In what way is it useful to think of the late great American film director Stanley Kubrick (1928-99) as an artist? I do not just mean in terms of his films but in considering the fine art influences on him, the material he generated as part of his modus operandi and that which has been developed in response to him: the touring exhibition of his artefacts (including at London’s Design Museum in 2019), art shows inspired by his work—Daydreaming with Stanley Kubrick at Somerset House, London in 2016 featured the artists Gavin Turk, Sarah Lucas, Mat Collishaw, Haroon Mirza and Anish Kapoor—and the beautiful books about his films, such as Taschen’s 2009 limited edition on the unmade epic Napoleon.

Kubrick was clearly engaged with art forms and other artists, not least his wife Christiane who was a painter and whose works often featured in his movies. The influence of art is most evident in the 1975 costume drama, Barry Lyndon which made much use of paintings from the 18th century (notably by Hogarth, Gainsborough and Reynolds). But less is known about how it affected his other films. With two new books focusing on his 1980 horror masterpiece, we now have a good chance to answer this question.

Back in 1966 Kubrick said he would “like to make the world’s scariest movie”. The result, some 14 years later, would be the hugely influential The Shining, which follows struggling writer Jack Torrance (Jack Nicholson) as the winter caretaker of a remote hotel, with increasingly disturbing and ultimately disastrous consequences for him and his family. Whether it is the scariest movie in the world is up for debate, but it has certainly touched many films in its wake.

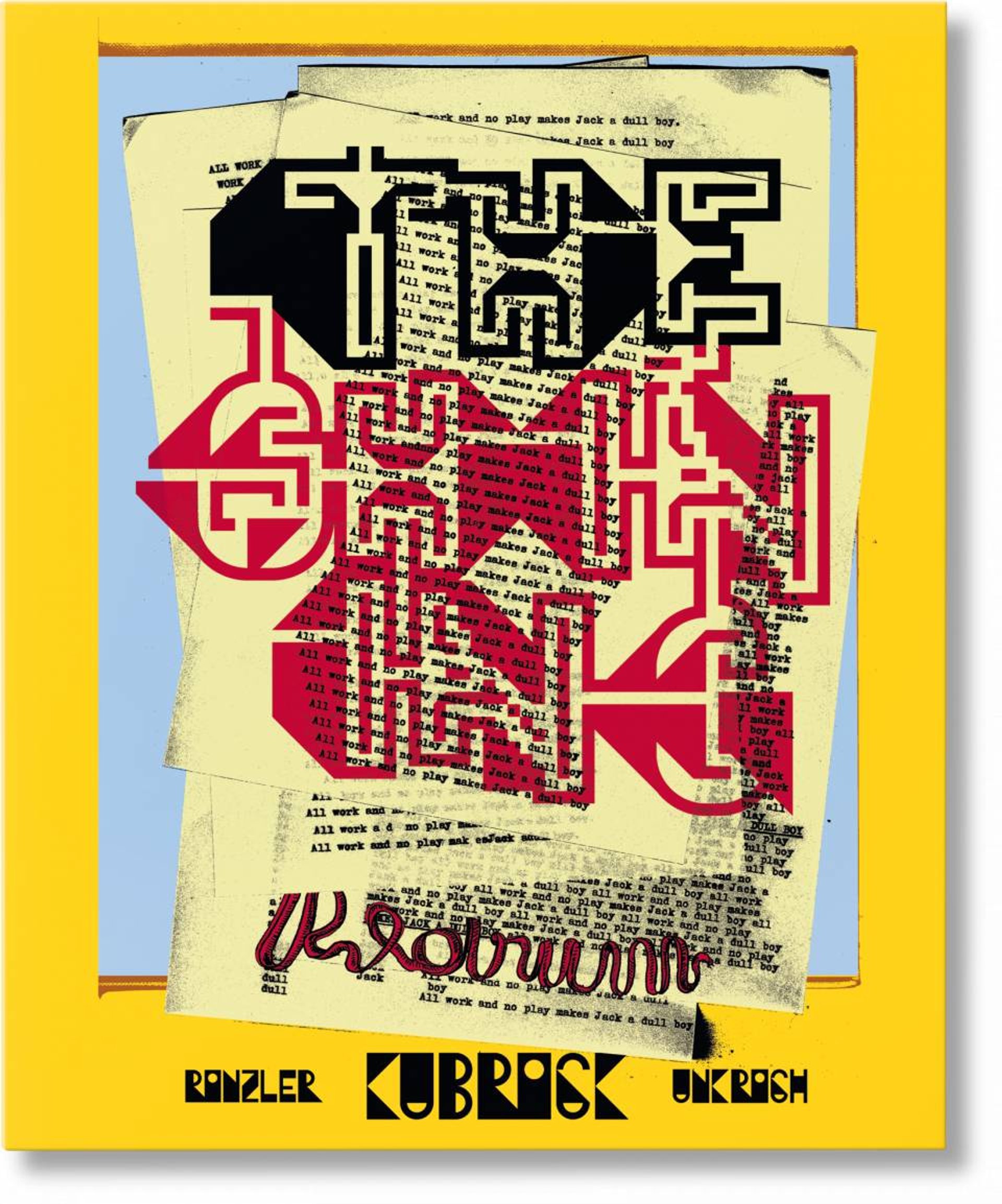

Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (Collector’s Limited Edition) by J.W. Rinzler and Lee Unkrich, Taschen

