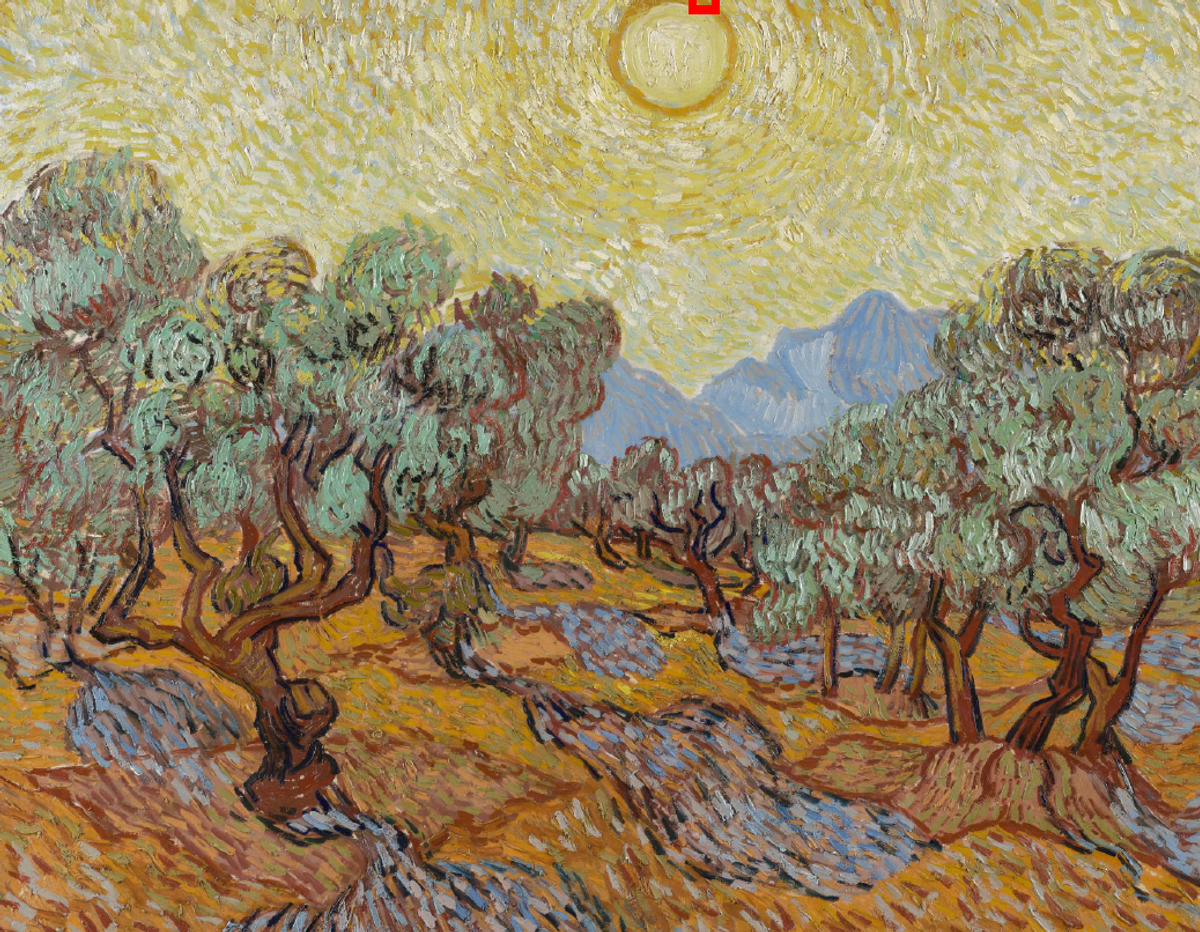

One of Vincent’s fingerprints has been found on the edge of Olive Trees (November 1889), belonging to the Minneapolis Institute of Art and now on loan to an exhibition at the Van Gogh Museum.

The Amsterdam show Van Gogh and the Olive Groves, which opened last weekend (until 12 June), reassembles most of his paintings of this motif from the year he was living at the asylum on the outskirts of Saint-Rémy-de-Provence.

