Leonardo da Vinci’s Burlington House Cartoon, which will soon be the centrepiece of an exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts (RA) in London, originally hung close to the Mona Lisa in the artist’s studio. Coming on loan from the National Gallery, this impressive large drawing will have its own room in the RA’s Michelangelo, Leonardo, Raphael: Florence, c. 1504 (9 November-16 February 2025).

The cartoon, nearly 1.5m high and drawn on numerous sheets of paper stuck together, depicts the Virgin and Child, with St Anne and the infant St John the Baptist. It is the only surviving large-scale drawing by Leonardo and is among the finest works on paper to survive from Renaissance Italy.

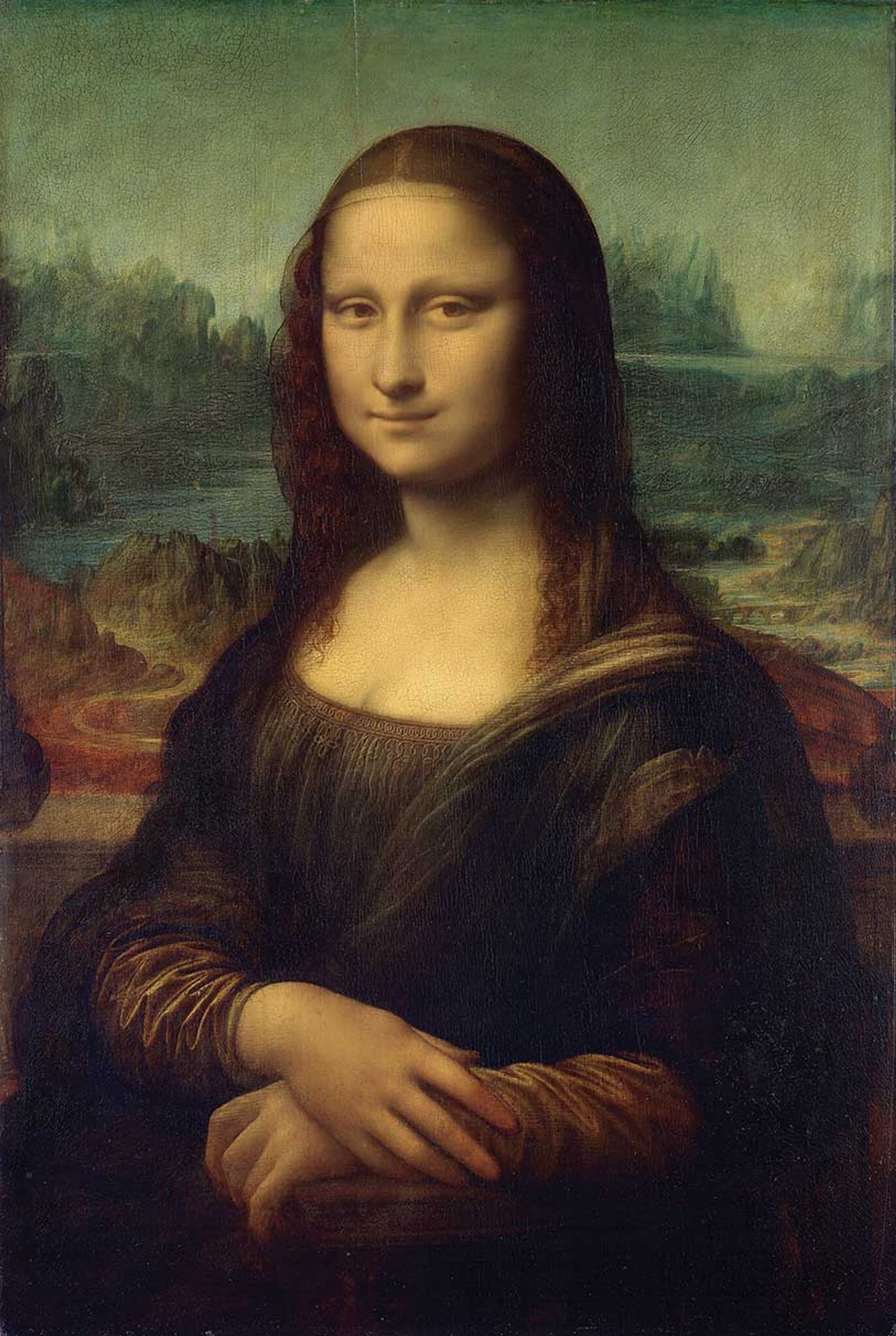

Superficially the Burlington House Cartoon and the Mona Lisa could hardly be more different. One is a colourful oil painting, the other a sober charcoal drawing. One is a flattering portrait, the other a spiritually-charged devotional work. The cartoon is nearly four times larger than the painting, in area.

