Hidden above the stone vaults of Notre-Dame de Paris, the 13th-century timber structure that once supported the cathedral’s steep lead roof was so extensive it was known as “the forest”. When the cathedral caught fire in 2019, the flames spread quickly through the lattice of oak beams, each one hewn from an individual tree by medieval carpenters. Around two-thirds of the roof was destroyed in the blaze.

By March 2024, the entire roof frame—la charpente in French—had been identically reconstructed by a small army of 21st-century carpenters trained in the traditional technique of working freshly harvested “green wood” by hand with an axe. (This time, however, the frame is protected against fire risks by an automatic misting system, thicker roof battens and fire-resistant trusses separating the spire from the nave and choir on either side of it.)

After generations of mechanisation, this ancient skill had almost disappeared in France when an association called Charpentiers Sans Frontières (Carpenters Without Borders) began promoting its revival in 1992. The movement’s workshops now attract volunteers from around the world. Among their members are father and son Rémy and Loïc Desmonts, whose specialist family business in Normandy shared the winning bid to restore Notre-Dame’s charpente with Ateliers Perrault, a large carpentry company near Angers with a track record of restoring historic monuments.

The workshops united in 2022 when the public contract was jointly awarded for the reconstruction of the wooden roof frames atop the nave and the choir. More than 60 carpenters joined the project, including a number of international recruits through Charpentiers Sans Frontières. Kitted out with custom-made axes, they followed Ateliers Desmonts’ approach of putting “the hand and the person at the heart of the work”, as Loïc describes it. With the eyes of the world on Notre-Dame, “we wanted to share this project with people abroad who love our heritage as much as we do and who also have the savoir-faire,” he says.

Rebuilding Notre-Dame’s “forest” also meant selecting 1,300 oak trees from across France that were “as close as possible to those of the 13th century”, that is, “very straight and very slender”, according to Desmonts, with “no defects”. Jean-Louis Bidet, the technical director of Ateliers Perrault, remembers the rush to harvest the trees in autumn so the carpenters could begin squaring the green wood from “dozens of truckloads” before the end of 2022.

The precise measurements of the 13th-century charpente had been fully documented, thanks to research conducted in 2014 by a pair of architecture students, Rémi Fromont and Cédric Trentesaux. (Fromont is now one of three chief architects for historic monuments supervising Notre-Dame’s restoration.) Each triangular truss is different, “whether in the nave or in the choir”, Desmonts explains, so an identical reconstruction required “a significant amount of work for the design office and also for the teams on the ground”.

The workshops’ traditional manual skills were guided by digital design tools that are “at the heart of the project across all the trades at Notre-Dame”, Bidet says. Computer modelling made it possible to calculate the resistance of the green wood, which will lose mass over time as it dries. The results predict that the new charpente will endure for several centuries into the future, just like the old one.

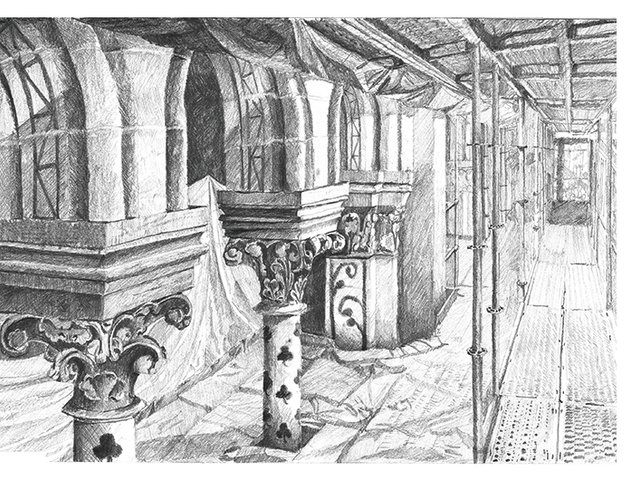

By mid-2023, the workshops had assembled the trusses to their full 10m height, as a dress rehearsal for their installation by crane on top of the cathedral. Give or take a few adjustments on site, Bidet says the final phase of the reconstruction at Notre-Dame went smoothly. The carpenters celebrated the completion of their work in January and March 2024 with another tradition: laying a bouquet of flowers on top. The gesture marked a point of collective pride for the teams who participated in “this fabulous human adventure”, Bidet says.

Desmonts recalls the emotion of seeing “everyone gathered around this element that is bigger than all of us”. Released from the hands of the carpenters, the charpente has again returned to being a “timeless” part of the fabric of the cathedral “that has its own identity and belongs to the place”.