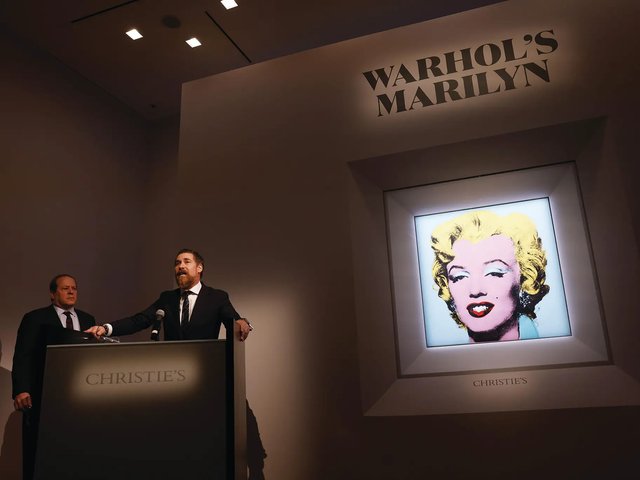

Last month London and Paris hosted in-person international art fairs. New York has recently just held a $2bn, 2,000-lot “gigafortnight” of live auctions. Admittedly there were hardly any American and Asian visitors at Frieze London and Fiac in Paris, and the studio audiences at Sotheby’s, Christie’s and Phillips’s hi-tech evening sales were restricted to select invitees, but the “new paradigm” at the top end of the global art market is nonetheless taking shape.

This first real blockbuster series of auctions in the US since Christie’s $835m Rockefeller sale in 2018 took place towards the end of year during which the 400 richest Americans had seen their wealth increase by 40%, according to Forbes. In addition, UBS reports that pandemic-rebounding asset prices have boosted aggregate global billionaire wealth to a new high of $10.2tn. There are now 2,189 billionaires in the world, 389 of them from China, UBS says. On top of that, the prices of cryptocurrencies have recently hit all-time highs.

Little wonder, then, with all this pent-up wealth at the disposal of the world’s 0.01%, that these New York auctions achieved some big numbers, boosted, at certain points, by live-streamed telephone bidding from Asia.

The choicest 35 works from the long-awaited sale of the collection of the bitterly divorcing New York couple Harry and Linda Macklowe, billed by Sotheby’s as “the most significant collection of Modern and contemporary art ever to appear on the market”, sold on 15 November for $676m (with fees), against a high estimate of $619m (without fees). The top price here was $82.5m for the 1951 Mark Rothko abstract, No. 7, sold to a telephone bidder in Asia.

Christie’s The Cox Collection: The Story of Impressionism auction, comprising 23 pictures from the estate of the Texas oil magnate Edwin Lochridge Cox, was held just when major auction houses had abandoned dedicated evening sales of Impressionist art. This 19th-century material may not be at the cutting edge of today’s collecting taste, but it still raised $332m with fees, well over the $268m high estimate, based on hammer prices. The stand-out result was the $71.3m given in the room by the London-based art advisers Beaumont Nathan for Van Gogh’s 1889 landscape, Cabanes de bois parmi les oliviers et cyprès.

And then there were Christie’s and Sotheby’s newly separated mixed-owner Modern and contemporary offerings. At Christie’s 21st century evening sale, Beeple’s 2021 NFT-yoked kinetic video sculpture of an astronaut walking in a dystopian landscape, Human One—and the bragging rights that went with it—were bought by Ryan Zurrer for $29m. The tech entrepreneur promptly tweeted about his new acquisition, a far cry from the obsessive secrecy associated with the more traditional breed of art collectors.

A full house for Sotheby's sale of the Macklowe collection

Courtesy of Sotheby's

Numbers like these were reminiscent of the boom years of the art market from 2014 to 2018, when aggregate global auction and dealer sales reached an all-time high of $68.2bn, according to the Art Basel & UBS Art Market report. So what is different this time round?

“The market has been frustrated by nearly two years of Covid restrictions, which has decimated gallery exhibitions and art fairs, and made auction the dominant selling platform,” says Hugo Nathan, the co-founder of Beaumont Nathan. “The other key factor is undoubtedly financial, with the effects of quantitative easing etc,” adds Nathan, referring to central banks’ stimulus programmes, which have raised asset prices. “But Christie’s had ‘never-seen’ fresh material, with mega museum calibre works by the biggest names in the market.”