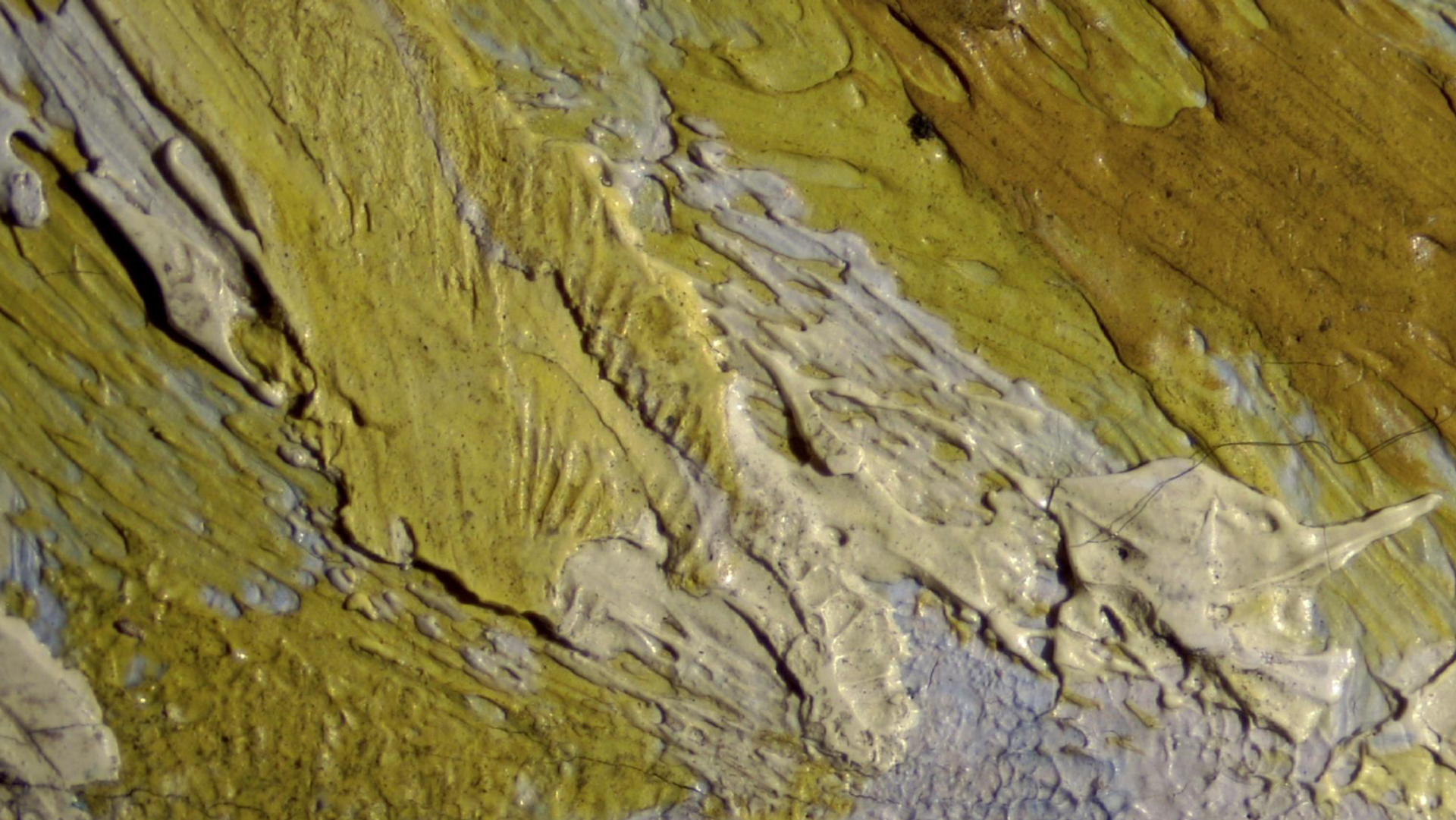

Photomicrograph of Olive Trees, showing the ridges of the newly discovered fingerprint in the centre. Photomicrograph taken using a stereomicroscope at the Midwest Art Conservation Center, Minneapolis, by Laura Hartman of the Dallas Museum of Art

To prepare for the exhibition, all 15 of Van Gogh’s olive groves series scattered around the world were systematically studied by curators and conservators. The show began at the Dallas Museum of Art, where it closed last month.

