Making Her Mark: A History of Women Artists in Europe, 1400-1800 is an ambitious and handsome publication, which accompanies the exhibition co-organised by the Baltimore Museum of Art and the Art Gallery of Ontario; it opens at the latter on 27 March (until 1 July 2024). The book’s importance lies in being a scholarly assessment of the “state of the discipline”—as introduced in the editors’ preface and then explored within nine themed chapter essays—as well as a full visual record, with catalogue entries, of the exhibition’s contents.

The preface offers a pithy survey of how European women artists and makers of the early modern period have been judged. In sum it is a miserable, centuries-long tale of predominantly male art historians, curators and commentators/critics dismissing women as substandard to their male contemporaries and counterparts, or wilfully ignoring their very existence in tandem with whole areas of visual art production dominated by women practitioners. Things improve after the ground-breaking work of feminist art historians from the 1970s onwards, although, as argued here, the present environment of “rediscovery”, fuelled in part by commercial imperatives, remains framed by the limited parameters of a “canon” established by men, about men. As the editors observe: “Organizing an exhibition devoted to women makers during this moment has been exciting and gratifying…but also makes clear how our collective perspective continues to be shaped by biases toward narratives of exceptional and solitary genius.”

The core stated aim is to move towards a more diverse, inclusive and therefore accurate appraisal “of women’s creative accomplishments”. And it succeeds

Ann Sutherland Harris and Linda Nochlin’s exhibition, Women Artists, 1550-1950 (Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1976), with its broad geographic and chronological sweep, is here celebrated as “foundational”, even as it is critiqued for perpetuating this limited idea of what makes a maker: “its approach to understanding women’s contributions to, and status within, the artistic culture of early modern Europe still subscribed largely to the male-established criterion of singular brilliance with a paintbrush.” No doubt Harris and Nochlin would argue that revolutions need to start somewhere. Even so, Making Her Mark follows more closely the example of Rozsika Parker and Griselda Pollock’s Old Mistresses: Women, Art and Ideology (1981), which sought to subvert rather than augment the canon. Mindful of what Pollock calls “ghettoisation”, the editors “do not deny male artists’ involvement or attempt to present a fantastical world in which women makers operated independently from their circumstances”, notably significant societal shifts over the four centuries covered. The core stated aim is to challenge the “painting-centric” narrative, moving towards a more diverse, inclusive and therefore accurate appraisal “of women’s creative accomplishments”. And it succeeds.

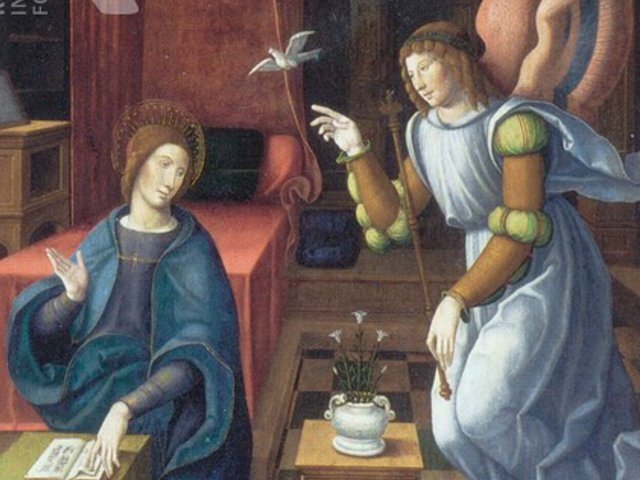

In the first essay “Not Seen, Not Heard”, Andaleeb Badiee Banta, with a hint of the righteous anger of the Old Mistresses, continues the preface’s call to seek out the marginalised “unexceptional woman artist”. Painters and sculptors like Anguissola, Gentileschi, Roldán and Vigée Le Brun were the exception not the rule. How they negotiated the world of elite patronage and, often, great public fame is the subject of Paris Spies-Gans’s chapter. Other essays focus on particular materials (textiles, drawings, prints) or practice, notably the collaborative environment of the workshop, or overarching subjects such as “science”, which embraced a variety of makers and media, from botanical watercolours to wax anatomy models. The final essay broadens the discussion to “European Makers in a Global Context”. The remainder takes the form of a catalogue of the “Works Exhibited”, with an index of the makers whose works are illustrated throughout the publication.

The vision of a woman in a pink silk robe unveiling a human head with its brain fully exposed, feels, even now, like an act of defiance

There is, of course, a fair amount of “fine art” – it is where the scholarly and curatorial focus, heretofore, has been concentrated – but presented in parity to embroidery by unidentified nuns and Meissen porcelain “probably” or “possibly” decorated by a known artist working for the factory, Anna Elizabeth Auffenwerth Wald. Within this dazzling wealth and variety of creative output, Anna Morandi Manzolini’s wax models of eyes (in and out of the socket) and her mesmerising Self-portrait Dissecting the Brain (1750-1760) stand out: the vision of a woman in a pink silk robe unveiling a human head with its brain fully exposed, feels, even now, like an act of defiance.

The authors are clear that Making Her Mark cannot be definitive, with issues around social class, for example, yet to be fully considered. But their call to action is manifest.

• Making Her Mark: A History of Women Artists in Europe, 1400-1800, by Andaleeb Badiee Banta, Alexa Greist and Theresa Kutasz Christensen eds, with Babette Bohn, Madeleine C. Vilijoen, Yassana Criozat-Glazer, Brittany Luberda, Virginia Treanor and Paris A. Spies-Gans. Goose Lane Editions, 264pp, 300 colour illustrations, $60 (hb), published 17 October 2023