With a cigar in hand and sporting a giant handlebar moustache, the late artist LeRoy Neiman captured the public imagination in the US from the 1960s onwards. Neiman was known for his paintings of sports stars, such as the boxer Muhammad Ali, and Playboy illustrations—he was described as Hugh Hefner’s court painter—but was shunned by critics and curators. “Neiman was not an artist whom anyone in what I will call the serious art world ever cared about,” wrote Ken Johnson in an obituary in The New York Times (the artist died aged 91 in 2012).

In a new biography, the writer Travis Vogan, a professor of journalism, mass communication and American studies at the University of Iowa, presents the Life of America’s Most Beloved and Belittled Artist (the book’s subtitle), providing a new take on Neiman’s status and achievements.

“Despite Neiman’s fame and pervasiveness during his lifetime, his story has not really been told—at least not in a careful or serious way,” Vogan says. “I feel that Neiman provides an illuminating entry point into 20th-century America and the culture that marked it. He seemed to be everywhere and rub elbows with everyone, from Frank Sinatra to Muhammad Ali to Jimmy Carter. And he created works of all these figures and the scenes in which they circulated.”

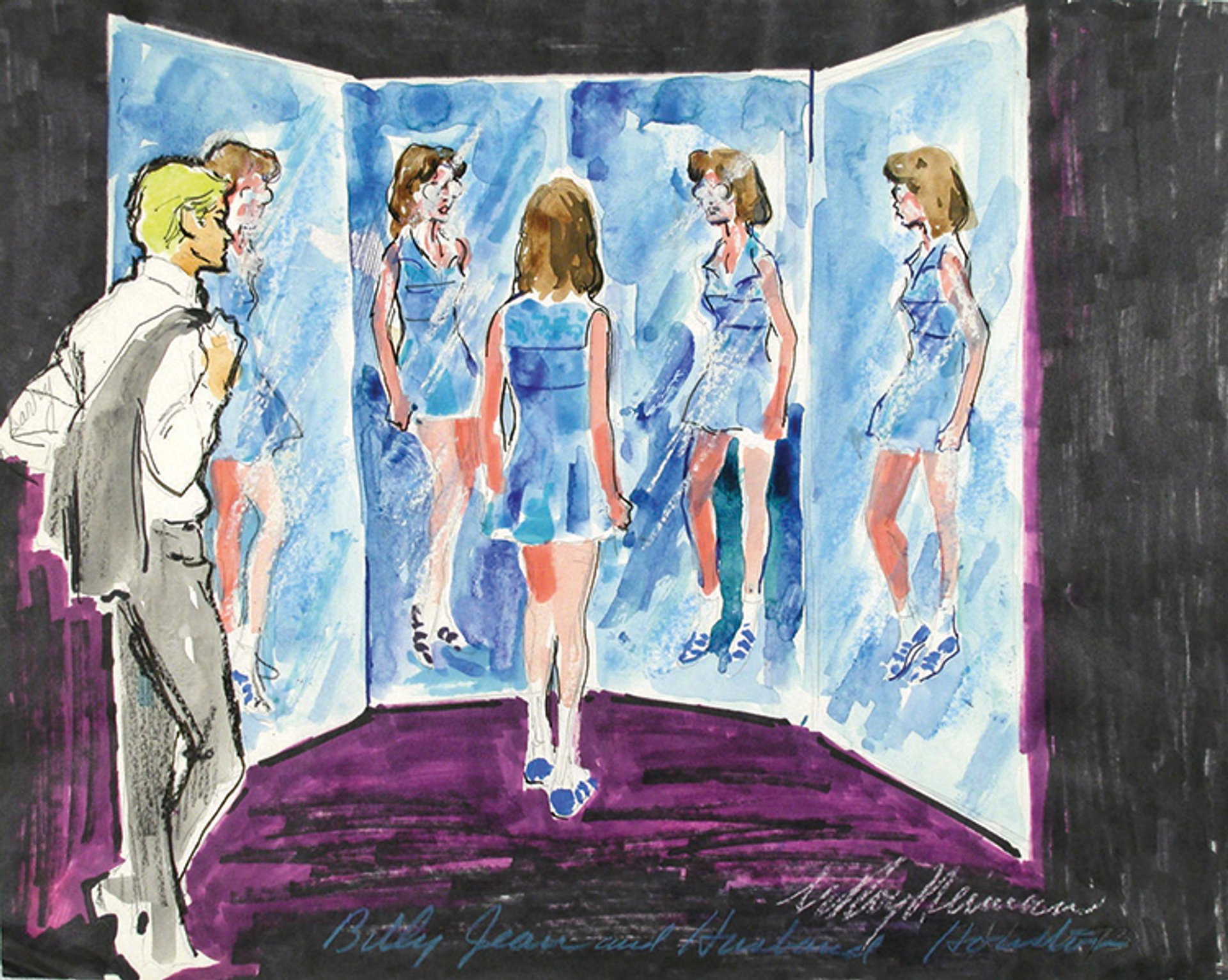

Neiman’s painting of Billie Jean King in 1973, at the height of the tennis star’s career © 2023 LeRoy Neiman and Janet Byrne Neiman Foundation/ARS

