“At some point, you're no longer the little punk with the camera,” says the Dutch photographer Anton Corbijn. “People know your work, and they want your input.”

Corbijn is reflecting on a lifetime photographing famous faces, and the challenge, fundamental to all portraiture, of capturing something beyond the facade that is presented to camera.

“Sometimes I photograph the person. Sometimes I photograph the idea of the person,” he once said in a past interview. Now, speaking on Zoom from Kenya, he expands on the idea. “What I find interesting about shooting people in the public eye is you already know a lot about them," he says. "And people generally know a lot about the person [in the photograph]. So you play with that knowledge. You can either show them a very different way, or go deeper in that direction.”

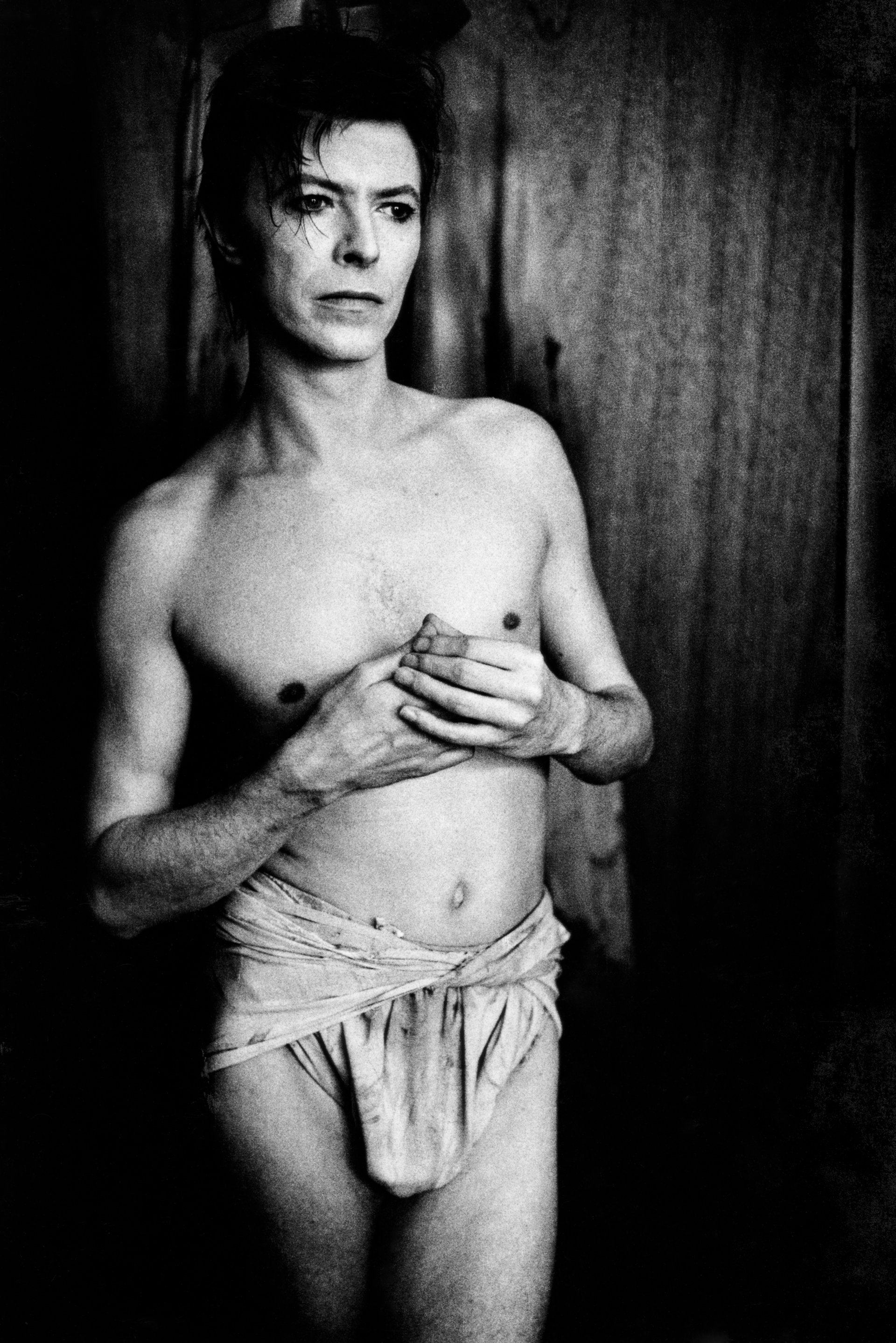

David Bowie, Chicago, 1980 © Anton Corbijn

He is talking ahead of his collaboration with Simon de Pury, the latest in the art dealer’s series working with artists in their own studios. Opening today, de PURY Presents: Anton Corbijn covers four decades, starting in the 1980s, when he established himself as one of the most distinctive photographers of his generation.

