UPDATE: On the evening of 24 March, several hours after this article was published, one of the artefacts under examination, lot 76, the Nolan amphora, had been withdrawn from the sale. It is no longer listed as one of the objects on offer in the auction. By the morning of 25 March, the other artefact, lot 90, the Roman cavalry helmet, had also been withdrawn, as indicated by a sale room notice on its listing.

An ancient Greek vase and a Roman cavalry helmet due to hit the auction block during Christie’s forthcoming antiquities sale in New York on 12 April may have questionable provenances that include being previously sold by dealers who are known to have trafficked in illicit artefacts, a detail that is absent from the sale catalogue, according to the forensic archaeologist Christos Tsirogiannis, an associate professor and research fellow at the Institute of Advanced Studies, University of Aarhus in Denmark.

Tsirogiannis says the vase, a Nolan amphora that dates to around 450BC, can be traced to convicted antiquities dealer Gianfranco Becchina through his photographic archives, which were seized by Swiss authorities in 2001 and turned over to one of Italy’s main law enforcement agencies, the Carabinieri. The helmet, he says, can be traced also through photographic archives to Robert Hecht, who in 1972 sold the Euphronios krater to New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, an artefact which was later found to have been looted from Italy and that was repatriated to the country in 2008. Hecht stood trial in 2005 for allegedly dealing in looted artefacts, but was never convicted. Despite that he was for years under suspicion of channeling looted artefacts to museums with a cadre of coconspirators, including the convicted Italian antiquities dealer Giacomo Medici.

According to Tsirogiannis, who has access to these photographic archives through what he describes as “various authorities”, it is unfortunately common for auction houses to offer artefacts without checking the archives to confirm whether an object was possibly obtained through illicit means. However, access to the archives, which are not publicly available, has proven difficult or impossible for some, while others are given free rein to search for looted objects among the-dust covered antiquities portrayed in the photographs.

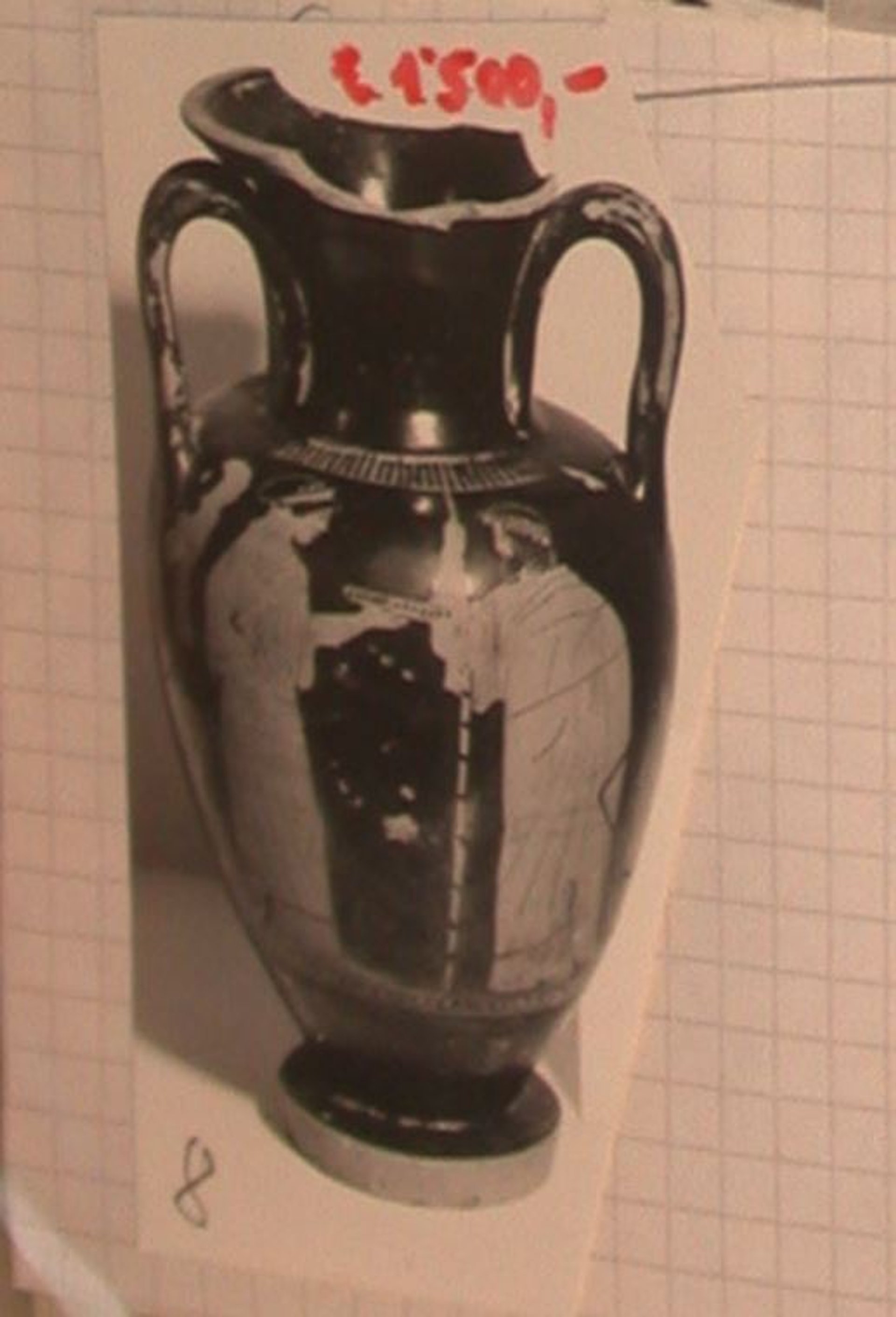

The same vase being auctioned by Christie's, from the the Becchina archive, with most of the rim and part of the neck broken, parts of the paint missing, a restoration which Tsirogiannis says is missing from the provenance.

Tsirogiannis claims that anyone, whether a collector, researcher or an institutional representative, can reach out to the Carabinieri and inquire about the nature of an object. In a 2015 statement, Christie’s said, “We have in the past sent individual queries to the Carabinieri but they have not responded. We are, of course, continuing actively to try to explore this route both with the Greek and Italian authorities as well as through other avenues… We are asking for access and full transparency for us but also for the art market as a whole.”

“Anyone who has even one object can ask the Carabinieri to check that object by sending an image,” Tsirogiannis says. “And they ought to, though not many do. Even private collectors fail to check the collections they put together. This is something that should change, it’s a matter of their own safety. The members of the market, dealers, auction houses and collectors, are putting themselves at danger. By they are turning a blind eye they risk losing money, losing the objects they care about and jeopardising their reputations.”

In regards to the two lots that aroused suspicion, a Christie's representative said, "Under no circumstances would Christie’s knowingly offer a work of art where there are valid concerns over provenance or authenticity. We devote considerable resources to investigating the provenance of the works we offer for sale. In the case of the upcoming sale of these lots, the research we conducted gave us no reason to believe that any of these lots are from an illicit source or that the sale would be contrary to applicable law. We continue to conduct research on these items."