Neiman was born and raised in Saint Paul, Minnesota, spending his youth “on the streets donning ill-fitting hand-me-downs while playing sandlot football, ducking bullies, and drawing”, writes Vogan. He dropped out of high school, joining the US Army in 1942, where he worked as a cook and painted sets for Red Cross shows as well as creating “bawdy murals” on the walls of Second World War mess halls, according to the LeRoy Neiman Foundation, which oversees his estate. In the late 1940s, he attended the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and studied liberal arts at the University of Illinois and DePaul University. Neiman’s big break came in 1954 when he met Hugh Hefner, who had just launched a new men’s magazine called Playboy. In 1957, he created a logo for the magazine called Femlin, which the foundation describes as a “sexy female sprite”.

Throughout the 1960s, Neiman’s profile soared via a number of important projects such as capturing the Democratic National Convention in 1968 in a series of paintings, along with his appointment as the artist-in-residence for the New York Jets football team. He also launched art classes in the Atlanta Poverty Program. But most of his works and projects have gone under the art world radar, among them his images of the signing of the Egypt-Israel peace treaty at the White House in 1979.

“I think to an extent some of this [work] was overshadowed by his more visible and commercially successful work, especially the material for Playboy and the works about sport,” Vogan says. Neiman even partnered with the fast-food chain Burger King for the 1976 Montreal Olympics, giving away posters of his sports paintings with meals.

The art of business

Was he as much a businessman as an artist? “Definitely. But he did not see these as conflicts,” Vogan says. “He believed he could be a legitimate artist while producing work for a fast-food restaurant or a commercial television network. Many disagreed and viewed him as an uncritical shill or pitchman for his clients. Neiman always insisted that he had complete artistic autonomy when doing commissions and that he painted whatever struck his fancy.”

However, Vogan adds, this claim is “often hard to believe since his commissioned works tended toward the celebratory. He was a hustler, for sure. But the art world is full of them. In a way Neiman was more honest than most, who tend to deny their economic motives”.

And the art itself? Neiman once described his technique as a singular form called “Neimanism”. Vogan argues that it combines Abstract Expressionism with Impressionism plus dashes of Fauvism and American Realism. “He brought a number of approaches together. Many fans and consumers loved this, but it often rankled critics who thought he created watered-down and easily digestible versions of these recognised approaches.”