There has also been a shift in taste. These latest New York auctions appeared to reassure the outside world that works by the classic white male names of canonical art history remain a dependable blue-chip investment, despite the speculative multiple-estimate prices being paid at auction for “red chip” works by young artists from more diverse backgrounds, and even giddier numbers for NFTs.

“The Macklowe collection was a time capsule of collecting in the second half of the 20th century,” says Wendy Cromwell, a New York-based art adviser. “Despite the fact that a paradigm shift has occurred, male masters like Johns, Twombly and Rothko are still masters, and still vital to the story of art. Apparently, two paradigms can exist simultaneously.”

The demographic that readily identifies with art from the 1950s and 60s—let alone the 1870s—is dwindling. Christie’s NFT specialist Noah Davis revealed in a pre-auction essay that he told Mike Winkelmann, aka Beeple, that Human One reminded him of Alberto Giacometti’s celebrated 1960 sculpture, Walking Man I. Beeple had never heard of Giacometti.

Beeple's Human One (2021) solf for $29m

Courtesy of Christie's

Both the Macklowe and Cox auctions were celebrated as 100% sold “white glove auctions”, but every lot was pre-sold via guarantees. Sotheby’s and Christie’s had already “bought” these collections, having put at least $600m and $200m respectively on the table to their owners. Then risk was offloaded onto third parties on as many works as possible.

The Macklowe’s textbook Upper East Side taste felt dated in today’s market, and bidding, for the most part, was conspicuously measured, with nothing breaking the $100m barrier. The $82.5m paid for the Rothko, $78.4m for Giacometti’s Le Nez (bought by the Chinese BitTorrent chief executive, Justin Sun) and $58.9m for a late Cy Twombly were all bid within their estimates. Auction records for all three of these blue-chip artists were set at least five years ago. Conversely, Van Gogh, the world’s favourite subject for touring immersive experience shows, seems to be a timeless brand. The three small Van Gogh works in Christie’s Cox sale each attracted up to five telephone bids from Asia. The 1890 portrait Jeune homme au bleuet sold for $46.7m, almost 10 times the low estimate.

Ultimately, for all the importance the auction world attaches to its activities, art remains a niche investment. Looking through the list of Forbes’s richest Americans, it is striking to see how few are prominent art collectors. The value of the S&P 500 index of US stocks has more than doubled since 2014, while overall global art sales have flatlined. For the super-rich, there are far easier ways of accumulating wealth than buying art, which can be subject to onerous costs and taxes, as well as price volatility. A recent investigation by ProPublica journalists reveals that American billionaires prefer to just watch their stocks rise in value, then take out tax-free, low-interest loans against the value of these assets to pay for living expenses.

As the Tesla founder Elon Musk, whose $271bn fortune makes him, according to Forbes, “the richest person in the history of the world”, brazenly admitted on Twitter recently: “I do not take a cash salary or bonus from anywhere…the only way for me to pay taxes personally is to sell stock.”

But back in that other paradigm of the market for emerging art, there are still spectacular, if taxable, short-term gains to be made.

In November, Sotheby’s new-format The Now auction included the 2018 canvas It’s Better Down Where It’s Wetter, by the of-the-moment British painter Flora Yukhnovich. This exuberant riff on 18th-century French rococo painting was estimated at $150,000-$200,000, but to encourage more expansive bidding Sotheby’s cataloguing helpfully included the “market precedent” of the £2.3m paid for Yuknovich’s I’ll Have What She’s Having (2020) in London in October. The tactic paid off, with the work achieving $1.8m (with fees).

“There’s an optimism and beauty in her work that really grabs people,” says Matt Watkins, the co-founder of London’s Parafin gallery, which until earlier this year represented Yukhnovich, who has since moved to Victoria Miro. Large-scale paintings at Parafin’s breakthrough 2019 show of Yukhnovich’s work were snapped up then for about £30,000.

The British Government Art Collection acquired Yukhnovich’s Imagination, Life is Your Creation from that show. This splash of rococo now looks a treat hanging in 11 Downing Street, the choice of Rishi Sunak, the chancellor of the exchequer and husband of the Indian billionaire, Akshata Murthy.

The 21st century’s new paradigms can sometimes have a distinctly pre-revolutionary, 18th-century feel.