The fire that tore through the roof of Notre-Dame devastated the cathedral, leading many to fear for the World Heritage Site’s future. But despite the tremendous loss, the fire has given experts an exceptionally rare opportunity to investigate parts of the cathedral’s structure that were previously unreachable, revealing forgotten burials and providing insights into the working methods of medieval artisans.

“The worksite enabled us to collect an enormous and unprecedented amount of data on the materials used in the construction of the cathedral's masonry, and on the way in which these materials were worked and put up together,” says Yves Gallet, a professor of the history of medieval art at Bordeaux-Montaigne University, who leads the working group studying the cathedral’s masonry. “In order to do this, we had to be able to examine the walls, pillars and vaults very closely—which we were able to do from the scaffolding, with unrivalled precision in observing and recording the data, and with the possibility of taking samples from places that had not previously been accessible.”

Piles of debris sorted for study or for reuse

Once firefighters had quelled the blaze, experts began the complex work of securing the building and sorting the piles of damaged materials, both for study—to guide future restoration—and in the hope that some could be reused. These specialists were divided into nine working groups—among them, metal, stone and glass—and the archaeologists excavated spaces where scaffolding and cranes would be installed, and conducted geophysical surveys. As melted lead had contaminated the air and materials, the researchers had to conduct their collection and analysis with extreme care. Experts drove remote-controlled robots—one with a bucket, one with a claw—to pick up materials and move them to safe zones, wore protective clothing and masks, and even used decontamination showers on site.

