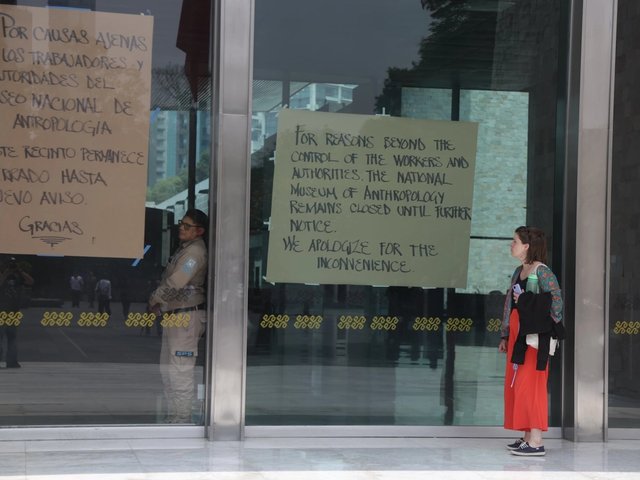

On a crisp morning in January, tourists lined up by the dozen outside the Museo Nacional de Antropología (MNA) in Mexico City. As they waited in line to access one of the most-visited museums in the world—3.7 million visitors in 2024 according to Mexico’s Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH), which manages the museum—they eyed the labour union banners canvassing the entrance. “In defence of cultural heritage, which gives us historical unity and national identity,” read one in Spanish; another declared: “No to the destruction of the INAH. No to the continuity of Diego Prieto and his team. Yes to dialogue: for the better future of the INAH.”

On 6 January, Prieto, the INAH’s director, smiled next to Mexico’s President Claudia Sheinbaum during the re-inauguration of the museum’s ethnographic galleries, representing the country’s living Indigenous heritage. Under floodlights, members of the cabinet, military leaders and artisans from Indigenous communities applauded the purported completion of the galleries’ reinstallation, identified as a key achievement of Sheinbaum’s first 100 days in office. Claudia Curiel de Icaza, the culture secretary, went so far as to claim: “The identities of Indigenous and Afro Mexican communities are for the first time integrated and included in the narrative of a museum such as this.”

The declaration was premature. More than two months after the re-inauguration, most of the new displays still lacked basic didactic labels, leaving the newly commissioned works by Indigenous and Afro-Mexican artisans unattributed. Fire hydrant signs have fallen off. Electrical wiring is visible through a fist-sized hole beneath a mural by the British Mexican artist Leonora Carrington. And tourists from around the world stream through the cavernous galleries like schools of fish without being able to read any of the new section labels, which are printed only in Spanish.

A mural by Leonora Carrington in the recently re-inaugurated ethnographic galleries of the Museo Nacional de Antropología Edgar Alejandro Hernández

The reinstallation is an unfinished project. Approximately half of the galleries, which were inaugurated in 2024 during the last presidential administration, have labels, signage and functional didactic displays. Not so the newer half, where more than one video display is switched off, while antiquated and inaccurate dioramas have no interpretative information. The impression is one of frenzied improvisation, begging the question: why did the president hold an inauguration for an unfinished endeavour?

A delayed project

When it was first inaugurated in 1964, the MNA’s two-storey open plan layout was an innovation in museum interpretation. Its first floor, dedicated to archaeological artefacts from Mesoamerican cultures, was also visible from the second floor, where didactic displays presented a collection of ethnographic objects intended to illustrate the lives of Mexico’s Indigenous communities, grouped by geographic region. At the time—the height of Mexico’s so-called “perfect dictatorship” by the Party of the Institutionalised Revolution (PRI)—those communities were perceived as vestiges of the past, fated to disappear in the face of modernisation. The MNA’s messaging and imposing architecture became key to the PRI’s construction of Mexico’s modern national identity, founded on the idea of mestizaje, a shared and complete hybridisation of Spanish and Indigenous cultures.

By the 1990s, when Mexico began the twin processes of democratisation and integration into global markets, this sense of Indigeneity as belonging exclusively to the past began to lose favour. The EZLN (Zapatista Army of National Liberation) uprising put Indigenous issues squarely in the spotlight, and the MNA began to plan a full-scale revision, which it completed in the early 2000s while conserving the gallery arrangement by region. This era, lasting from 1994 until 2018, is now referred to as the “neoliberal period” by the leaders of Morena, the populist, nationalist movement in power today, under whose aegis—during the presidential administration of Andrés Manuel López Obrador (2018-24)—the MNA’s ethnographic galleries were reorganised into their present form.

