but hopefully the only missing ones will be two at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and another at Washington, DC’s National Gallery of Art, which cannot be lent because of donor restrictions.

Van Gogh started work in the olive groves in June 1889, a month after his arrival at the asylum, following the ear mutilation incident in Arles. A quintessential feature of the Provençal landscape, the trees must have seemed dazzlingly exotic to a northerner.

Mesmerised by their reflective, evergreen leaves, Van Gogh described their attraction to his mother: “There are very beautiful fields of olive trees here, which are grey and silvery in leaf like pollard willows.” Many of the trees around Saint-Rémy-de-Provence were centuries old, their rugged trunks a testament to their longevity (sadly, most of the ancient trees would later die during an extreme frost in 1956).

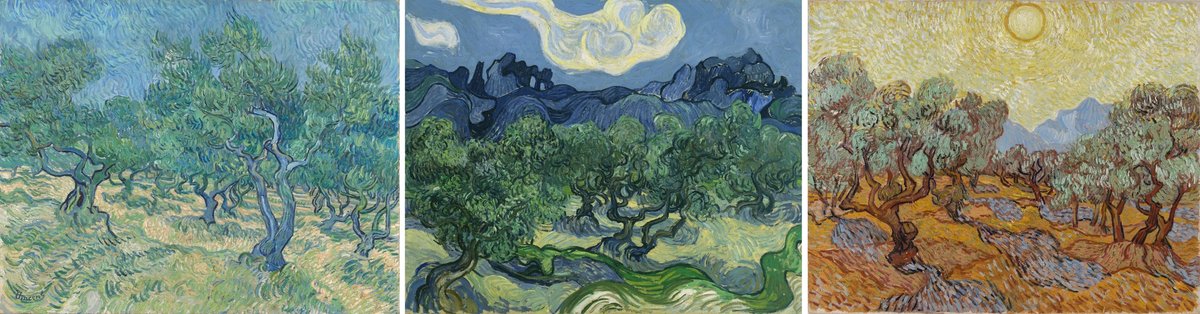

Van Gogh’s Olive Grove (June 1889) Courtesy of the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

One of his first efforts was a marvellous drawing, done swiftly with a brush and ink. His close observation of this grove would soon result in a series of paintings.

Van Gogh completed four paintings in June and early the following month, but in the middle of July he was suddenly struck down by another mental attack while working outside. The asylum doctor reported that Vincent had tried “to poison himself with his brush and paints”. His throat was extremely painful and he could not eat for days.

It took nearly six weeks to recover from the mental attack. Acknowledging that he had tried to commit suicide, Vincent explained metaphorically that “finding the water too cold”, he was struggling to regain the river bank. It was the prospect of being able to paint again that brought him back to life, and by late September he was once again allowed out of the asylum to work.

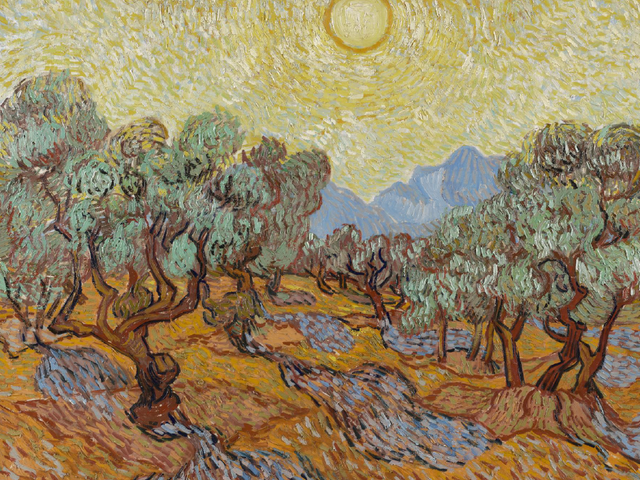

Van Gogh’s Olive Trees (September 1889) Private collection

Research for the Dallas-Amsterdam exhibition has now sorted out the sequence of the 15 paintings. Olive Trees, owned by an anonymous private collector, has been dated to late September. Vincent described its colours in a letter to his brother Theo: “Silver, sometimes more blue, sometimes greenish, bronzed, whitening on ground that is yellow, pink, purplish or orangeish to dull red ochre.”

A technical examination of the privately-owned picture reveals that its light-sensitive red pigment has faded, so originally it would have tallied more closely with the artist’s description. Vincent went on to tell Theo that it was “very difficult” to capture the silver effect of the leaves—but he would persevere and strive for success like “the way the sunflowers are for yellows”.

