Total star rating: ★★★★

The works: ★★★★½

The show: ★★★½

London has served up a sumptuous Italian Renaissance feast this winter, with two exhibitions highlighting the role of drawing in the creative process. The Royal Academy of Art’s (RA) exhibition Michelangelo, Leonardo, Raphael: Florence, c. 1504, the subject of this review, takes the rivalry between three titular titans as its focus, zooming in on the pivotal years at the start of the 16th century. Drawing the Italian Renaissance (until 9 March) at the King’s Gallery, on the other hand, presents a dazzling collection display of a kind that perhaps only the Gallerie degli Uffizi in Florence can rival.

At the King’s Gallery, across a beautifully choreographed selection of drawings, ranging from life studies to full-sized working “cartoons”,the sheer virtuosity of the Renaissance Old Masters holds sway. The Royal Collection’s 158 exhibits inevitably make the RA’s show look sparse in comparison. But what it lacks in quantity, with 40 or so exhibits, the RA more than makes up for in academic stimulus, graphic excitement and provocation.

Its exhibition revolves around three exquisitely lit masterpieces, all made in Florence in the first decade of the 16th century and executed in different mediums: the Royal Academy’s own Taddei Tondo, Michelangelo’s bold, avant-garde experiment in sculptural relief; Leonardo da Vinci’s monumental drawing The Virgin and Child with St Anne and the Infant St John the Baptist (the so-called Burlington House Cartoon, on loan from London’s National Gallery, which acquired it from the RA in 1962); and Raphael’s oil, The Bridgewater Madonna (on loan from the National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh). All of these can normally be viewed, free of charge, in British collections. But the opportunity to see them united by a strong curatorial proposition and with a tremendous supporting cast of drawings, is well worth the admission.

Leonardo's Burlington House Cartoon

© David Parry/Royal Academy of Arts

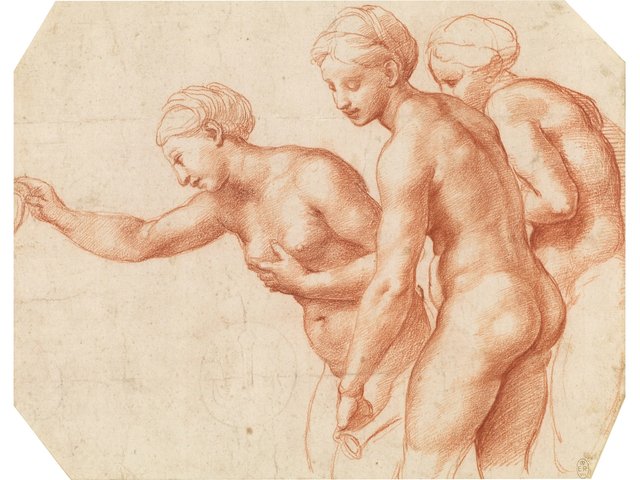

The show unfolds in three episodes across three rooms. The first focuses on Michelangelo’s ravishing (if unfinished) Taddei Tondo (around 1504-05), made at the age of around 30. Embodying all the energy of chiselling into stone, the apocryphal story of the Christ Child’s encounter with the infant St John, during the holy family’s flight into Egypt, emerges from a hunk of white Carrara marble. In this room, we also come across the 21-year-old Raphael, newly arrived in Florence and rapidly absorbing Michelangelo’s inventions. We see him riffing on the Taddei Tondo’s straddling Christ Child and witness the moment he subtly makes the Madonna-and-Child theme his own.

A few weeks earlier, the 54-year-old Leonardo had participated in a 30-strong committee of leading artists, sculptors and architects, tasked with advising where Michelangelo’s brand-new colossal statue of David should be placed. One can imagine the worldly Leonardo, breaking off temporarily from painting the Mona Lisa (begun in 1503) to contemplate the most convenient setting for Michelangelo’s giant nude. David (1501-04) makes an appearance in the form of a drawing by that magpie Raphael, who, with a quick eye and a light touch, sketches it from behind, elegantly reducing the over-sized hands in the process.