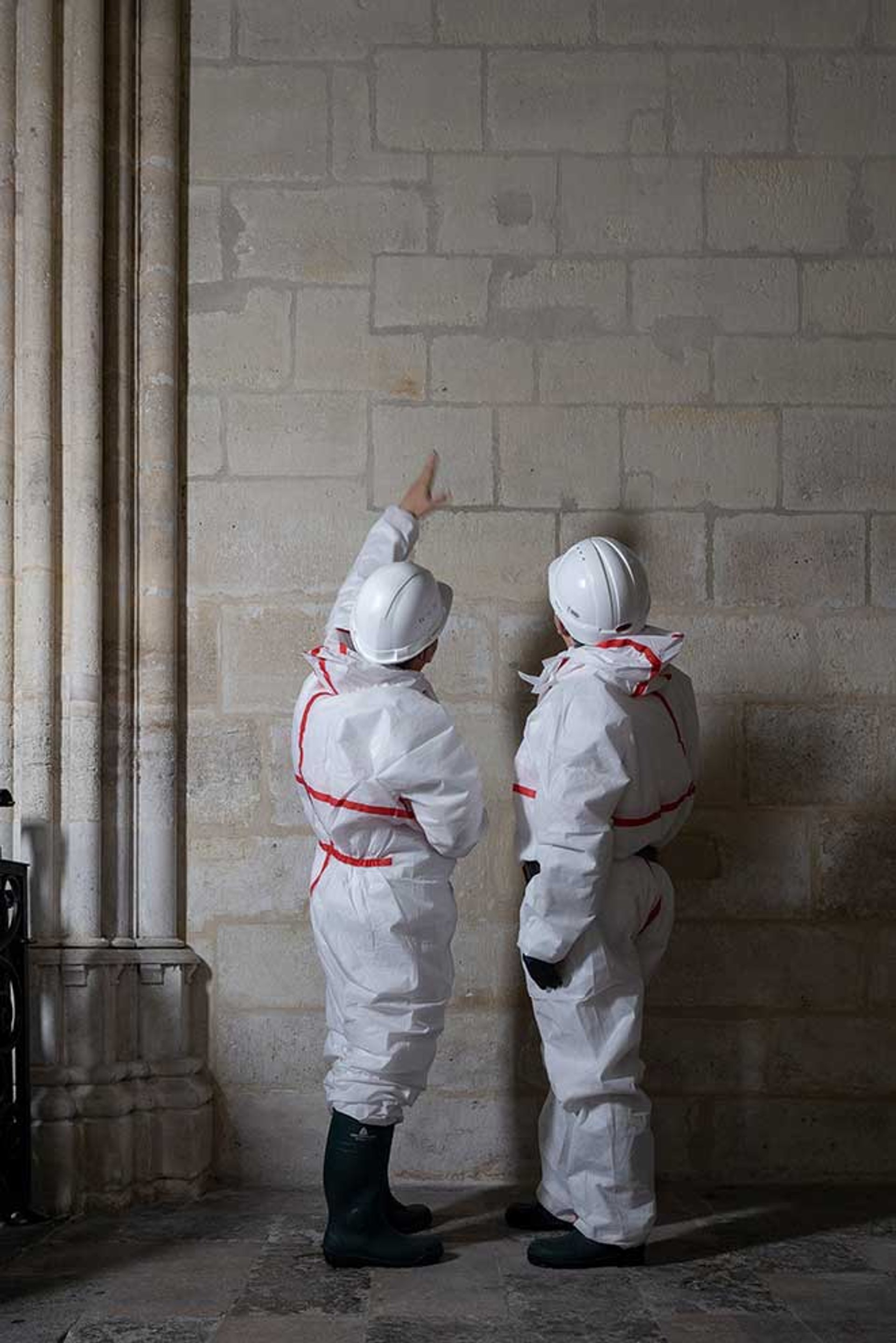

Members of the stone working group examine a wall in the 12th-century Gothic cathedral

Photo: © Aurélien Letouzé

As work progressed, archaeologists revealed the remains of a first-century building beneath the Soufflot crypt; excavated more than 1,000 sculpted fragments of the rood screen destroyed in the 18th century; and identified over 100 burials of both laypeople and clergy. Significantly, they also found two lead coffins in the transept—a place of honour for burial. One of these coffins contained the remains of Canon Antoine de La Porte, who died in 1710 and was identified by a plaque on the coffin lid. The other body was anonymous, but has since been identified as Joachim du Bellay, a 16th-century poet and one-time canon at Notre Dame.

“We identified a deceased male between 30 and 40 years old, who had been autopsied and showed bone and meningeal lesions caused by tuberculosis,” says Eric Crubézy, a professor of biological anthropology at the University of Toulouse III-Paul Sabatier, who studied the body. “These findings form a set of arguments pointing towards Joachim du Bellay. Indeed, individuals buried in the cathedral within this age range were rare, and the probability of finding such lesions was even rarer. All these elements strengthen the hypothesis of an identification with Joachim du Bellay, whose biography we have re-examined.”

Researchers made discoveries above ground too. The fire revealed previously unknown iron elements in the cathedral’s structure, studied by the metal working group, while the wood working group has examined the roughly 10,000 pieces of the building’s burned wooden roof to understand more about its assembly and construction, and even to reconstruct France’s climate in the Middle Ages. The stone working group, meanwhile, gained valuable insights into the methods used by medieval stonecutters.

“The fire had also caused some of the vaults to collapse, making it possible to examine them ‘from the inside’,” Gallet comments. “Some surprising discoveries were made, such as the very thinness of the vaults, the presence of hundreds of masons’ marks, and the remains of one of the 12th-century oculi [circular windows] in the chevet [eastern end]walls, although these oculi were thought to have been removed in the 13th century, which will allow us to better reconstruct the aspect of Notre-Dame in its original 12th-century state.”

These discoveries confirm the deep knowledge of the medieval stonecutters and masons, Gallet says, but shows that they were experimenting too. In the nave, the stonecutters appear to have hesitated when coordinating the ribs that support the vaults, for example. Once all this data has been digested and cross-referenced with the results from the other working groups, experts will no doubt need to revise the detailed chronology of the cathedral’s 12th and 13th century construction phases, Gallet adds.

“The most surprising thing is to be able to discover so many new things about a cathedral that is undoubtedly the most famous in the world, and to realise that despite its fame, Notre-Dame still retains some of its mystery,” Gallet says. “What’s also surprising is to realise that the construction is full of approximations and irregularities, even though it is considered to be the epitome of perfection in Gothic architecture.”