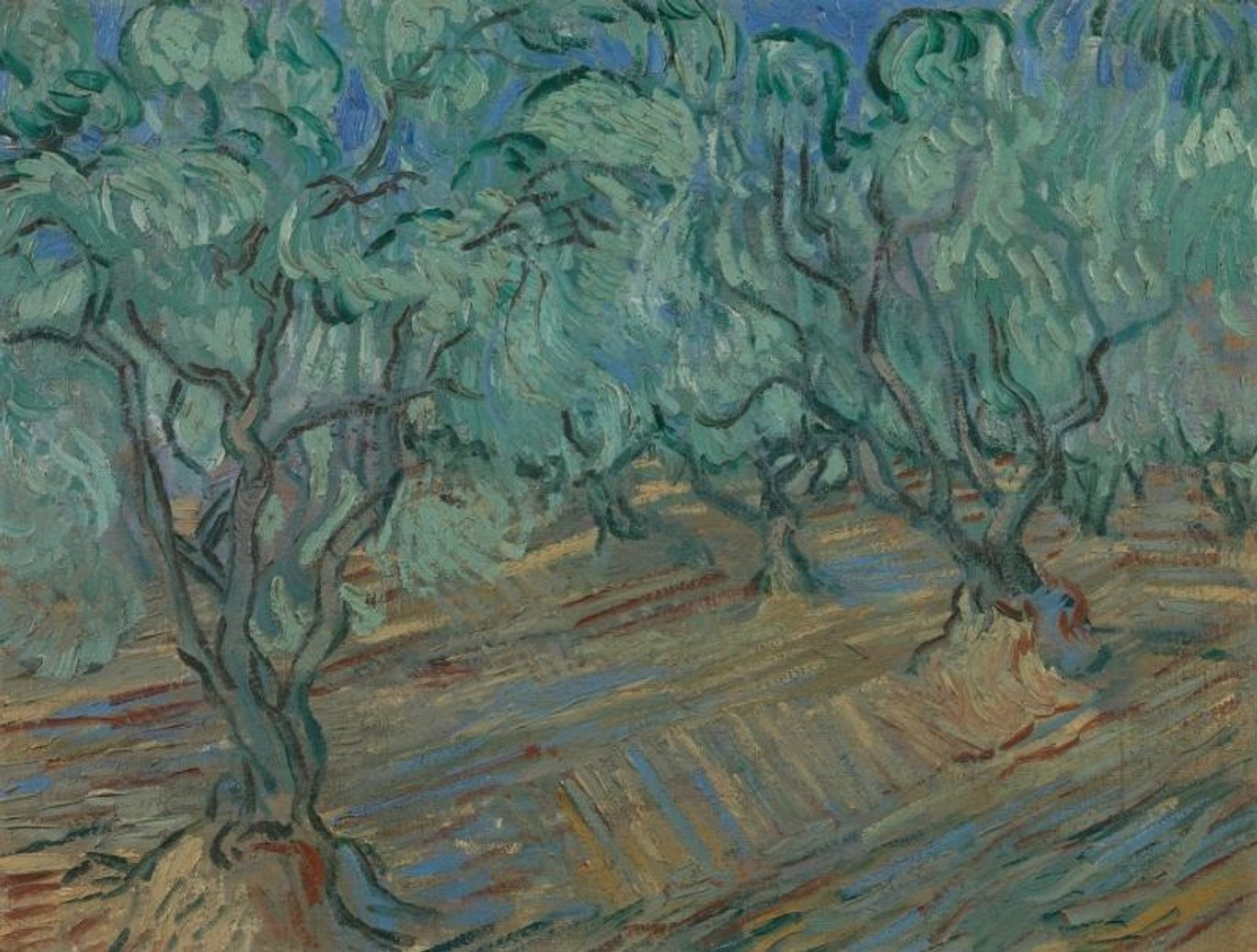

Van Gogh’s Olive Grove (September 1889) Courtesy of the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

Another painting, at the Van Gogh Museum, will also be redated to September 1889 (it is still on the museum’s website as a June work). Olive Grove, a relatively little-known work, displays great sensitivity in its colouring.

Among the noteworthy discoveries was finding that a grasshopper got stuck on the Olive Trees which is now at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, Missouri. The presence of the unfortunate insect shows that the painting was done outside, in front of the motif.

While eventually completing his series at the end of the year, Vincent had the idea that his paintings of Provençal olive and cypress trees should find buyers in England. He wrote emphatically to Theo, saying that they “ought to go to England, I know well enough what they’re looking for over there”. Vincent had worked as a trainee art dealer in London in 1873-75.