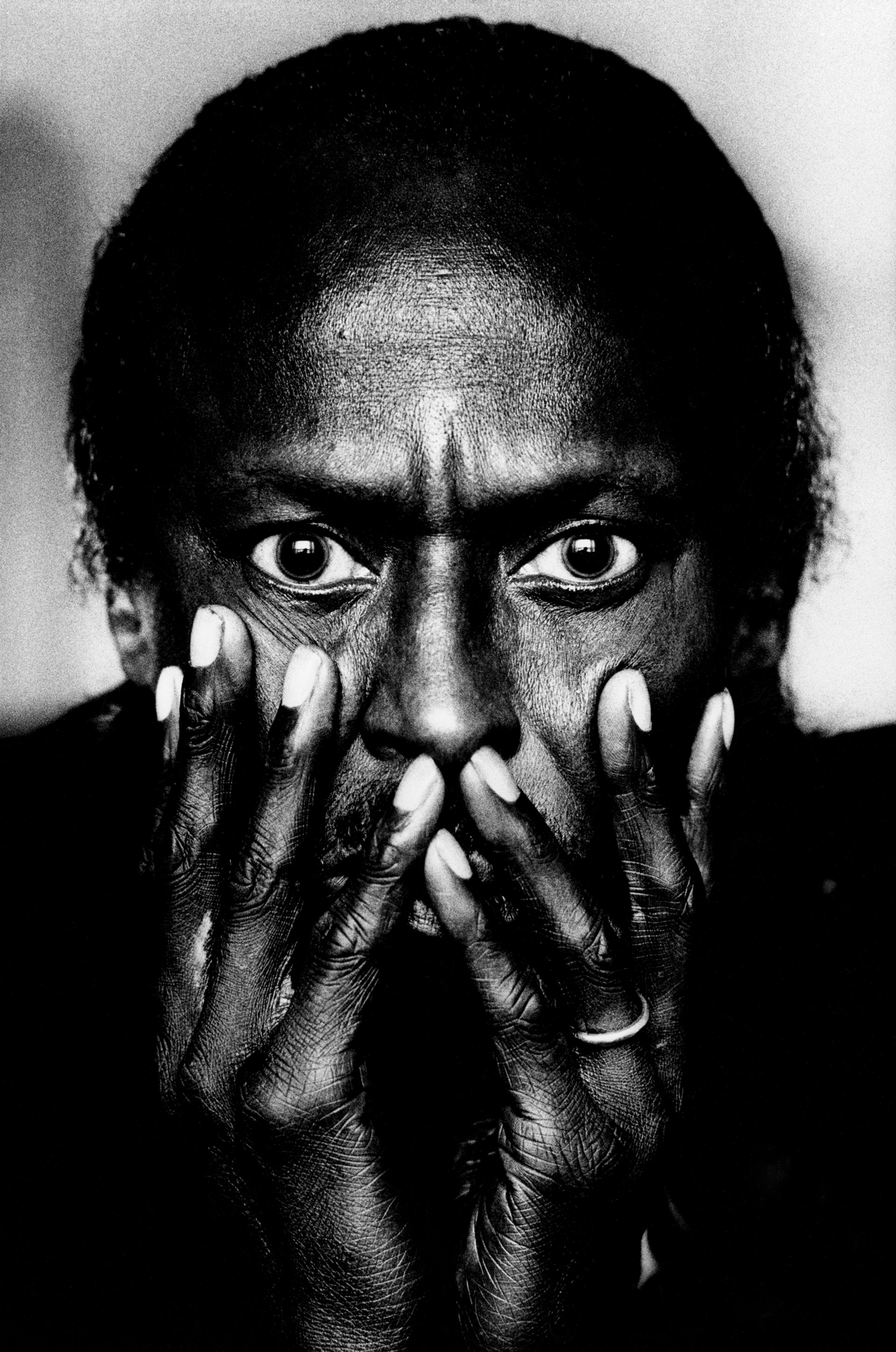

Exhibited out of the photographer’s studio in The Hague, and at de-Pury.com, the show includes some of Corbijn’s most notable portraits: Miles Davis in close up, with Corbijn’s silhouette visible in the reflection of the jazz artist’s pupils, and of the late fashion designer Virgil Abloh, who died of cancer in November, aged 41.

