Popular digital artists of our time whose works dominate social media, such as Beeple, often depict a bleak, dystopian, soulless version of the coming century. From the series Black Mirror to the Jennifer Lopez action film Atlas, the majority of movies and television shows dealing with artificial intelligence (AI) and technology frame the current and coming advances of technology as malignant. The recent reboot of Dune by Denis Villeneuve, the highest-budget big-screen imagining of the future in a long time, is largely devoid of color, presenting a hazy, dusty and stylistically de-saturated take on the 11th millennium.

These bleak and flavourless visions of the future make it all the more refreshing to visit the first significant posthumous exhibition in New York devoted to Syd Mead (1933-2019). An industrial designer who started making concept art for films when he was in his forties, Mead is responsible for defining what the future was supposed to look like for many Baby Boomers, Gen Xers and Millennials. He defined the aesthetics of iconic films including Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979), Blade Runner (1982) and Tron (1982), and his paintings in Future Pastime (until 21 May), an exhibition curated by Elon Solo and William Corman in the former Mitchell-Innes & Nash space in Chelsea, make it clear that he has inspired plenty of film-makers since.

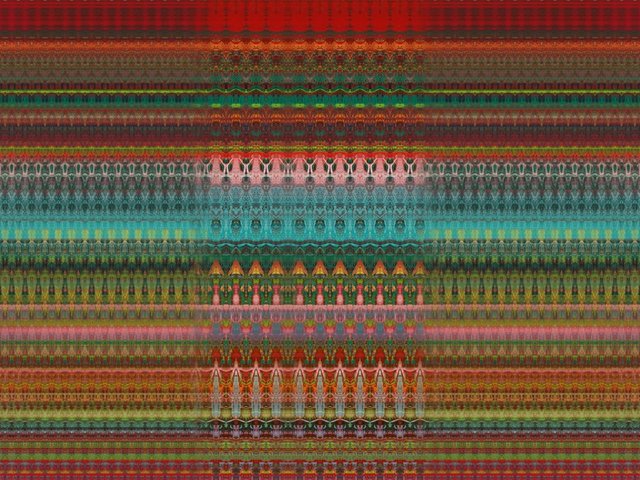

Syd Mead, Cavalcade to the Crimson Castle, 1996 Courtesy Syd Mead Incorporated

Science fiction in the 1970s and 80s had a sensuality that has since become neutered, with studios opting for a more child-friendly, sanitised approach to character and world-building. Mead not only invented future vehicles, social spaces and technologies, but infused them with texture and mystery. He designed Star Trek: The Motion Picture’s chief antagonist, the V’ger, as a gargantuan spacecraft that is simultaneously phallic and yonic.

Mead was hired to design the flying police vehicle for Ridley Scott’s sci-fi classic Blade Runner, which made sense as he had made his name as an industrial designer creating concept art and advertising visuals for car, tire and steel companies. But his need to situate the flying car in a universe where it belonged snowballed into a holistic design for the dystopian, neon-hued Los Angeles of the film’s imagined 2019, dominated by Mayan revivalist architecture where magenta and cyan lights cast complex shadows across a dark urban landscape.