Unfortunately, Van Gogh was wrong about English taste, and it was not until decades later that any of his olive grove paintings found collectors in Britain: one was bought by the academic Michael Sadler in 1923 and two by the aristocrat Victor Schuster in the late 1930s. Sadler’s was later acquired by the National Gallery of Scotland for £1,600 in 1934 and Schuster’s works both ended up in New York at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

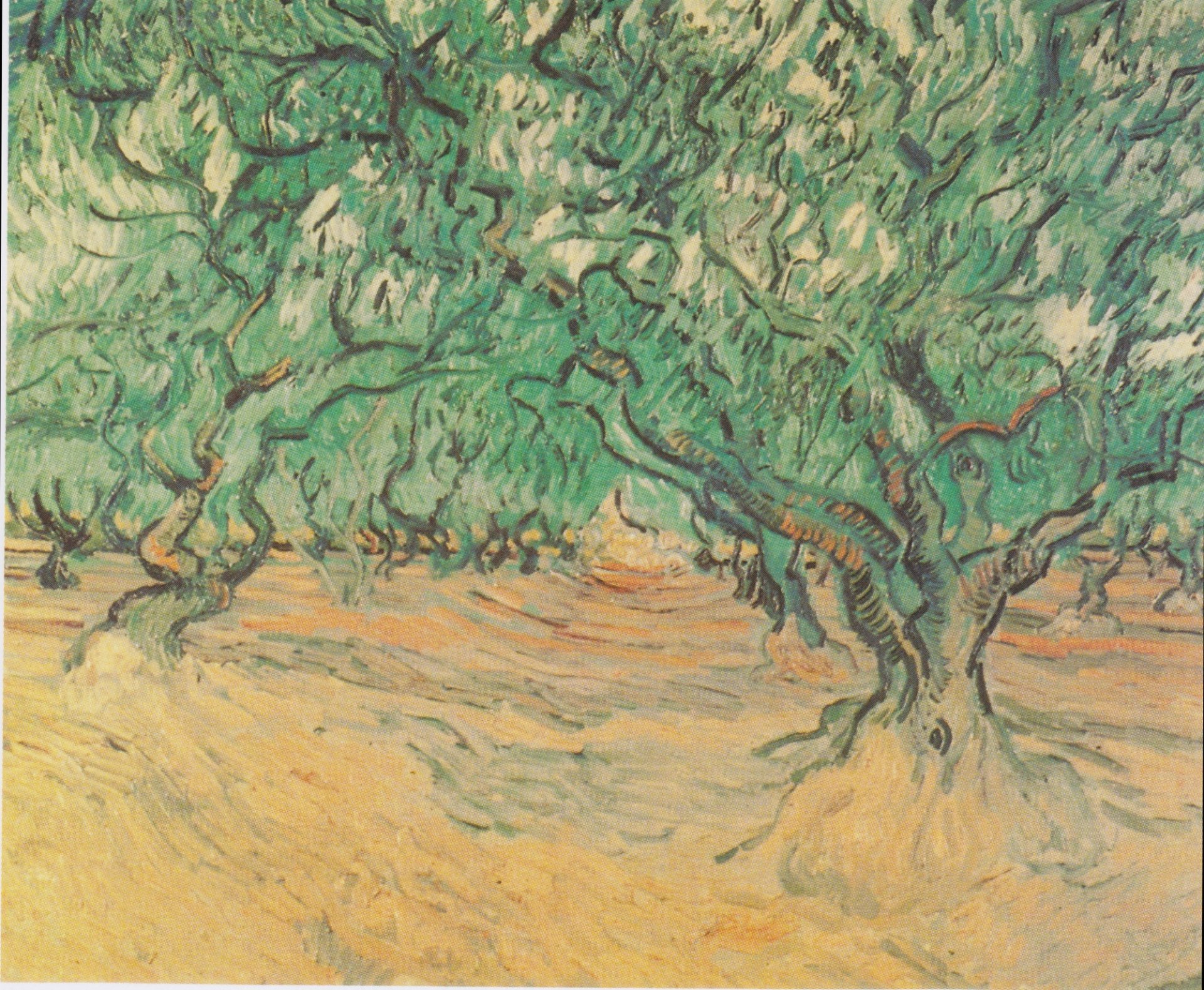

Van Gogh’s Olive Trees (June 1889) Courtesy of National Galleries Scotland

When Van Gogh departed from the asylum a year after his arrival he looked back on his efforts to capture the olive groves in the changing seasons: “When the more bronzed greenery takes on riper tones the sky is resplendent and is striped with green and orange; or even further on in the autumn, the leaves take on the violet tones vaguely of a ripe fig.” In May 1890 he left Saint-Rémy-de-Provence to head north on the final stop on his artistic journey, ending his life ten weeks later.