In 1991, Gerhard Richter visited Japan with the idea of making a film of his ongoing work, Atlas. When Hans-Ulrich Obrist inevitably quizzed him about the unrealised project a few years later, Richter made a startling admission: he'd gone about things all wrong, he said. He'd been careless in his experimentations. "Film is not for me."

Sit through the 36 minutes of Richter's latest work, Moving Picture (946-3) Kyoto Version (2019–24), currently on show at Gagosian's Roman outpost, and you'll be glad that he paid himself no mind. Now firmly in his ninth decade, the German master has collaborated with filmmaker Corinna Belz, composer Rebecca Saunders and the Dutch trumpeter Marco Blaauw, to make what might just be the crowning achievement of the intervening three decades of work.

On opening night, this restless effervescence of almost impossible detail holds a moneyed, vernissage crowd completely spellbound in the way only a magician might. And that is before the actual performance, wherein the film is accompanied by a live performance of its 13-channel spatialised soundtrack.

Projected at monumental scale, over 7m across, Moving Picture (946-3) is an immersive experience. Initially, Blaauw explains, they resisted the idea of the sound being recorded at all. They wanted it to be a live experience through and through.

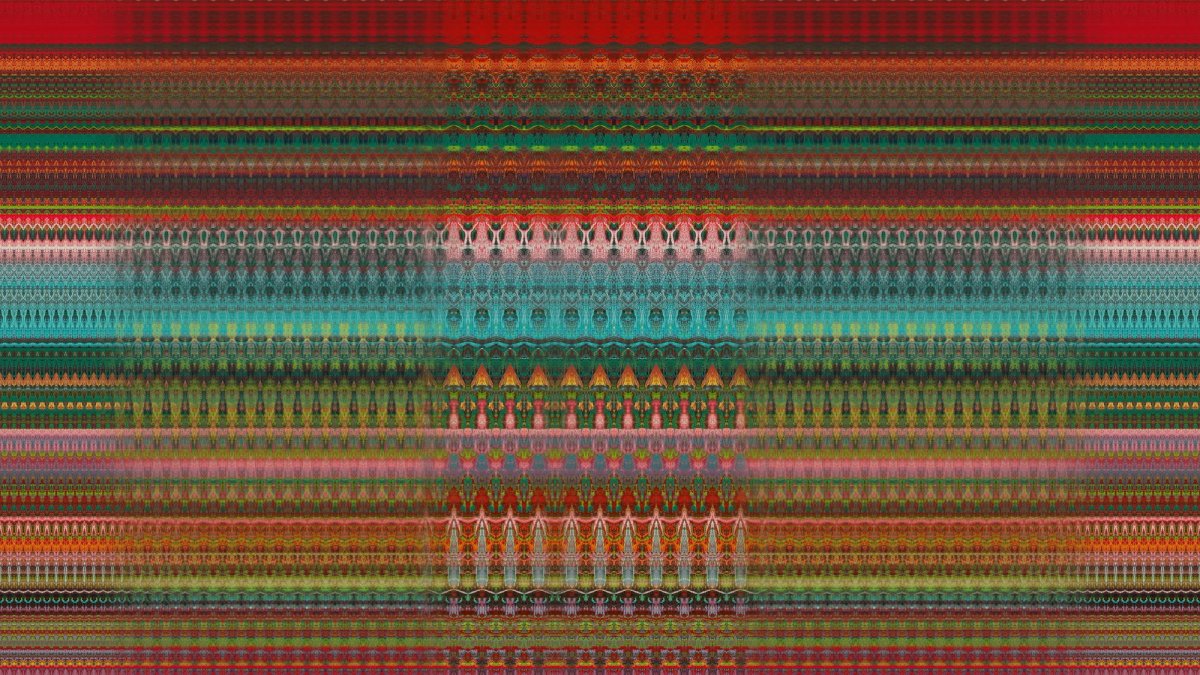

The piece is woven from up-close photographic details of a single Richter piece—Abstract Painting 946-3, from 2016. This is one of the more deeply colourful in the series. Reds, ruby and pomegranate flood the canvas to the right, aquatic greens and blues lurk beneath the surface on the left and from its centre, corn and butter yellows explode in fits and sunbursts.

Moving Picture (946-3) Kyoto Version, 2019-24 (still)

© Gerhard Richter 2024 (28102024). Courtesy the artist and Gagosian

Starting with a digital photograph of the painting, Belz—Richter’s filmmaker collaborator and the only person ever allowed to film him at work—devised a kind of algorithm for progressively breaking it down ever further, to nearly pixel level. This involved halving then mirroring, like a Rorschach test, each photograph and repeating that process. An ever finer symmetrical patterning ensues. The fragments get narrower and more multitudinous as Belz's camera seeks out the galaxies contained within.

On screen you can see these shimmering folds rippling outwards, on the horizontal, from the vertical centre line. There are fades and blurs, overlays and scrapings. At times, everything shimmers. At others, it's like the sun moving in and out of racing cloud cover, or that feeling you get in a spring garden in bloom. The piece breathes you in.

Conversations between visual and audio

Music has always been important to Richter: his candle paintings featured on Sonic Youth's 1988 landmark album, Daydream Nation, the cage paintings he made in the early 2000s were created while listening to John Cage, and his first filmic exploration of Abstract Painting 946-3 was scored by Steve Reich. In Moving Picture there are constant shifts between quiet and noise—both auditory and visual.

Saunders, a composer who has worked for a long time with Blaauw, makes superlative use of his special double bell trumpet to create a score of great swathes of tone and texture. Long single notes chase even longer resonances, with a reverb modelled on the very peculiar acoustics of the mausoleum Norwegian painter Emanuel Vigeland built for himself in 1926 in Oslo. It takes any sound in that room 14 seconds to fade away, an especially long decay time.

Blauuw's echoing trills and flurries give your eyes purchase within Richter's image: you notice specifics, you follow lines, your mind starts identifying motifs, you look for clues. Blaauw’s score chimes, visually, with the images on screen—a whole lot of horizontals, improvised runs notated as squiggly lines, exciting breaks and changes.

Richter apparently wanted the audio elements of this work to be on an equal footing with the visual. The conversation between the two is precisely what keeps an audience paying such close attention.

Moving Picture (946-3) Kyoto Version, 2024, installation view

Photo: Matteo D'Eletto M3 Studio. Courtesy the artist and Gagosian

Some close ups are more obviously painterly than others, showing the kind of marks one might attribute to a painter's hand at work. So too, some stretches of sound wherein the breath and finger work of the trumpeter is dominant. And then both artists' presences dissolve into a purer abstraction, the kind Richter has likely been chasing this whole time.

When the film's palette reddens, the room and everything in it reddens too, a blushing of the light. Multiple people gasp in the glowing quiet. Those moments resonate with La Monte Young's Dream House, with Rothko's Chapel, with Monet's Waterlilies as installed in their special room in the Orangerie in Paris. That's exactly the kind of space this piece deserves—a room all its own, a haven to sit and dream in.

- Moving Picture (946-3) Kyoto Version is at Gagosian, Rome, until 1 February 1 2025