My First Experience in an English Country Pub (“The Blinkin’ Bull”), Aubrey Williams’s satirical poem, datable to around 1952, is among the many revelations in Aubrey Williams: Art, Histories, Futures, the first monograph touching on the full range of the artist’s practice. Alongside artworks, many photographed for the first time, are diaries, archive photographs and, surprisingly, portraits of Fidel Castro, Che Guevara and Inca bodies liberated from the pages of National Geographic.

The contrast between the fine, precise detail of Williams’s writing, including his poetry, and his better-known abstract paintings is thrilling. The editors have in the main separated the two, privileging his academic writing. But the best sections are where these media are placed together in conversation, suggesting connections in the artist’s thinking and practices.

Exploring environmental destruction

Williams disrupted Western/European perspectives of linear time: as evident in his membership of the Royal Astronomical Society as in his interests in ancient mythology. The text highlights how timehri (indigenous petroglyphs from the Caribbean) and pre-Columbian Warrau (Waroa) signs often featured in Williams’s cosmic representations of British landscapes. Connecting these postcolonial environments, of his birth and his adult life, Williams often explored the environmental and ecological destruction inherent in empire’s projects, an awareness rooted in lived experience and his early training as an agricultural officer in Guyana in the early 1940s.

Williams (1926-90) is now considered an artist ahead of his time, a position reflected in monographic exhibition titles like Future Conscious in 2023. The text here illustrates how this is neither an anachronism, nor a case of reading the artist in the light of today’s climate crises. In the provocatively titled article, “Why Isn’t This Artist Hanging in the Tate?” (1985), Guy Brett, the celebrated art critic and curator, reflected how Williams’s works addressed “an ‘eco-crisis’ of planetary proportions”. It was penned in response to an exhibition of the same year, The Olmec-Maya and Now, held at the Commonwealth Institute in London, which served as a warning against repeating the apocalyptic fate of Classic Mayan societies, and an exercise in caution about the use of technology for the over-exploitation of the Amazon rainforest.

Beyond abstraction, the text reveals Williams’s interest in beings other than human. Frogs, which feature on the pots of Eve Williams, the artist’s wife, also photographed for the first time, recur as motifs; birds too. The Caribbean Artists Movement, with its journal Savacou—styled after the Carib bird-god, Sawaku—is often referenced, constellating with other research, exhibitions, and publications nationwide on Ronald Moody, Althea McNish, John Lyons, Gavin Jantjes and, more recently, Hew Locke.

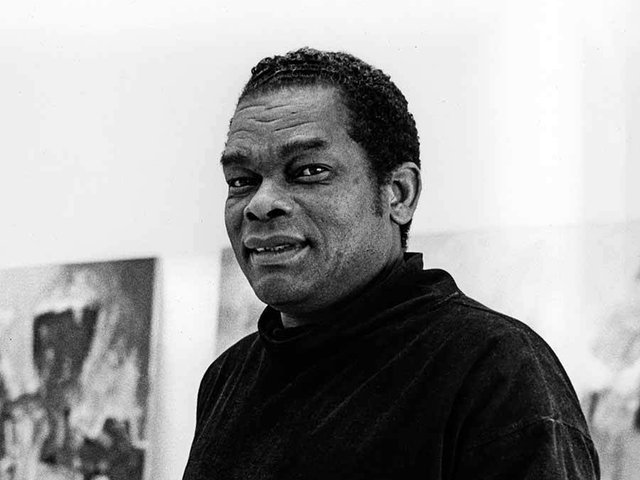

Williams, posthumously, has become a ubiquitous presence in London, with important displays at Tate Britain, the Barbican and Spotlight section of the 2024 edition of Frieze Masters. Less commonly, though, he is acknowledged beyond the context of Black art. Williams’s complex relationship with Britain—never identifying as British, but as a colonial subject, while employing the language of an English gentleman—is here presented in his own words: from his first visit to Britain in 1952, to his first glimpse of snow (“white sand”), and impressions of Plymouth and Leicester, the latter a city “accustomed to coloured students” and that “frequently meets with foreigners”.

The groundbreaking work came first beyond the capital, with exhibitions in York and Liverpool. Interest in London came late and often with identity tags, save for his work with the Grabowski Gallery and New Vision Centre Gallery. Here listed in a chronology, if not all indexed, these exhibitions offer routes for research into regional and transnational art networks.

Present in prominent collections

An interest in, and familiarity with Williams persists across central, eastern, and southeastern Europe. His presence in prominent contemporary art collections demands further research beyond this book. The Earth Will Open its Mouth, a 2022 exhibition at Muzeum Sztuki in Lodz, Poland, placed Williams and Erna Rosenstein together “in conversation”, as painters communicating the traumas of colonial violence and genocide: historical and contemporary.

The particular interest of Ian Dudley, one of the book’s co-editors, in volcanoes, reflecting rising public awareness in the Martinican thinker Édouard Glissant, should not be considered mutually exclusive with tremors on the European continent. Williams contributed to what became the Skopje Solidarity Collection in Macedonia, following the earthquake in the former Yugoslavia in 1963, a work absent from this text. Warm embraces with Maxim Shostakovich, son of the Russian composer, captured here in photographs, speak to their personal friendship as well as shared “apocalyptic” artistic forms. Did Williams’s interests extend to the Communist politics of Soviet Russia?

This only serves to underscore how vital such books are: the basic “taking care” of histories allows for speculative inquiry. In her essay touching on an archive photograph from 1982-83 of Aubrey Williams dressed as a sensei (martial arts teacher), Maridowa Williams, the artist’s child and co-editor of this volume, remarks that he rarely missed a martial arts screening at cinemas near their home in north-west London. Was Bruce Lee, a figure heroised by many artists of migrant and diasporic backgrounds, ever on the bill?

Finally, the wealth of reproductions in Art, Histories, Futures, many dated 2024, show how publications can be a powerful instrument for encouraging institutions to catalogue and care for their works: research as activism. Futures—plural—is a fitting end for the title of this book: the start, rather than the final word on Williams’s practice.

• Ian Dudley and Maridowa Williams (eds), Aubrey Williams: Art, Histories, Futures, Paul Mellon Centre, 384pp, 200 colour, & b/w illustrations, £40 (hb), published 22 October 2024

• Jelena Sofronijevic is a curator, writer and producer of the EMPIRE LINES podcast