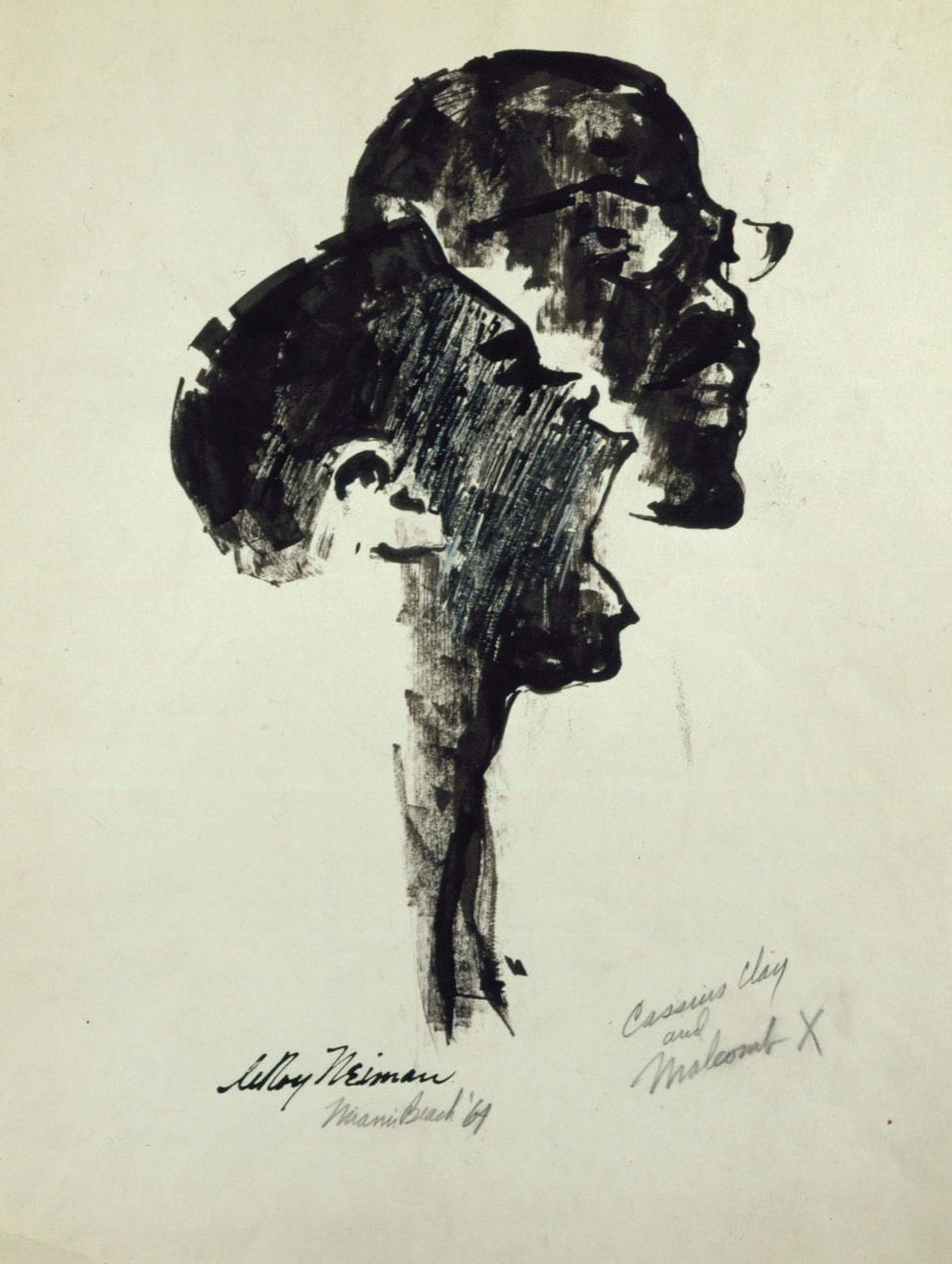

Neiman's Muhammad Ali and Malcolm X (1964) © 2023 LeRoy Neiman and Janet Byrne Neiman Foundation / ARS, NY

The book took around five years to complete, says the author. “As someone who was very concerned about his legacy, Neiman kept meticulous records,” Vogan says. “The Smithsonian [Institution] has about 85 boxes of his materials. His foundation has much more material that is not publicly available, but that they kindly let me consult. I found his personal correspondences to be the most interesting. They demonstrate a sweetness, vulnerability and humanity that was not always apparent in his swashbuckling public persona, which was carefully controlled.”

Neiman continued to make waves into the 21st century. In 2002 he travelled to Havana with members of the US Congress and the press to meet with the Cuban president Fidel Castro, who sat for several drawings. In 2005 LeRoy and his wife Janet Neiman donated $3m to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. But on his death, press reports still hailed him as “the artist critics loved to hate”.

Vogan says he hopes the book will lead to a re-evaluation. “I think there is a lot of value in Neiman’s work. It sheds fascinating light on the culture of this time. But more than that, it speaks to the unsteady relationship between art and popular culture. Why do we tend to think that commercial art is illegitimate? How do these understandings of art limit certain peoples’ ability to understand and appreciate art? What does one’s taste in art say about how they imagine themselves and their status in society?”

• Travis Vogan, LeRoy Neiman: The Life of America’s Most Beloved and Belittled Artist, University of Chicago Press, 416pp, $35 (hb)

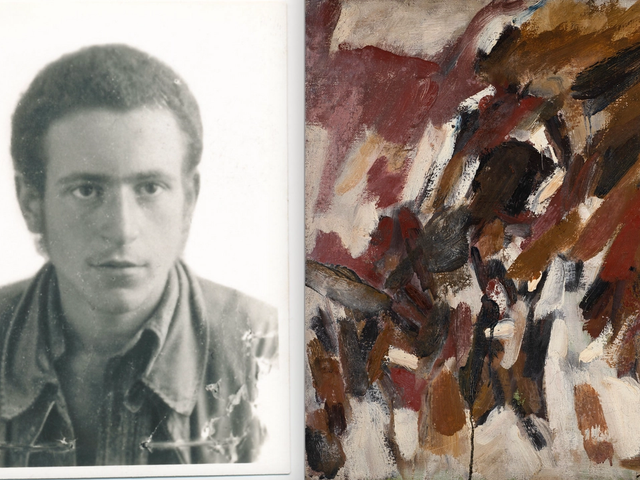

![The artist in 1969: “a hustler, for sure… but Neiman was more honest than most [in the art world]”

Portrait: Courtesy of LeRoy Neiman and Janet Byrne Neiman Foundation](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/cxgd3urn/production/bc780466b49fe490214dfa674f08f2d1517404a6-827x1222.jpg?w=1200&h=1773&q=85&fit=crop&auto=format)