While examining Olive Trees, Dallas conservator Laura Hartman discovered traces of a fingerprint near the top edge of Olive Trees, just to the right of the prominent sun. The position of the imprint suggests that Van Gogh picked up the wet painting with his hand, balancing it by holding it near the middle of the canvas. Although this could have happened when he lifted the picture off the easel, it is more likely to have occurred while he was carrying it back to his studio room in the asylum, a walk of around ten minutes.

Vincent painted Olive Trees in late November 1889. As he wrote to his brother Theo, “I’ve been messing about in the groves morning and evening on these bright and cold days, but in very beautiful, clear sunshine”. He completed several landscapes, but this one appears to have been done in the early morning, just after sunrise - with a striking, but unrealistic depiction of “a big yellow sun”, as he put it to his sister Wil.

It is a late autumn scene, with patchwork of bluish shadows on the reddish earth. Using artistic licence, Van Gogh has not painted the shadows as they should fall, which would be directly towards the viewer, but instead has positioned them at an angle. Set beneath the powerful sun lies the silhouette of Les Alpilles (the Little Alps), a chain which runs just south of Saint-Rémy.

The smudged trace of a fingerprint on Olive Trees is not clear enough to positively identify it as that of the artist, but it is virtually certain that it is his. Van Gogh nearly always worked quickly, and often not so neatly, so he probably did not worry unduly about this minor damage.

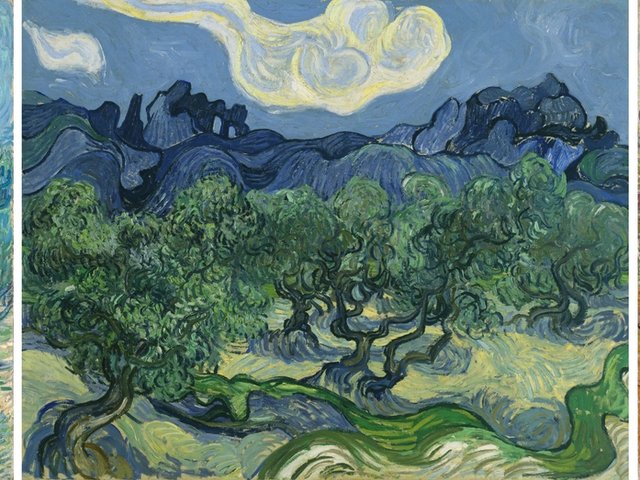

Van Gogh’s Summer Evening (Soir d’été) (June 1888). Courtesy of Kunst Museum Winterthur (gift of Dr. Emil Hahnloser, 1922) (photo: SIK-ISEA, Zurich, Jean-Pierre Kuhn)

The best example of Van Gogh fingerprints is on Summer Evening, painted in Arles in June 1888 and now at the Kunst Museum Winterthur, in Switzerland. As with Olive Trees, the marks are in the centre of the top edge, suggesting that Van Gogh made of habit of carrying his wet canvases in this way.

In Summer Evening, the marks appear to be the thumb and forefinger of a left hand. The painting was done on a very windy day, when the mistral wind was blowing hard, which helps explains why he had trouble holding the canvas, probably after it was off his easel.

As Van Gogh told his friend Emile Bernard about Summer Evening: “I painted it out in the mistral. My easel was fixed in the ground with iron pegs, a method that I recommend to you. You shove the feet of the easel in and then you push a 50-centimetre-long iron peg in beside them. You tie everything together with ropes; that way you can work in the wind.”

Fingerprints have now been discovered on a dozen or so paintings by Van Gogh, and sometimes it is suggested that these could be used to help authenticate his work. However, nearly all the prints represent only part of a finger or are smudged, so this is unlikely to prove a viable means of authentication.

