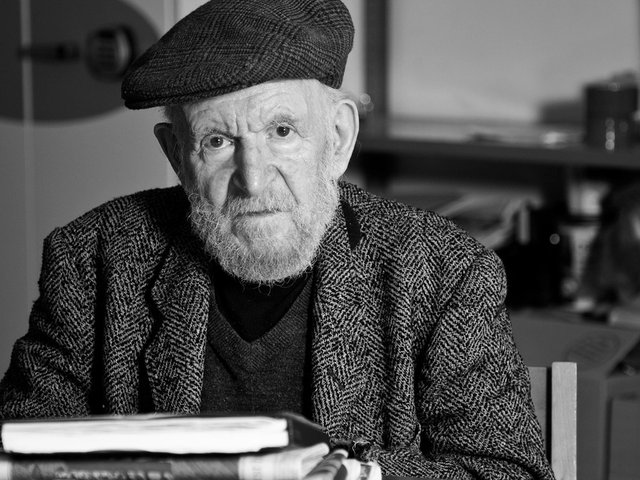

The artist Gustav Metzger, who died in 2017 aged 90, was a leading proponent of the auto-destructive art movement. A lifelong activist, Metzger was “one of the truly radical artists of the 20th century”, said Hans Ulrich Obrist, the artistic director of London’s Serpentine Galleries, at the time.

A new exhibition at the Ben Uri Gallery and Museum in London and accompanying book examine the formative years of Metzger who was born in Nuremberg, Germany, to Polish-Jewish parents in 1926, and came to Britain on the Kindertransport (the mass rescue movement of children) in 1939. Becoming Gustav Metzger: Uncovering the Early Years (1945-59) has been organised by the Ben Uri Research Unit in partnership with the Gustav Metzger Foundation in London.

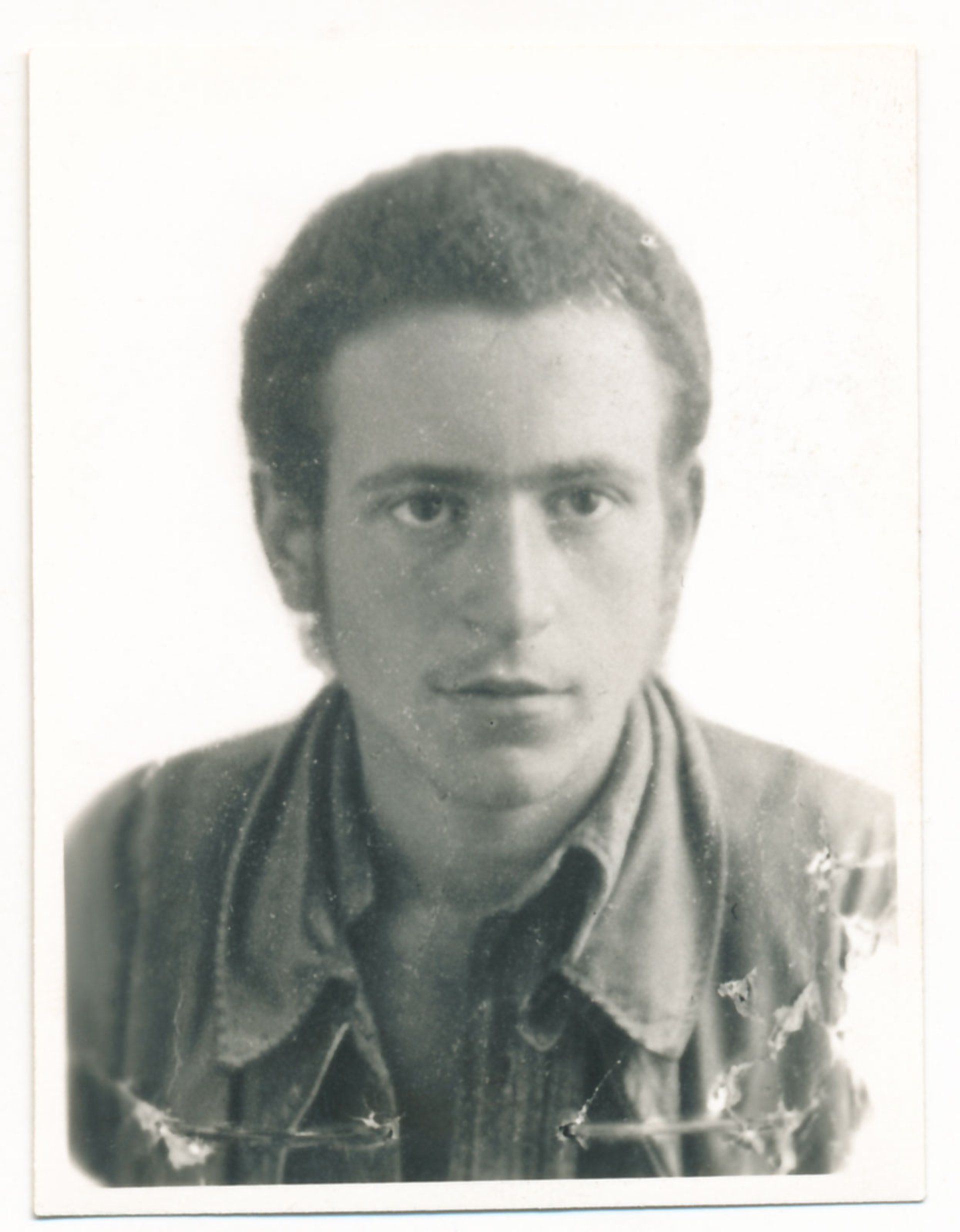

A passport photo of a young Gustav Metzger Courtesy of the Gustav Metzger Foundation

“Both [the exhibition and book] showcase rarely seen drawings and paintings which chart Metzger’s artistic journey from figuration to abstraction prior to the development of his later radical, auto-destructive practice,” writes the museum director Sarah MacDougall, in the publication’s introduction. Below are three key takeaways from the book.