Miles Davis, Montreal, 1985 © Anton Corbijn

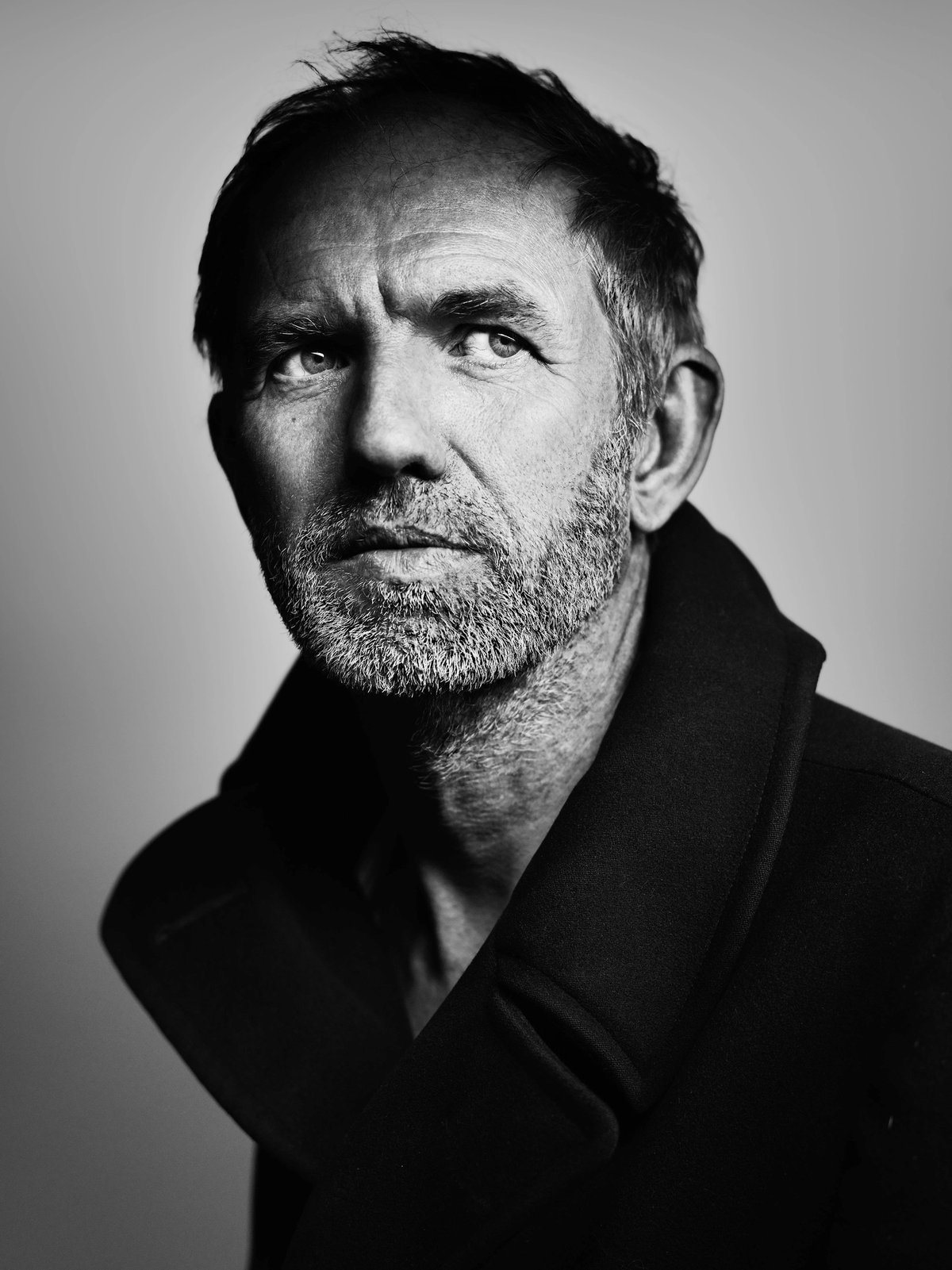

On view close by is an unguarded picture of David Bowie, shot while playing the lead in a US theatrical tour of The Elephant Man, and a kingly image of Dave Gahan of Depeche Mode, the avant-pop band that credits Corbijn as its unofficial fourth member.

The show also highlights Corbijn’s work in fashion, models such as Naomi Campbell and Kate Moss presented together with designers including Rick Owens and Vigil Abloh, alongside his many portraits of artists over the years, from Lucian Freud to Damien Hirst.

