“You cannot do business on a dead planet,” the photographer and climate activist Cristina Mittermeier says when asked what she’d say if she got five minutes with one of the world’s leading chief executives.

She may well get that chance. Mittermeier is one of a select number of artists invited to be cultural leaders at the World Economic Forum’s annual meeting in Davos, Switzerland, alongside more than 2,000 business leaders, heads of state and leaders of civic society.

The Mexico-born photographer is presenting a large-scale exhibition commissioned by the World Economic Forum and based on her latest book, Hope, which captures the fragile beauty of Earth’s biodiversity and attempts to convey the wisdom and fighting spirit of Indigenous peoples trying to save it. She will give a talk and participate in panel sessions. “But, more importantly, I get to socialise and spend time with people that I would never have access to otherwise,” she says. “I want to tell them that we cannot keep kicking the can down the road. It’s now or never.”

Ocean conservation

Mittermeier speaks to The Art Newspaper in late December 2024 on a video call from her sail-boat, SeaLegacy 1, then anchored in Raja Ampat, an archipelago in the heart of the Coral Triangle in the Southwest Pacific Ocean. “We’re here to tell the stories of everything that’s wrong, but also all the amazing people that are working to try to protect it.”

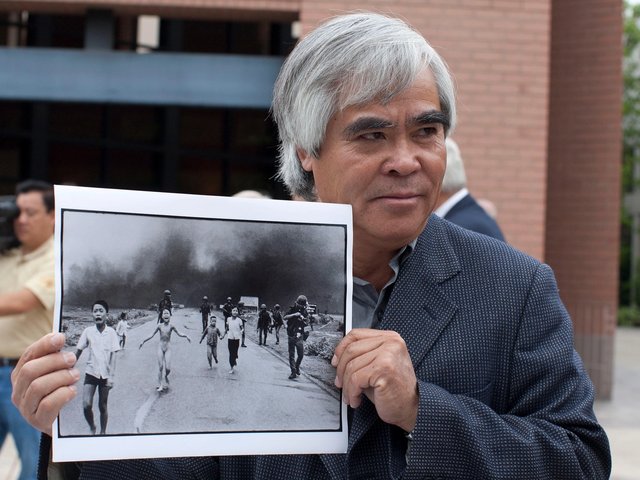

Mittermeier on her sail-boat SeaLegacy 1

Cristina Mittermeier Photography LLC

Such sentiments are typical of “Mitty”, who remains positive and upbeat, despite her daily confrontation with the beginning of the end of the world. She spends around six months of the year aboard the 62ft catamaran, living and working alongside her Canadian partner Paul Nicklen, the acclaimed wildlife photographer and film-maker with whom she founded SeaLegacy, a non-profit advocating for ocean conservation. “We live together. We work together. We’re both storytellers. Just this afternoon, we were diving with manta rays here in Raja, and we were kind of fighting for the best position, elbowing each other,” she says, laughing, before expertly returning the conversation to the most important matter in hand.

“The ocean is the largest and the most defining ecosystem on planet Earth. Yet it’s so unknown. It’s so mysterious. It’s vast. It’s unexplored. And it’s a dangerous place to work. So, the first order of business is to survive,” she says of her work in often the most remote of places.

Mittermeier's Alley of Giants (2009) shows the “Alley of the Baobabs” in Madagascar

Cristina Mittermeier

She and Nicklen started out as scientists, having both studied marine biology before becoming photographers. She went on to found the International League of Conservation Photographers, while he became an icon of visual journalism, reporting stories from the polar world for National Geographic. The problem with the science, Mittermeier found, is that “nobody’s listening. It’s a very difficult language to interpret and then to find an emotional connection to. I realised that most people don’t speak science, but we all speak photography, and we are all curious about the natural world.”

The SeaLegacy message

In the early 1990s, working at Conservation International and, looking at organisations like the World Wildlife Fund, she realised that their budgets for communications were small. And the people telling the story of our planet was very narrow — people like the BBC, National Geographic and a handful of organisations, mostly viewed through the lens of an “elitist luxury entertainment” experience.

“So, with SeaLegacy, we wanted to use our skills as photographers, as communicators. We also have a very large social media following [she has 1.6m Instagram followers, while Nicklen has 7.2m, making him perhaps the most popular photographer on the platform]. They are people who love photography, who love diving, and they trust us. They’re interested in whatever frontline news we bring. And so we use that. It’s amazing to be able to have a conversation with so many people around the world.”

Mittermeier has a powerful, and honest message for the leaders at Davos. She will share her firsthand harsh reality of the world’s current state, emphasising that while it may be tempting to stay detached and oblivious to the struggles of the planet, the truth is that the situation is worsening, and we are all feeling its consequence.

But she’s very much aware that people recoil from too much bad news, so her photographs focus on hope, not horror. “It’s reminding us that the planet is still beautiful. There are pockets of just incredible biodiversity that are worth protecting.”

That’s the role of the artist, she declares. “Art exists to make the revolution irresistible, and my job as an artist is to build a life raft that we all can hold on to while we become activists, while we demand from our legislators a planet for our children to live in.” However, she’s determined not to sugar-coat the seriousness of the climate emergency.