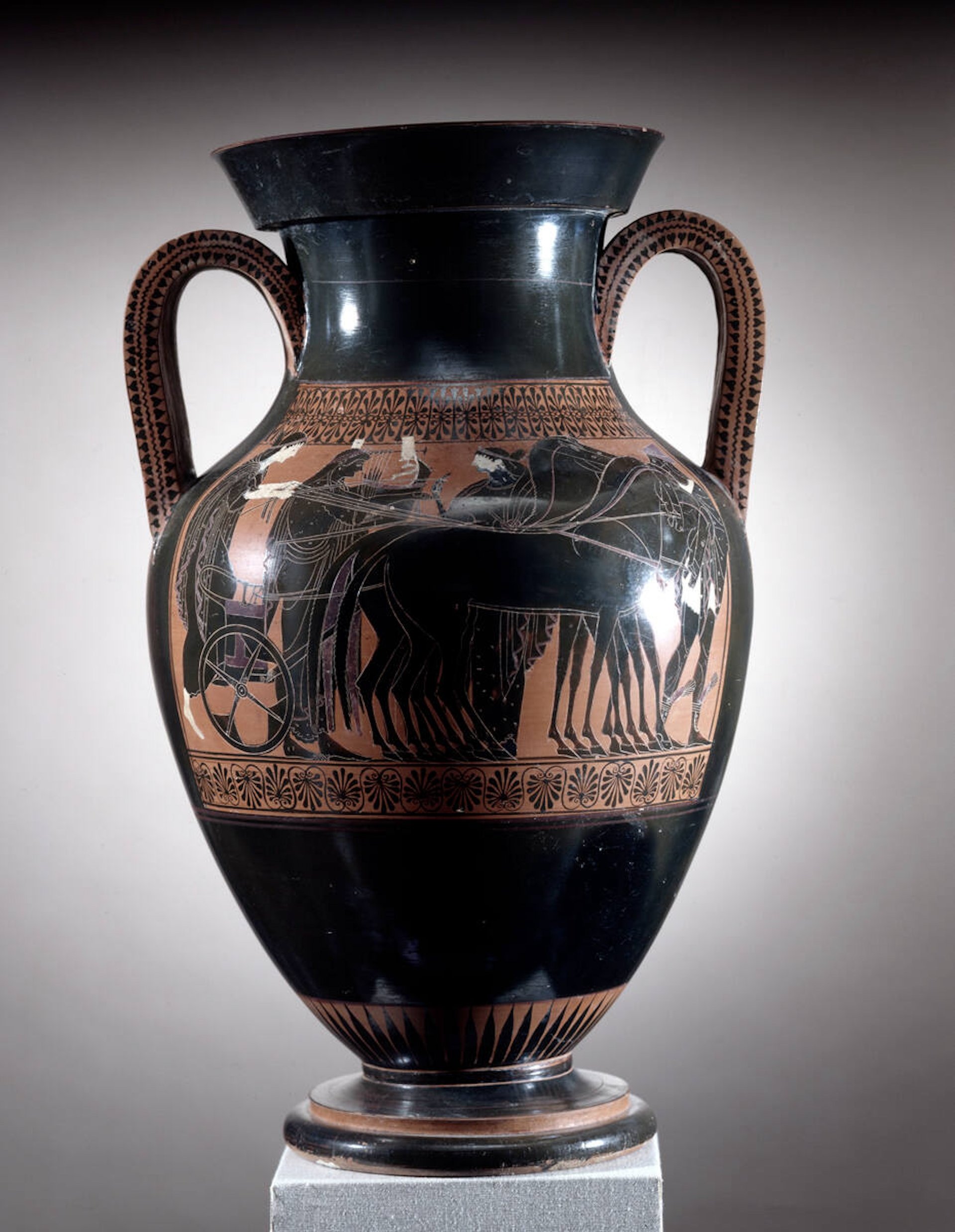

The Worcester Art Museum (WAM) in Massachusetts concluded an agreement this week with the Italian culture ministry to return two antiquities from its permanent collection—a black-figure amphora that dates from between 515 BCE and 500 BCE and a black-figure kylix (or drinking cup) that has been dated to 500 BCE—that had been illegally taken out of Italy.