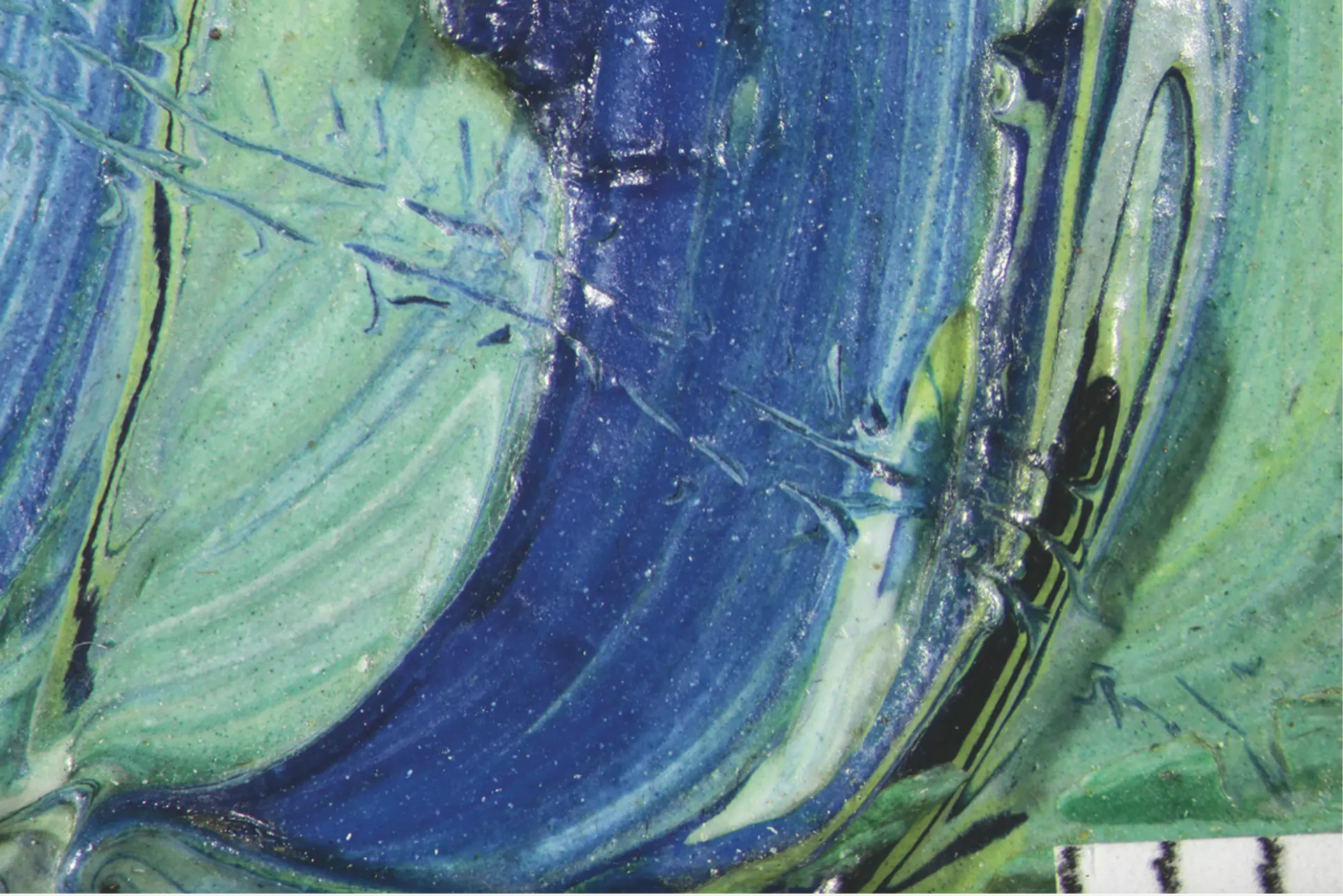

As well as fingerprints, traces of insects have been found on two of Van Gogh’s other olive grove paintings. These were also discovered during research for the current exhibition. On Olive Grove (July 1889, now Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo) an 18-cm trail was left by a small insect which crawled through the artist’s wet paint.

Photomicrograph of an insect walking through the paint, a detail from Van Gogh’s Olive Grove (July 1889). Courtesy of the Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo (photomicrograph: Margje Leeuwestein)

And on another painting, Olive Trees (June 1889, now Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City), the remains of a grasshopper were found. The unfortunate creature was blown into Van Gogh’s wet paint, probably while the artist was working in the grove on a summer’s day.

Photomicrograph of a grasshopper’s head and hind leg on Olive Trees (June 1889). Courtesy of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri

These fingerprints and insect remains give us an added insight into Van Gogh’s way of working. Overlooking minor details of their execution, he was totally focussed on the impact of his paintings.