The art market is one of the many international business sectors that is wondering what is going to happen to its sales figures in 2025 as US President Donald Trump’s wildly unpredictable executive orders—and a whole lot else—disrupt the global economy.

In March the French database Artprice released a report, The Art Market in 2024, which states that last year global art auctions (the only sector of the market with transparent, quantifiable sales data) raised $9.9bn, a decline of 33.5% year-on-year, owing to a “contraction of the high-end market”. It adds that this was the third year in a row that overall auction turnover has declined, shrinking to the lowest level since 2009. On the other hand, the report’s data show that the number of lots sold in 2024 reached a record high of 804,000, with about half of these selling for under $600. Many buyers “took advantage of cheaper purchasing opportunities”, according to Artprice’s report.

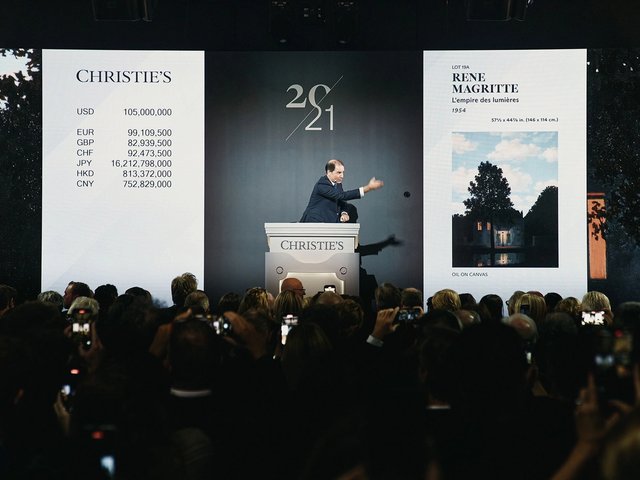

The art market, like most markets, is obsessed with growth. However, record numbers of works selling for under $600 is not the kind of growth that the senior management of auction houses like Sotheby's and Christie’s, or indeed of mega-dealerships like Gagosian or Hauser & Wirth, is looking for.

For many, a key cause of concern is the slump in the prices of big-ticket works by the prestige 20th- and 21st-century names that are meant to underpin the financial and cultural value of this market. So-called “blue chip” art has not turned out to be a surefire investment.

The Financial Times reported in March that leading specialist art finance lenders are making “margin calls” that require borrowers to top up their collateral with cash or more art as the value of the security for their loans has shrunk in the market slump. The FT quoted Scott Milleisen, Sotheby’s Financial Services’s global head of lending, as saying, “There are very few categories where the value of art has gone up in the last 24 months.”

Shrunken blue-chip values were plain to see at last month’s evening auctions of Modern and contemporary art in London.