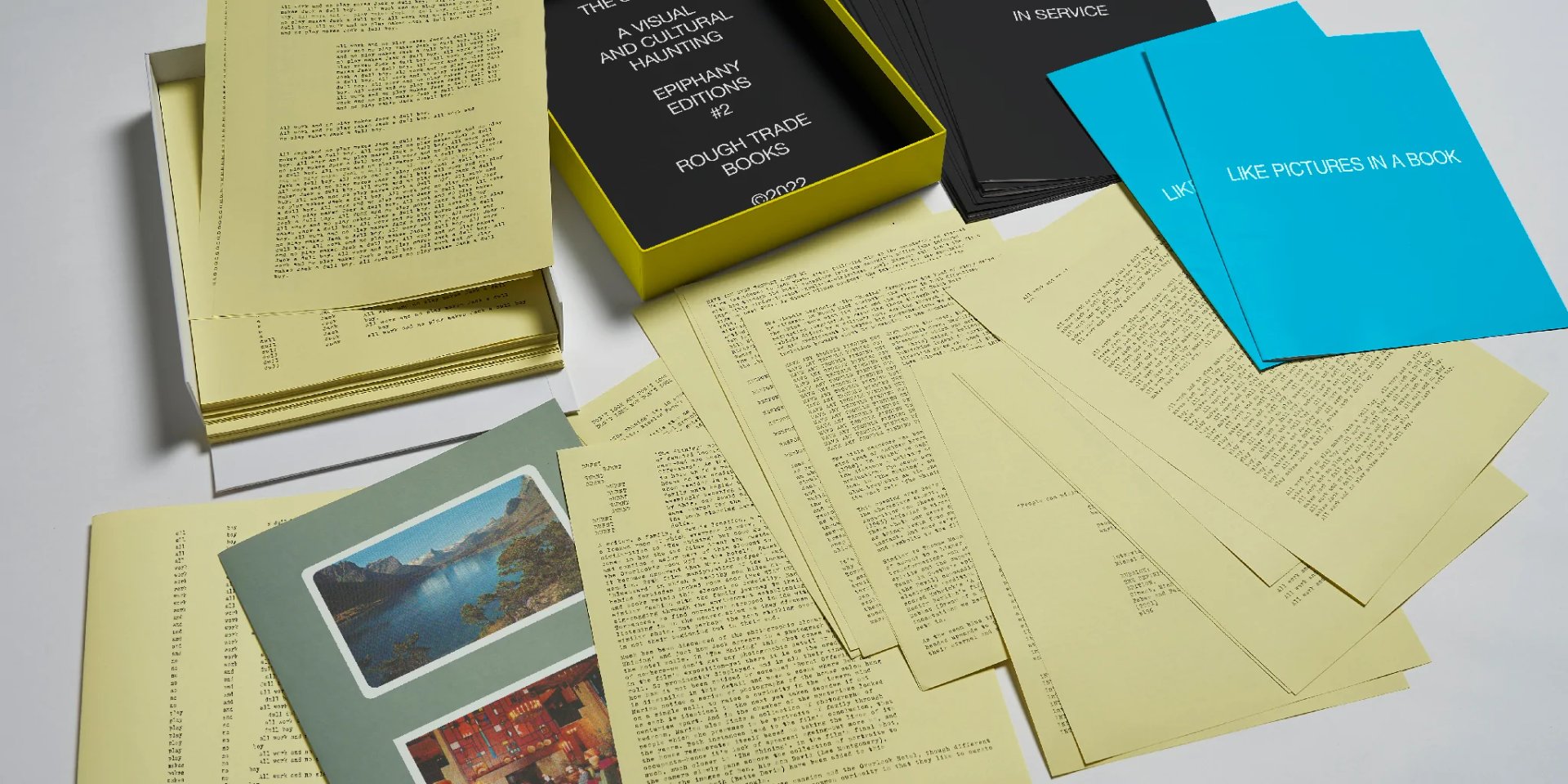

In Taschen’s book, Lee Unkrich and Jonathan Rinzler set out to tell the definitive story of the making of the film, while Craig Oldham’s artefact with the subtitle “A Visual and Cultural Haunting” bills itself as an “immersive, multi-dimensional examination”. Between them, these publications are certainly comprehensive, the product of near-exhaustive research.

The section in Rinzler and Unkrich—a book-within-a-book—entitled “The Making of Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining” is almost 900 pages long and filled with information and images, some of which have never been published, including many not seen outside of the family of Danny Lloyd, the child actor who played Danny Torrance. Oldham, meanwhile, explores the film’s cultural legacy on music, art, mythology, fashion and gender through essays by such cultural luminaries as Cosey Fanni Tutti, Margaret Howell, James Lavelle, Gavin Turk and John Grindrod.

