In this column and beyond I have written about many environmentally-aware artists, but Anya Gallaccio is exceptional. Right from the early 1990s with her dramatic durational works involving masses of oranges, roses and gerbera flowers, as well as—in one memorable case—a 35-ton block of ice, she has distinguished herself as having a more organic and elegiac approach than most of her YBA Contemporaries. For Gallaccio, process matters as much as product, and the fact that so much of what she has made has left little or no evidence of its existence marked out her practice as a rare example of sustainability at a time when the eco-movement was not so widespread, especially among younger artists.

Anya Gallaccio is a pioneer of sustainable contemporary art practice

Photo: Benjamin Eagle

More than three decades later Gallaccio is still harnessing the forces of nature, using a wide range of natural substances that rot, melt and putrefy but also grow and transform over time. While much of her work continues to sit lightly on the planet, it also goes beyond green matters to encompass a rich range of conceptual, political and art historical concerns. These range from female stereotypes and the “male” rigidity of minimalism to ideas around death, permanence and mortality, her materials acting like a very particular type of memento mori, a physical reminder of how all organisms—including homo sapiens—both live and die in today’s world.

Change and decay, in their broadest terms, are addressed in Preserve, Gallaccio’s current exhibition at Turner Contemporary in Margate, which marks the most comprehensive showing of her work to date. The densely packed gerberas sandwiched between seven wall-mounted rectangular panels of glass in the work Preserve Beauty (1991-2024), from which the show takes its name, were a lush velvety red at the September opening—but now they are blackened, oozing and shrivelled, and furred with grey fungus in places. Some have fallen from their glass casing and lie scattered like corpses on the floor below. It is a shocking transformation. Rarely are we given the chance to scrutinise entropy at such close quarters and by doing so it becomes evident that there is a beauty and complexity in these putrid tableaux of decomposition, both in their variety of textures and monochrome hues and their relentless disruption of a once orderly presentation.

Installation view of Anya Gallaccio, Preserve ‘Beauty’ (1991/2024), featuring 1,700 gerbera held between seven panes of glass and a gallery wall

© Anya Gallaccio. Courtesy the artist and Turner Contemporary. Photo: Jo Underhill