Damien Hirst, Stroud, 2011 © Anton Corbijn

This world of luminaries that Corbijn now inhabits is a far stretch from his humble beginnings in Strijen, a small town on a small island in South Holland where his father was the local preacher.

Music called to him young; the beckoning of “a promised land somewhere” beyond the estuary. And later, when his family moved to the mainland, the shy teenager used his father’s camera as a crutch to hide behind; a reason to get up close to the bands that would provide his eventual escape.

In his mid-20s, the self-taught photographer moved to London at the height of the post-punk movement, and it was here, in the early 1980s, that he found his place.

Shooting prolifically for the NME, he brought a newfound gravitas to music photography. He became known for mood-saturated images full of artistry and light and shadow. His painterly technique with a camera came with with a laser-focused determination to push himself—and, in turn, his subjects—to new heights.

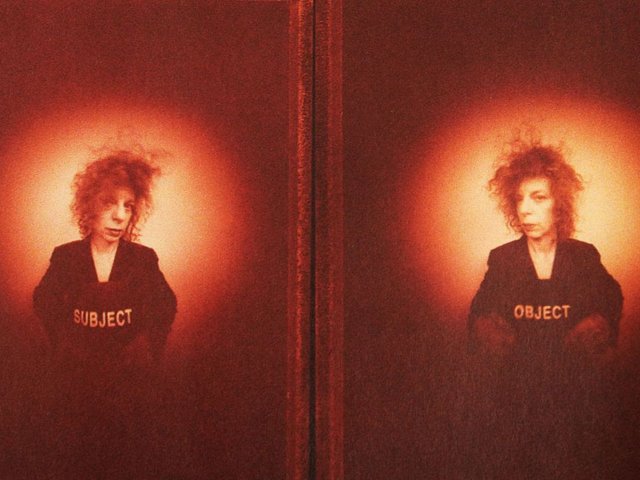

Naomi Campbell, London, 1994 © Anton Corbijn

His work soon transcended the genre he had come to redefine, and whose label he was determined to evade. “I'm sure it's slippery ground, but I just don't like the term 'rock photographer', because, to me, that paints a picture of somebody who's always backstage and lives that life. And I'm not. I'm somebody who documents the people who play the music. So I was keen from the start not to photograph them with instruments. I wanted to show them as the people who went through the pain to create a song."

As Corbijn has aged and gained experience, he finds painting is now the medium that often compels him the most.

"With painters, it's the opposite," he says. "I think, deep down, I wanted to be a painter more than a musician. I am always really curious to see what painters do in the studio, and I love the idea that they start with nothing. I identify with the pain of creation more than anything else.”

By the turn of the decade, Corbijn was living in Los Angeles and photographing actors and directors alongside musicians. He shot more than two dozen music videos and eventually came knocking on Hollywood’s door as a movie director. His first movie was the critically acclaimed Control, in 2007, a biopic of Joy Division frontman Ian Curtis, who he had photographed in London some 28 years earlier, months before his suicide.

Rick Owens, Paris, 2018 © Anton Corbijn

He followed with The American, starring George Clooney, in 2010. Then came A Most Wanted Man, destined to be one of Philip Seymour Hoffman's final films, and Life, a tribute to fellow photographer Dennis Stock.

Each film was shot in quick succession, in 2014 and then 2015. Corbijn was due to shoot a fifth film, but that fell through, and he found himself gravitating back to stills.

"I do love the simplicity of photography," he says. "It's just you and a camera. And there's something incredibly beautiful about that. And powerful.” After the stress of making movies, "and the amount of people that you have to deal with to get an image", photography offers so much freedom. "I love it even more now," he says.

"Actors are much more insecure than musicians," he says. "It's hard for them to pose when they're not in a role. Whereas musicians are very much who they are: they create their own thing, they write their songs, they decide how they dress. Actors generally like to look beautiful. And, for me, it was always the search for beauty inside, not the outside, because I was uncomfortable with that.”

He’s not done with filmmaking yet: “I miss the adventure,” he says. Corbijn is currently completing a documentary on Hipgnosis, the design studio who created many of rock music’s most famous album covers, including Dark Side of the Moon and Wish You Were Here for Pink Floyd. And he is “playing with one or two stories for them for a movie” he says.

“I definitely want to have made five movies.” Why five? “Because if I say I'm happy with four, then I'm never going to make the next one. So after five, maybe then I'll say I have to make 10! Filmmakers go on forever. Like painters.”

• De PURY Presents: Anton Corbijn is available to view on www.de-pury.com and on display at Anton Corbijn’s studio located in The Hague, Amsterdam by appointment only. Until 28 February