Gustav Metzger's Eroica, Funeral March (1946) Courtesy of The Gustav Metzger Foundation; image © Justin Piperger

Metzger made a substantial body of paintings which lay hidden in a relative’s attic

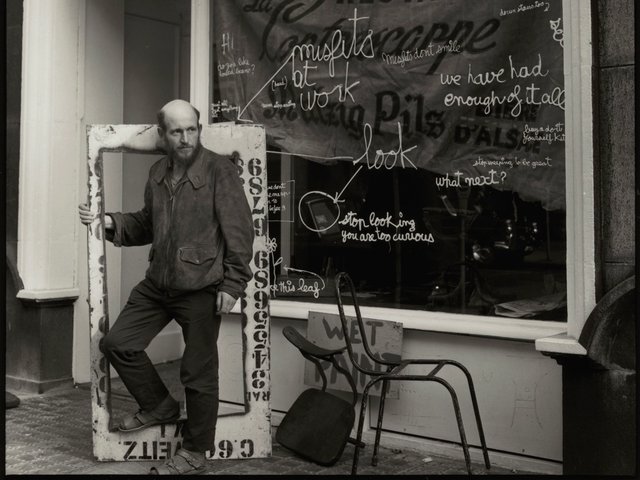

Most of Metzger’s drawings and paintings from this crucial early period prior to his auto-destructive innovations have never been exhibited and also tend to be omitted from any account of his canon. The former Tate curator Andrew Wilson outlines how in advance of the opening in 2009 of a solo exhibition of his work at the Serpentine Gallery in London, Decades 1959-2009, Metzger decided to retrieve from the attic of his auntie in north London work he had kept in storage since 1965. A large proportion of paintings and drawings he produced between 1945 and the early 1960s subsequently came to light 11 years ago.

Wilson also discusses an important, little known show of Metzger’s works in September 1960 in London. “The Temple Gallery show was a carefully paced ‘retrospective’. Beginning with his earliest fully conceived statements as an artist in 1945 and 1946, oscillating between expressionism and symbolism, the exhibition included: Trees (1945), Eroica, Funeral March (1946)…. paintings whose size and ambition signalled an intended, declarative function. The symbolism of Paul Gauguin merges with a Futurist sensibility, framed by an already grounded pull of aesthetics and tradition,” Wilson says.

The show included a drawing of the artist Frank Auerbach, entitled Head of Auerbach (around 1952) and listed as ‘drawn by David Bomberg and Metzger’. Auerbach, however, denies ever having sat for Metzger, according to a footnote in the book.

Metzger's Head of a Man (around 1951-53) Courtesy of The Gustav Metzger Foundation; image © Justin Piperger

Metzger was influenced by—and later fell out with—his mentor, the artist David Bomberg

In 1945, Metzger enrolled in evening life classes at the Borough Polytechnic taught by David Bomberg. Nicola Baird, the publication editor, describes Metzger’s first impressions of the influential British painter. Metzger recalls: “I was introduced to drawing that was completely different to what I had been doing in Cambridge [at the School of Art], which had involved following the outline of the figure, to make a realistic interpretation. Bomberg said, ‘Forget about that! Go for the structure! Go for the centre and use the full weight of your body.’”

In the summer of 1953, Metzger was one of a small number of Bomberg’s pupils who came together to form, “not a group, but a grouping of students who would exhibit together”, known as the Borough Bottega, Baird says. But this initiative would soon fall apart.

Mathieu Copeland, who helped Metzger compile an anthology collection of his writings, says in the book that among the items found in the attic was a letter from Bomberg breaking ties with his protégé. “It is indeed a very painful letter to read,” Copeland says. “We will never know exactly what happened between the two men, but it is true that there is a definite change of tone in the letters sent by Gustav before and after that fateful correspondence dated 17 December 1953. I believe that this is the only surviving letter that Bomberg sent, which makes it quite telling that Gustav would choose to hold on to this very one. Gustav told Hans-Ulrich Obrist that the break had to do with how he felt Bomberg was trying ‘to dominate the [Borough Bottega] ... to an extent that ... [he] could no longer accept.’”

Metzger's Homage to a Starving Poet (1951) Courtesy of The Gustav Metzger Foundation; image © Justin Piperger

How Metzger’s auto-destructive art was born

In 1959, Metzger wrote in the first of three auto-destructive manifestoes that “self-destructive painting, sculpture and construction is a total unity of idea, site, form, colour, method, and timing of the disintegrative process”. Stephen Bann, emeritus professor at the University of Bristol, describes the artist’s initial experimentation and why the artist’s auto-destructive work is an important form of kinetic art (Bann stresses that Metzger’s art should be discussed in the “same company as the magnetic sculptures of Takis and the bubble machines of David Medalla”).

“The new medium that most strikingly embodied his shift involved treating liquid crystals to create a kinetic spectacle,” Bann writes. “I do…. preserve a vivid memory of being invited by Gustav to a house in Great Russell Street, near the British Museum, where he activated one of his crystal slides in front of a blazing gas fire. This episode, which might well have been in 1966, showed off the medium which was perhaps his most original contribution.”

• Becoming Gustav Metzger: Uncovering the Early Years 1945-59, edited by Nicola Baird, Ben Uri Research Unit, 133pp, £20.00 (hb)