Per Rumberg of the National Gallery believes the Burlington House Cartoon hung in Leonardo's studio with the Mona Lisa

Louvre Museum /C2RMF

What they do have in common, as the exhibition curator Per Rumberg explains, is their background landscapes. It is intriguing to think of the Mona Lisa (1503-19) at Leonardo’s side during the two years he was working on the drawing.

Cartoon as ‘presentation drawing’

A key point about the Burlington House Cartoon is that it was not actually a functional cartoon, a sketch to be used as the basis for another finished work of art. Rumberg believes that it was instead an independent “presentation” drawing for the centre of an altarpiece made to impress a potential patron, the Florentine government, known as the Signoria.

The cartoon was probably drawn considerably later than has usually been assumed. Until recently art historians believed that it had been done by Leonardo in 1499-1500 in Milan. But according to Carmen Bambach, a Leonardo specialist at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, it was drawn in 1506-08, a later dating basically accepted by the RA’s curators.

Rumberg is now positing that Leonardo drew the work to show the design for the centre of a huge altarpiece in the newly built council chamber, the Sala del Gran Consiglio, in what is now called the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence. St John was the city’s patron saint and St Anne was also associated with the republic. These two saints rarely appear together in Italian art of the period, so this is strongly suggestive of a Florentine connection.

The council chamber altarpiece had originally been commissioned in 1498 from Filippino Lippi, but he died in 1504 before he had even started it. Leonardo’s submission, in around 1507, was rejected, probably because of his reputation as an artist who delayed completing his work. Rumberg admits that he had “a track record for not finishing things”.

In 1510 Fra Bartolommeo was given the commission, but he got no further than making a full-size monochrome underpainting (now at the Museo di San Marco, Florence) for the uncompleted altarpiece. Fra Bartolommeo’s underpainting is on a panel nearly 4.5m high and in his composition the four figures of the Virgin and Christ Child, St Anne and St John are almost the same size as those of the Burlington House Cartoon. With the fall of the Florentine Republic in 1512, Fra Bartolommeo’s project was abandoned.

Although Leonardo’s attempt to win the commission had failed, his cartoon had an immediate impact. As Rumberg puts it, it was unveiled in a “one-picture blockbuster exhibition” in Florence, probably in 1507. Rumberg cites Giorgio Vasari, the 17th-century art historian, who wrote that Leonardo exhibited a cartoon. “Men and women, young and old, continued for two days to flock for a sight of it to the room where it was, as if to a solemn festival, in order to gaze at the marvels of Leonardo, which caused all those people to be amazed,” he wrote.

Until now this event has been associated with another lost Leonardo cartoon. But Rumberg is convinced that this passage refers to the Burlington House Cartoon. He believes that the spectators would have been astonished by the delicate modelling of the faces.

At Leonardo’s death in 1519 the cartoon probably passed to his close artist friend Francesco Melzi. It then went to the painter Bernardino Luini and the sculptor Pompeo Leoni. In 1614 it was acquired by the aristocratic Milanese collector Galeazzo Arconati and later passed to the Sagredo family in Venice.

How the cartoon came to London

The cartoon was bought in Venice in 1762 by the Scottish brothers John and Robert Udny. By 1779 it had entered the collection of the RA and in 1868 it was moved to its new home in Burlington House, in Piccadilly.

In 1962 the RA faced a funding crisis and, as a last resort, it sold the cartoon to the National Gallery for £800,000. There it was vandalised in 1987 when a man took a shotgun into the gallery and shot the Leonardo Cartoon at close range. This damage was carefully repaired by conservators.

Since its arrival at the gallery, more than 60 years ago, the cartoon has been lent only twice, on both occasions to the Musée du Louvre in Paris, in 2012 and 2019.

Per Rumberg

Courtesy Per Rumberg

Rumberg has a foot in both camps in London. It was when he was a curator at the RA that he planned the exhibition, so it fell upon him to formulate the loan request. Then in November last year he moved to the National Gallery to become the head of its curatorial department, so he is now responsible for the loan to the RA. Rumberg has continued as the RA exhibition co-curator, along with Scott Nethersole of Radboud University in Nijmegen, the Netherlands.

In the RA exhibition the cartoon will play a starring role, being presented as the sole object in the central gallery of the three-room show, in an attempt to recreate the cartoon’s original display in Florence in 1507. It will also be a homecoming, with the Burlington House Cartoon returning to the very building that gave it its name.