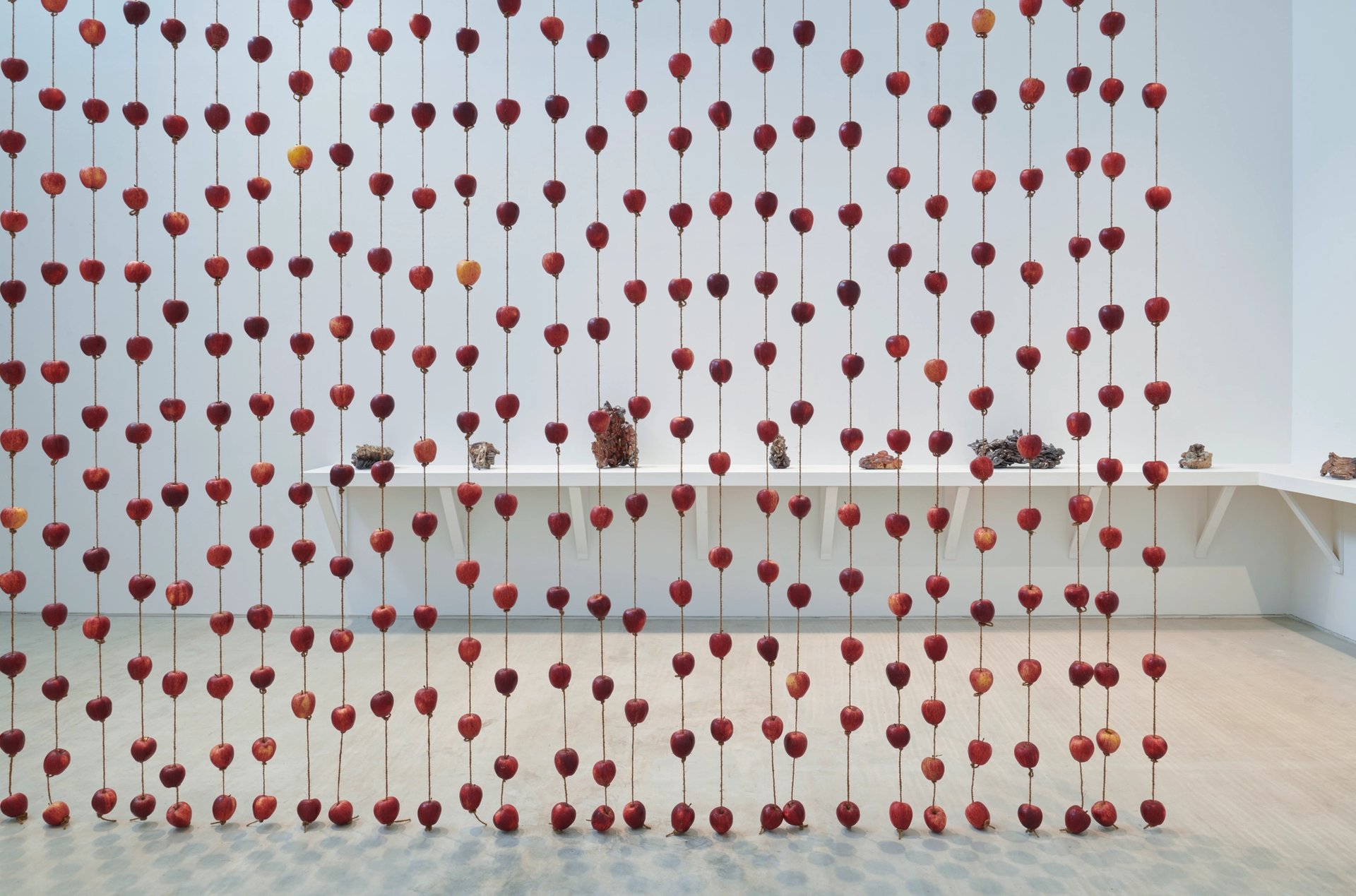

Sometimes you can smell the work before you see it. Falling From Grace (2000) consists of a multitude of Gala apples threaded on vertical strands of hop twine to form a giant floor-to-ceiling curtain. As they shrivel and slide towards the floor, these once plump mass-produced supermarket fruits give off a powerful cidery aroma that fills their own gallery and permeates the whole space. Spectacular and poignant, they live up to their title, evoking a post-lapsarian Garden of Eden turned boozy and rancid but also compelling and seductive. It’s especially fascinating to see how each of what were once almost identical apples are now decaying in their own very particular ways: some are wizened and dry, others explode with mould. Way past their shelf life, misshapen and falling from commercial grace, they are have become dynamic, unpredictable and individual.

Given her emphasis on the ephemeral, Preserve might seem an unlikely title for Gallaccio’s Turner Contemporary show. But like everything she does, the name is rich in various and sometimes conflicting meanings and connotations. The glass covering the eponymous gerbera piece protects the blooms while at the same time also accelerating their destruction. Then there’s the domestic association, with jam and all “preserves” commonly contained in glass jars—and traditionally made by women—homely female associations that Gallaccio deliberately subverts with her minimalist language of grids and geometric presentation.

Installaton view of Anya Gallaccio, Falling from grace (2000), featuring 2,700 “gala“ apples threaded on hop twine

© Anya Gallaccio. Courtesy the artist and Turner Contemporary. Photo: Jo Underhill

“With “preserve” I was also thinking environmentally in terms of taking care of what’s around us and being aware of things,” she told me, while emphasising that this aspect of preservation was not an exercise in nostalgia but in maintenance and looking to the future.

For as both the natural world and Gallaccio’s exhibition repeatedly confirms, out of decay new life emerges. In addition to the very active strains of bacteria and fungus flourishing in her mouldering blooms and apples, life is also unexpectedly bursting forth in another work, The Inner Space Within (2008-24) which centres around the crown of a mature ash tree which had to be felled due to ash dieback disease. From the crown, what initially seemed to be inert woody surfaces now bloom with a covering of vivid green moss, while out of one of its crevices sprouts a jaunty youthful “cuckoo tree” of native elder, which appears to be flourishing courtesy of its felled host. This arboreal corpse should teem with even more life when, after the exhibition, it is returned to its original home on the Lees Court estate near Faversham in Kent, where it will be left to create new habitats for local wildlife.

A living legacy

In keeping with its ethos of sustainability and future regeneration, Preserve will live on after the exhibition closes on 26 January in broader ways too. All its organic matter will be composted to support more growth in Turner Margate’s garden while anything non-organic is to be meticulously recycled and re-used in myriad ways. The fact that Kent is known for its apple growing was central to Gallaccio’s planning of the show, and a crucial offsite element is an orchard of 58 heritage apples also being planted on the Lees estate. They include the Decio, the oldest cultivated apple on record brought to the UK by the Romans and a rare local red fleshed strain called Sops in Wine. The Margate orchard will be surrounded by a hedge of wild crab apples grown from gala pips that Gallaccio harvested from the Falling From Grace apple curtain. (Apples of all strains, if planted from seed, will always revert back into their wild state).

Installation view of Anya Gallaccio, Time is our choice of how to love and why (ebony) (2005)

© Anya Gallaccio. Courtesy the artist and Turner Contemporary. Photo: Jo Underhill

Not only will this hedged orchard of wild and ancient cultivated apples remain as a living work of art and a living legacy of an extraordinary show, it will also be used to nurture knowledge by forming an outdoor classroom for local children. “I see the orchard as a sculpture but it will also remain as a living resource for schools.” Gallaccio says. “We’re working with teachers on a pilot cross-curricular project called An Apple a Day where you can teach maths, science, history, geography, literacy—all subjects—through the apple.”

At the beginning of what will undoubtedly be another year of acute environmental challenges, in a corner of Kent the seeds of hope are being planted. Here’s to the power of art and of the apple!

- Anya Gallaccio: preserve, Turner Contemporary, Margate, 28 September-26 January 2025

- You can read The Art Newspaper’s recent interview with Gallaccio here