Millais to Goya

Both books illustrate Kubrick’s legendarily rigorous research, which influenced the director as he adapted the source novel. Art certainly played a key role in visualising The Shining, which is replete with references to the work of Alex Colville, Francisco de Goya, Agnes Denes, Carl Andre and more. Oldham includes an intriguing booklet of diverse images, from John Everett Millais’s Ophelia to Goya’s Saturn Devouring His Son, alongside lines from the film demonstrating the clear connections between those paintings and shots and concepts in the film.

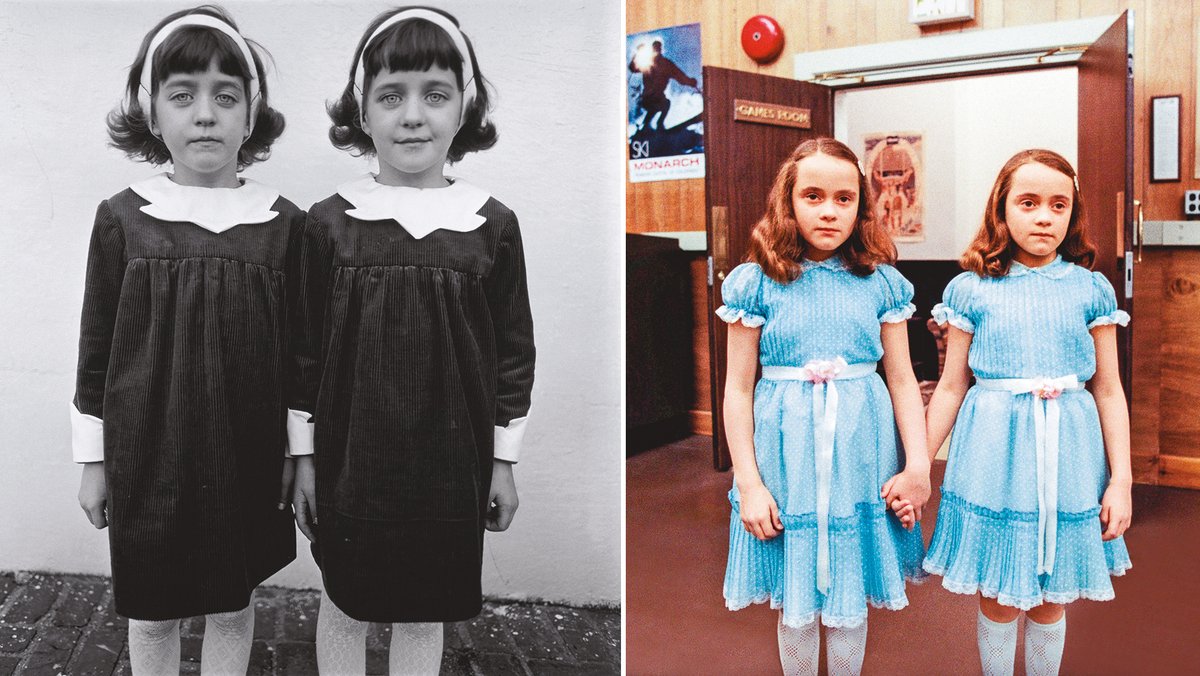

To take one example, in 1972, Kubrick’s assistant Leon Vitali showed him a picture taken from the catalogue of the New York Museum of Modern Art’s Diane Arbus retrospective. Kubrick had known Arbus, who became his mentor when he was working as a rookie photographer for Look magazine in late 1940s. “There was this picture of these two little girls,” Vitali recalled. “I thought, ‘My God, who could ask for better?’”

The Shining: A Visual and Cultural Haunting edited by Craig Oldham, Rough Trade Books

Kubrick reproduced a psychologically dark and uncanny memory of that Arbus photograph Identical Twins, Roselle, N.J., 1966 in his casting of the Grady sisters in the film. In Stephen King’s book on which the film was based, the sisters are not twins. By recasting them as twins, Kubrick introduced the notion of the doppelganger—a theme that runs throughout his work—but also, it has been argued, Josef Mengele’s notorious twins experiments at Auschwitz. Arbus herself was interested in Goya after seeing the Spanish artist’s work and The Shining also quotes his The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters.

Both publications are richly illustrated and contain a wealth of ephemera: photographs, concept designs for the poster and sets, postcards, scripts and the like. They are housed in boxes mocked up to resemble the pages that Jack Torrance types in the film. Indeed, the Oldham artefact is not a book in the conventional sense but rather a series of unbound loose-leafed pages and booklets. While a great deal of material here will be familiar to scholars, for those who have not visited the Stanley Kubrick Archive (at the University of the Arts London) both volumes are a handy one-stop immersion. Like the movie they explore, they can even be considered works of art in their own right.

• Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (Collector’s Limited Edition) by J.W. Rinzler and Lee Unkrich, Taschen, box with 3 vols, 2,198pp, 2,000 illustrations, £1,500, published 14 December

• The Shining: A Visual and Cultural Haunting by Craig Oldham (ed.), Rough Trade Books, box with loose leaf papers & booklets, 400 colour & b/w illustrations, £50/Overlook edition £70, published 10 October