A display of masks in the revamped ethnographic galleries of the Museo Nacional de Antropología Edgar Alejandro Hernández

When the project is truly finished, perhaps visitors will be able to evaluate how the new curatorial script improves upon the discarded regional layout, which did not give space to Afro Mexican communities, for example. The new arrangement is instead thematic and organised into five sections: histories, identities and resistance; peoples, languages and territories; maize, milpas, land and nourishment; textiles; and celebrations and rituals. Funding came from López Obrador’s flagship culture project, Chapultepec Forest: Nature and Culture, whose total budget ballooned to 10bn pesos ($486m) by the end of his term. A request for government information from 2023 revealed that each of the first two gallery sections inaugurated last year and devoted to textiles and celebrations and rituals was budgeted at 14m pesos (around $680,000), suggesting the full cost of the project may have stretched to 70m pesos ($3.4m), an eye-watering amount for museum operations in Mexico. The funds were managed by the INAH’s National Office of Museums and Exhibitions, under Prieto’s jurisdiction, and not the director’s office at the MNA. None of Chapultepec Forest’s initiatives were delivered on time.

A hollow sense of national identity

Since being sworn in last September, President Sheinbaum has had to finish, correct or repair several of her predecessor’s pet projects while remaining in lockstep with Morena’s populist rhetoric and principle of so-called “republican austerity”. The cultural front is no different: all of her administration’s policies have sought to distance her agenda from the so-called “neoliberal governments of the past” and brandish a sense of nationalism that capitalises on Mexico’s ethnic diversity, in opposition to the myth of mestizaje that is today denounced as a rigid assimilation policy. According to a statement by a spokesperson for the ministry of culture: “This reinstallation represents the best way this museum [and the INAH] can renew its commitment to the cultural, political and social plan of Mexico’s government, most recently upheld by Congress through the constitutional amendment which reaffirms that Indigenous and Afro Mexican peoples are deserving of civil rights.” The statement makes plain the MNA’s instrumentalisation by a political party that has strengthened the military and bulldozed the judicial branch, while proclaiming itself a torchbearer for ethnic and racial equality.

A display case in the recently re-inaugurated ethnographic galleries of the Museo Nacional de Antropología in Mexico City Edgar Alejandro Hernández

A visit to the galleries confirms the reinauguration event was all style and no substance, and that the reinstalled displays take serious liberties in how they portray Indigenous heritage. For instance, in the “histories, identities and resistance” section, a video includes clips from two fiction films dating to the Golden Age of Mexican cinema (1936-56), in which superstar actresses of the era Dolores del Rio and María Félix—neither of them Indigenous—play Indigenous roles. The video also includes shots from documentary films about Indigenous communities. There is no information to explain the distinction between fact and fiction, or the construction of “the Indian” for public consumption in contrast to ancestry, belonging and ritual. This problem is repeated throughout the galleries, where facsimiles and replicas are often displayed beside original artefacts. Visitors have no information and no tools to tell documentation from fiction, or original expressions from facsimiles.

“The official act of the inauguration was planned by the presidency and the secretariat of culture, the federal authority to which the INAH and MNA belong,” says Antonio Saborit, the MNA’s director. The incomplete state of the installation—Saborit says he expects wall labels and other didactics to be finished “in the next few months” and English labels to take the rest of the year—and the conspicuous signs that the museum’s specialised work force opposes the continuance of Diego Prieto’s leadership of INAH suggest the MNA’s ethnographic galleries were inaugurated solely for political gain. As occurred with Morena’s constitutional amendments earlier this year, the party cared more about imposing its ideological tenets than how the results and the means by which its political victory was achieved might harm public institutions and their international standing.

A life-size diorama in the newly refurbished ethnographic galleries of the Museo Nacional de Antropología in Mexico City Secretaría de Cultura

President Sheinbaum used the ethnographic galleries’ reinstallation to stage a political event that would not only give closure to one of her predecessor’s projects—Chapultepec Forest’s expenditures went well over budget and lacked transparency—but also position her as successfully delivering on all matters of public administration, which in Mexico includes culture. The secretary of culture’s self-congratulatory tone when noting the inclusion of Afro Mexican communities appears all the more spurious given that it is precisely the vitrines with Kente cloth, African helmet masks and Akuaba dolls that lack basic labelling identifying the artifacts, their origins and their importance to Mexican cultural diversity. The opportunity to learn about these communities and their contributions to national heritage has been lost for the tens of thousands of visitors who have already passed through the incomplete galleries.

Based on what is today available on the museum’s second floor, Indigenous and Afro Mexican communities remain sadly absent from the MNA’s curatorial script, as a visitor will not be able to identify them, recognise them or even tell them apart from fictionalised versions in movie excerpts. The fanfare surrounding the ethnographic galleries’ re-inauguration served one purpose only: to trumpet the new administration’s pride in a string of dubious achievements while strengthening a political movement that has trafficked in identity politics to stoke nativist sentiment and win votes. The INAH’s workers picketing outside the museum in January said it best: may there be a better future at the MNA, in which cultural heritage is valued and defended for its own sake.