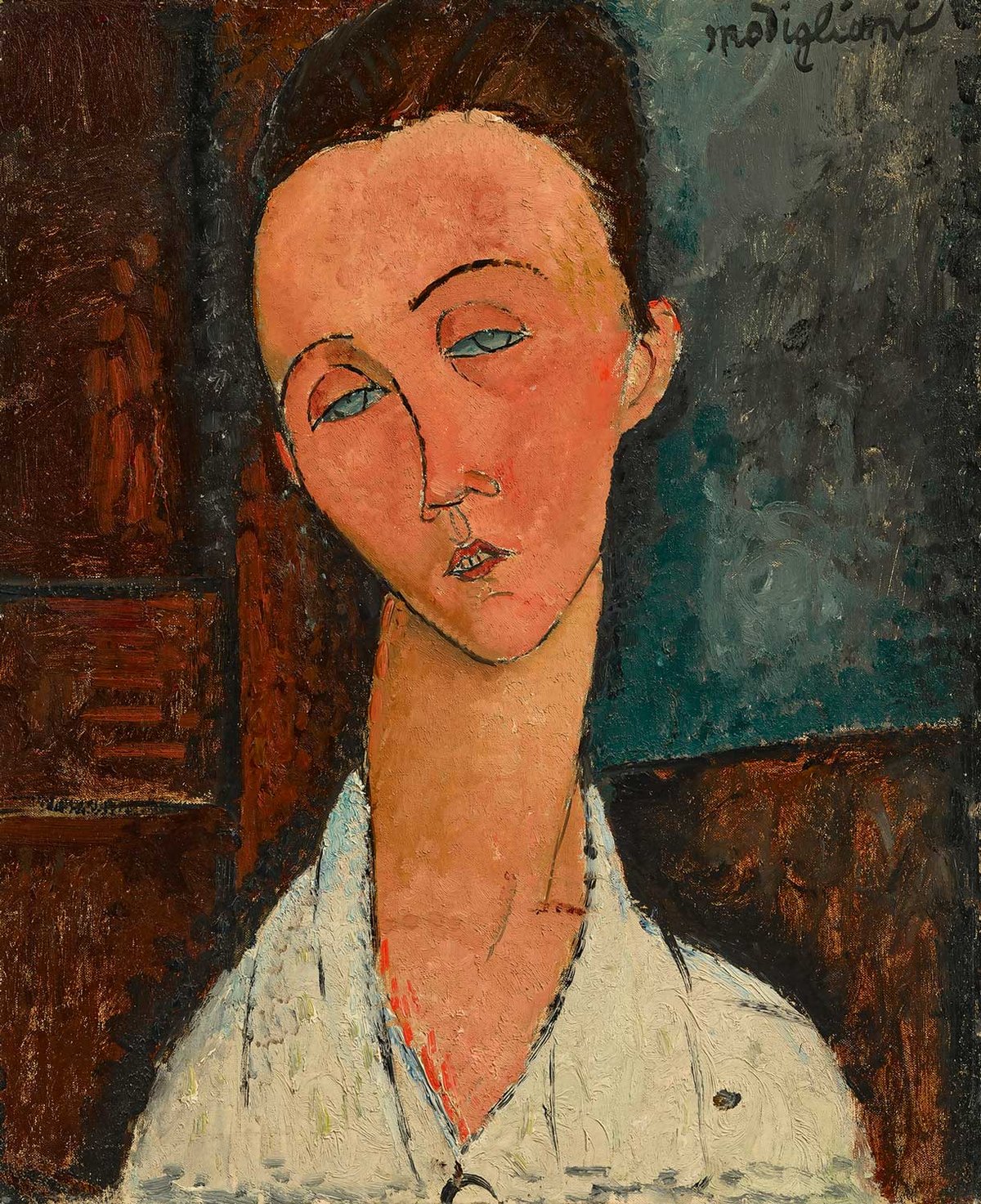

At Christie’s, for instance, Amedeo Modigliani’s archetypal head-and-shoulders Portrait of Lunia Czechowska (around 1917), with a mass of old labels on the back, sold within estimate for £6.3m ($8.1m), with fees. Way back in 2011, Modigliani’s similarly sized, composed and dated La blonde aux boucles d’oreille sold at a New York auction for that same price. Later in the Christie’s London sale, Bridget Riley’s big, vibrant Daphne (1988) made £1.4m (with fees), again within estimate. Riley’s similarly composed and identically sized abstract, Gaillard (1989), had sold at auction in 2020 for £2.3m (with fees).

Of course, there are always individual results that contradict a perceived trend. Sotheby’s London auction of Modern and contemporary works last month included Alberto Burri’s market-fresh 1955 mixed-media work Sacco e Nero 3 that sold above estimate for £4.9m (with fees), the highest auction price for the artist since 2022. A Yoshitomo Nara painting fetched a week-topping £9m (with fees). Yet Sotheby’s seemingly impressive high-estimate total of £62.5m (with fees) for its March evening Modern and contemporary auction in London was a sobering 80% down on the £312m (with fees) it achieved at its equivalent auctions in 2017.