The first-of-its-kind agreement for the museum permits the 127-year-old institution to keep the objects, where they currently are on display, along with new labelling that identifies the pieces as having been looted, as a long-term loan of four to eight years. At the end of this loan period, these objects will be returned to Italy in exchange for a loan of comparable antiquities from Italian museums, and these loans will recur on a rotating basis.

This agreement also reflects the first fruits of the museum’s decision to hire a provenance research specialist, Daniel W. Healey, last year. A growing number of museums around the US have brought on curatorial staff members whose primary jobs are to search the institutions’ collections for objects that have missing or no provenance, which suggest that they may have been stolen or looted. These two ancient Greek objects were Healey’s first finds.

Claire Whitner, the museum’s director of curatorial affairs, says that she and others at the museum had become increasingly aware “that we did not have the in-house expertise to know which objects might have provenance issues or, if they were identified, how best to handle them. While our curators examine and vet provenance when they acquire new art, so many objects came into the museum in the 20th century when the standards at museums were different.” She adds that it is unknown how many objects in the museum’s holdings have missing provenance, but “that is what we are working to determine”.

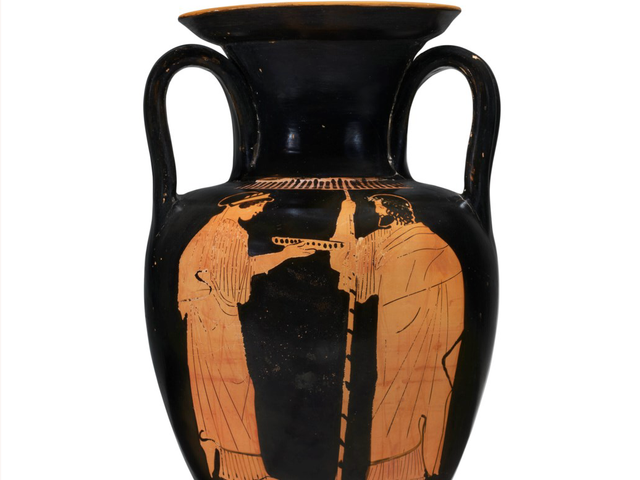

Black-figure amphora (storage jar), attributed to the Rycroft Painter, around 515-500 BCE Courtesy Worcester Museum of Art

Healey’s discovery of the two ceramic objects came about after he made a search of the collection’s database, looking specifically for the name Robert Hecht. “When we searched for ‘Robert Hecht’, the amphora came up,” he says. “That initiated an investigation into this object and Hecht’s role in its provenance.”

Hecht, who died in 2012 at the age of 92, was a notorious figure in the antiquities world, acting as a dealer of Greek and Roman objects. Although never convicted of looting or smuggling, Hecht worked with known antiquities smugglers and often was investigated for his part in the trafficking of ancient objects, most notably a 2,500-year-old Euphronios krater (a two-handled vase) that was sold to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1971 for $1m and ultimately returned to Italy in 2008. The Italian government claimed that the krater had been looted from an excavation site near Rome, and an arrest warrant was issued for Hecht by an Italian judge, although the warrant was later revoked.

The amphora—which is attributed to the Rycroft Painter, an Athenian vase-painter who was active in the last decades of the 6th century BCE—was purchased by the Worcester Art Museum in 1956 from a Swiss art collector and dealer, Elie Borowski (the price paid was not revealed by the institution). At the same time as the purchase, Borowski made a donation of the kylix.

“Going through the object file for the amphora, however, it became clear that Borowski had acquired it from Hecht,” Healey says. “The fact that Hecht was the first known possessor of the amphora is a red flag, given what we now know about Hecht’s activities in Italy at this time.” The information about the amphora mentioned the kylix, which Borowski had also acquired from Hecht. “One object thus became two, and after additional archival research it became clear that the amphora and kylix shared a provenance, from Hecht to Borowski to Worcester.”

Soon after, the museum contacted Italian authorities, providing photographs and information about the vases to the Carabinieri (the Italian national police force), Healey says, “and they pretty quickly got back to us with confirmation that the vases were in their database of stolen cultural property. They made a formal request for the return of the vases and at the same time offered to enter into a cooperation agreement with the Museum.” The negotiations went smoothly, with an agreement signed on Tuesday (28 January).