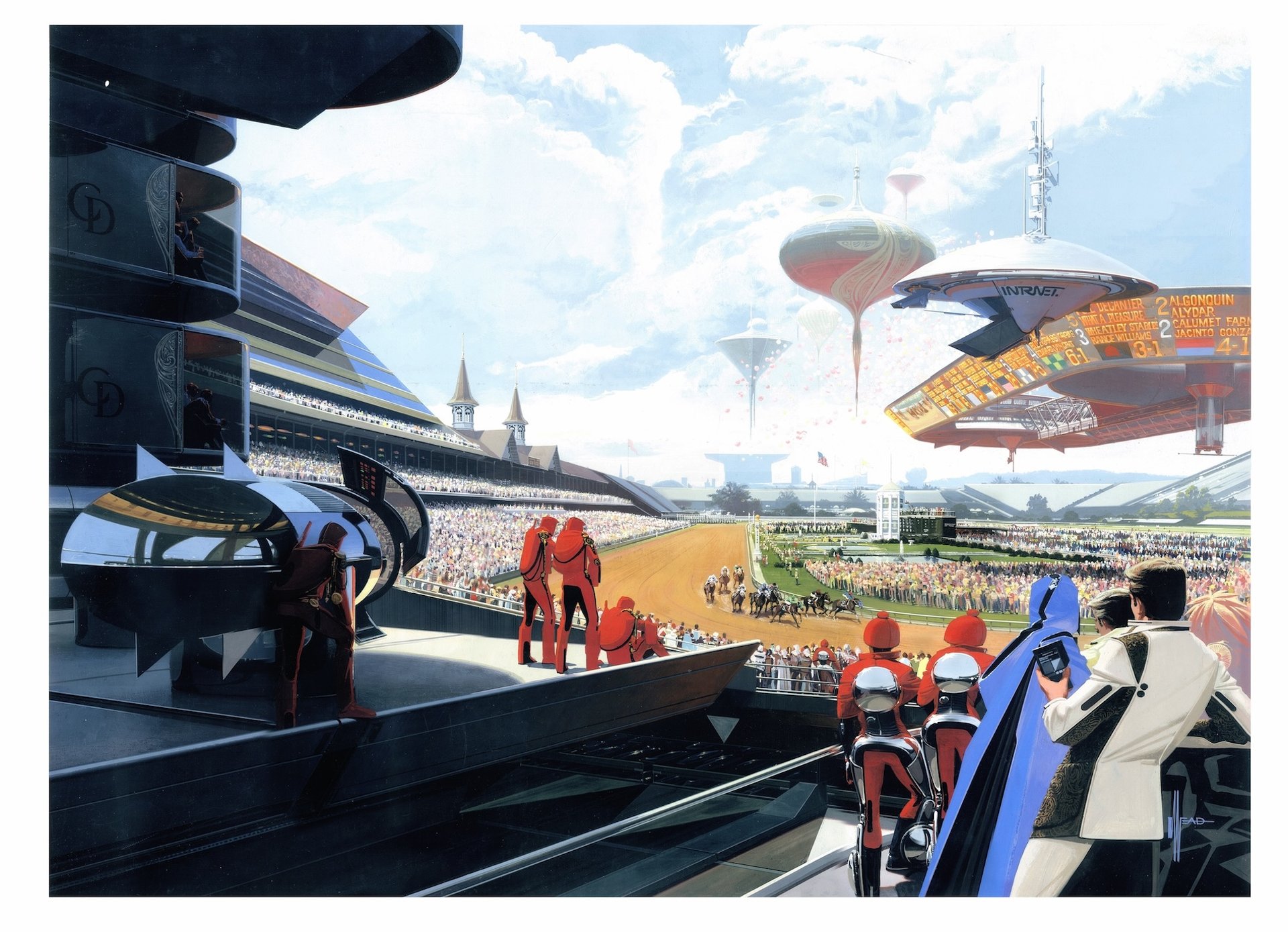

Syd Mead, Running of the 200th Kentucky Derby, 1975 Courtesy Syd Mead Incorporated

In Mead’s art, the architecture of the future is glossy and smooth, brought to life by his medium of choice, gouache. The paintings often feature curvy, chrome, futuristic vehicles, distant megalithic skyscrapers and alien vistas, embracing a kind of futurism that does not associate technology with evil or corruption, but rather with optimism. The influences of the American jet age are omnipresent in his works, but there is a loving sensuality to them, even when he is imagining the future of a historic horse race, as in The Running of the 200th Kentucky Derby (1975). From the way the spectators are grouped and interacting with one another—anonymous, intimate and expectant—it is clear this is a take on the future that believes in leisure and hedonism. The ubiquitous chrome textures in his paintings often reflect parts of the scene that should exist behind the viewer or beyond the frame, enveloping the audience in his luxurious vision of the future and demonstrating his commitment to world-building.

One of Mead’s subtler futuristic inventions can be found in Party 2000 (1977), which depicts a moody club scene filled with people holding "sensation-enhancing" metallic rings in lieu of drinks. This painting, paired with others such as Cavalcade to the Crimson Castle (1996), establish that Mead’s vision of the future was queer. From the humans and humanoid figures’ taught musculature to the graceful manner in which they walk, recline and dance, Mead's choreography of forms have an implicit queerness. While the sensuality of the imagery in almost all of the paintings will resonate for queer folk, they do not necessarily read as queer if one approaches the paintings strictly from a place of fascination with futuristic vehicles and the space age. In a way, it is the perfect kind of visibility for a gay artist who had been painting these scenes since the 1970s.

Syd Mead, Tokyo Bay Boat Race, 1983 Courtesy Syd Mead Incorporated

This is the artist who designed the sexy light-cycles that have defined the Tron franchise, which in turn inspired the motorcycles in Akira. A similar futuristic motorcycle is present in Monster Bike (2004), and along with works such as Running of the 200th Kentucky Derby and Tokyo Bay Boat Race (1983), Mead crafted a leisurely future in which spectacle sports dominate social life. If the track in Running of the Six Drgxx (1983), featuring giant robotic greyhounds, reminds you of the pod-racing track from Star Wars: The Phantom Menace (1999), you are not alone.

Perhaps due to a perception of his practice as commercial rather than fine art—or because he did not see himself as a fine artist either—Mead never became a household name. As Future Pastime continues its multi-city itinerary and people discover the man responsible for their vision of what the future was supposed to look like, that will inevitably change.

As our reality grows stranger than (science) fiction with each passing day, it may feel like all we can ask of the future is for it to be reasonably stable and liveable. Mead reminds us that we can ask for it to be smooth, shiny, leisurely and sexy, too.

Syd Mead, Running of the Six Drgxx, 1983 Courtesy Syd Mead Incorporated

- Syd Mead: Future Pastime, 534 West 26th Street, New York, until 21 May

- A related series of film screenings, Syd Mead: Illustrating the Future, runs at Metrograph, 7 Ludlow Street, New York, until 27 April