Old Master battle

The final room focuses on the famous head-to-head confrontation between Leonardo and Michelangelo, embodied in their unrealised efforts (around 1503-06) to create two battle murals for the Florentine Republic’s great Sala del Gran Consiglio. Their two designs, each commemorating a great Florentine victory—Michelangelo, the Battle of Cascina; Leonardo, the Battle of Anghiari—are known through copies, both of which feature in the show. But it is the preparatory drawings and related studies that provide the most staggering evidence of what the artists had in mind, from Michelangelo’s naked bathing soldiers, surprised by the call to arms, to Leonardo’s frenzied melding of men and horses, grotesquely distorted by the ferocity of war.

In the central room, Leonardo’s enormous and spell-binding Cartoon inhabits a chapel-like space of its own, and this is where we encounter the curator Per Rumberg’s new hypothesis, which provides the scholarly underpinning of the show. For Rumberg, the excitement of the horizontal pose of Leonardo’s Christ Child has been overlooked; it is only now that one can see how powerfully it corresponds with Michelangelo’s Taddei Tondo. Rumberg also controversially proposes that it was designed for the same hall as the battle murals, marking the climax of one phase and the transition to the next. Rumberg’s thesis requires the Leonardo Cartoon to be dated around 1506-08 rather than the earlier date of around 1501, favoured by some previously.

Which came first?

Rumberg’s intervention changes the course of who was influenced by whom. Who, in effect, fired the starting gun for what we now term the “High Renaissance”, injecting that new “modern” sense of dynamism? Which came first, Michelangelo’s horizontal twisting Christ Child—an ancient sleeping Cupid, rudely awakened by a flapping bird and intimations of sacrifice—or Leonardo’s Christ Child wriggling from his mother’s arms? Michelangelo had a slightly static start, still evident in his statue of the Bruges Madonna, and lingering in the academic stiltedness of his Battle of Cascina bathers. Yet the energy he generates through conflicting emotional impulses and physical torsion creates a vital force. Certainly, Leonardo was innovative; his Cartoon has the Christ Child swooping across the composition like a flying soul, so much so that the vertical of St Anne’s outlined hand, pointing upwards, has to be introduced to check his flight. We see the circular welding of weighty figures, the dark mystery of suggestion, and the agitation generated by sketchy feet and hints of water rippling over stone.

Giorgio Vasari, writing his Lives of the Artists in 1550, saw the great emergence of antique Roman models as the tipping point for the birth of this new heroic style. And perhaps the one regret of this show is that the animating spirit of the antique is not conjured up more vividly.

But the show is not, Rumberg argues, about art history. It is about visual analysis. The formal pivot is Michelangelo’s circular Taddei Tondo, and the actual point of “revolution” or central axis, in both the Tondo and Leonardo’s Cartoon, is the stomach of the Christ Child, from which everything, including man’s destiny, spins. For Michelangelo, this is also the point from which everything pushes outwards, in a strange and original artistic departure. Leonardo takes this revolution further, working up his compositions from the centre outwards, creating a force field that sucks the viewer into the depths of the mystery, or the furious heart of the action, depending on his theme. Meanwhile, Raphael tames and refines. These are forces forever to be reckoned with.

What the other critics said

In his four-star review in The Guardian, Jonathan Jones writes that the exhibition “makes little attempt to bring 'Florence c. 1504' to life … I wanted wall-filling photos, digital projections and hi-tech sculptural and architectural simulacra. No. This is an academic show.” Laura Freeman in The Times concurs: “It is scholarly, particular and chock-full of wonder, but I could have done with just a touch more exposition and hand-holding.” Emily LaBarge in The New York Times comments on the show’s academic approach and visual focus: “If this elegant, scholarly exhibition traces an anxiety of influence, it also shows that imitation offers artists a chance to hone individuality.”

• Michelangelo, Leonardo, Raphael: Florence, c. 1504, Royal Academy of Arts, London, until 16 February 2025.

• Curators: Scott Nethersole and Per Rumberg.

• Tickets: 19-£21 (concessions available).