Death, divorce, debt and downsizing

Renewed growth in the global art market in 2025 is contingent on a lot more big-ticket art becoming available, both at auction and through galleries, and a lot more money being spent on it. Falling values might have discouraged discretionary sellers from offering works for sale, but this is the era of the Great Wealth Transfer in which the Four Ds (death, divorce, debt and downsizing) are freeing up valuable collections accumulated over decades by rich Boomers.

In May in New York, Christie’s will offer 30 Modern and contemporary works from the collection of the late Barnes & Noble founder Leonard Riggio, valued at $250m. This includes Piet Mondrian’s, Composition with Large Red Plane, Bluish Gray, Yellow, Black and Blue (1922), estimated at around $50m. Later in the month, Sotheby’s will auction Old Masters from the collection of Thomas A. Saunders III, a former chairman of America’s right-wing Heritage Foundation, estimated at $80m.

“It just needs three heiresses to die and the auctions will be choc-a-block,” says Guy Jennings, a senior director at the London-based advisory, The Fine Art Group.

If, thanks to those Ds, the market’s supply of big-ticket works does pick up, money, at least in terms of its sheer availability, should not be a problem. President Trump’s budget, currently passing through Congress, plans to deliver $4.5 trillion in tax cuts over the next nine years.

“Trump’s proposal to extend tax cuts and deregulation will disproportionately benefit the highest earners, who are the most likely to be buying art at the top level. As such, this could encourage buying amongst this US cohort over the next few months, especially over the next big marquee sales in New York in May,” says Harco van den Oever, the founder and chief executive of the London-based financial advisory, Overstone Art Services. “However, given that multiple other nations participate in the art market, this may be counteracted by wider economic uncertainty on a global scale,” Van den Oever adds.

Trump’s to-and-fro on tariffs

Trump’s erratic imposition and removal of trade tariffs has added to this uncertainty. The London contemporary dealer Ben Brown, who has a gallery in Hong Kong selling Western art, says that America’s punitive 20% import tax slapped on China would not adversely affect his business. “It is only Chinese-made art which will be subject to the tariffs,” he says. The extent to which these tariffs might affect China’s own art market have yet to be assessed. “If European art were subject to tariffs, I would be seriously worried,” Brown adds.

A longer-term concern is what is going to happen to the art market’s collector base. There has been an assumption, or at least hope, in the art trade that once the multimillion-dollar dispersals of the Great Wealth Transfer happen, at least some of the younger recipients of this wealth will be as enthusiastic about buying beautiful paintings, sculptures and drawings as their parents and grandparents were. The collector base will undergo a generational renewal, as it has done for centuries.

But why would wealthy Millennials and Zoomers, immersed in the constantly changing digital culture of Instagram, Spotify and TikTok, find anything relatable about hand-made pictures by long-dead artists like Modigliani and Mondrian, or even Picasso and Richter? Why would you want to spend millions of dollars on such things?

The art-price database Artnet, in a report released in March, says the market has reached a “generational turning point”, in which demand is driven by younger buyers and “luxury, pop culture and digital engagement are shaping collecting habits”. Christie’s much-reported $728,784 online auction of AI-generated art that ended last month has been seen as the shape of the art market to come.

If this analysis does prove to be the case, then the art market will have a serious accounting problem. The price points of digital art remain, at the moment, relatively low (a third of the lots in Christie’s AI art auction sold for under $10,000). There could of course be an explosion of crypto-driven speculation in this kind of art, as there was in 2021, but the numbers generated would still be a fraction of that traditionally spent on big-name 20th-century painting and sculpture. What happens when the critical mass of collectors who bought this older analogue art dies out? Will the value of 20th-century art suffer the same fate as the value of Old Masters? If that is the case, then how can the art market’s numbers grow?

“The art market’s obsession with growth is a relatively late development that wouldn’t have concerned Duveen or Durand-Ruel,” says Guy Jennings, referring to the great taste-making dealers of the Gilded Age. “It’s a function of late-phase capitalism.”

Is the art market a business, like terrestrial television, print media and coal mining, that simply has to get over the idea of growth?