The rehabilitation of the late US artist Lee Krasner (1908-84) continues apace with the publication of a new long-form essay by the art critic and poet Carter Ratcliff titled Lee Krasner: The Unacknowledged Equal. The new research, published by the New York-based Pollock-Krasner Foundation, provides insights into the evolution of Krasner’s work and relationship with her husband Jackson Pollock—“definitively bringing her out of Pollock’s shadow”, according to a foundation statement.

Krasner’s legacy is in the spotlight again, especially in Europe, after a major touring exhibition left visitors wondering why her art is only now being reassessed on its own terms. (The show opened at London’s Barbican last year before travelling to the Schirn Kunsthalle in Frankfurt and Zentrum Paul Klee in Bern; it is due to open at the Guggenheim Bilbao next month). Crucially, Ratcliff argues that Krasner was as much the inventor of “allover” painting as Pollock (the all-over approach pioneered by the Abstract Expressionism movement involves covering the entire canvas with paint, rejecting traditional composition methods).

The essay is available to download for free; the print version of Lee Krasner: The Unacknowledged Equal is due to be released later this year. Here are some takeaways from Ratcliff’s analysis.

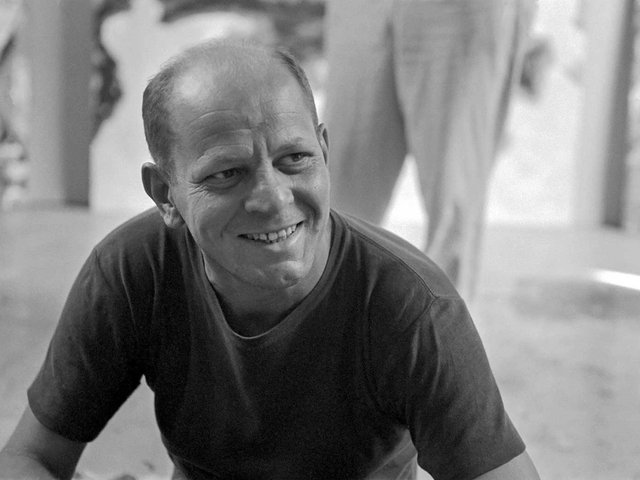

Lee Krasner photographed with her works in The Springs, NY © 1980 Kelly/Mooney © Pollock-Krasner Foundation, ARS

Lee Krasner’s role in developing “allover” painting was as instrumental as Pollock’s

Ratcliff believes that Krasner’s role in developing “allover” paintings has never been fully acknowledged, with the credit for this innovation going to Pollock. Krasner began making works in this mould in the late 1940s in parallel with her husband at their house in the Springs, a hamlet near East Hampton on Long Island.

“Isn’t it possible that either Krasner or Pollock painted an “allover” image some time in 1946, saw on his or her own that it had potential and proceeded from there?” Ratcliff writes. He adds:

Art critics and historians have been telling this story for more than seven decades. Naturally, they cast Pollock as the star, the heroic innovator, with Krasner tagging after in the supporting role of his first follower. As plausible as it seems, this scenario ignores an inescapable truth: artists do not innovate in isolation.

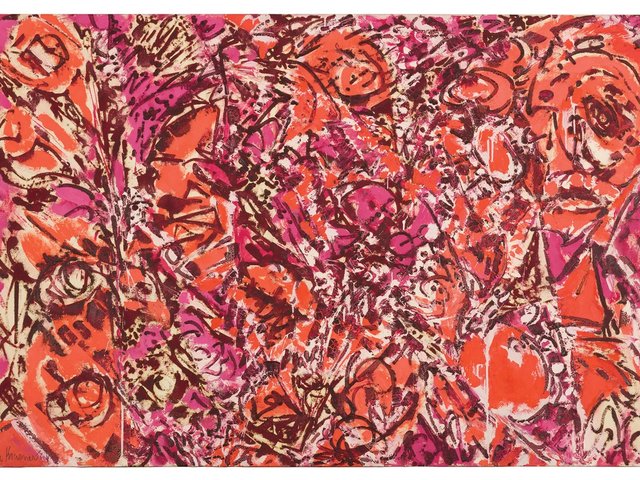

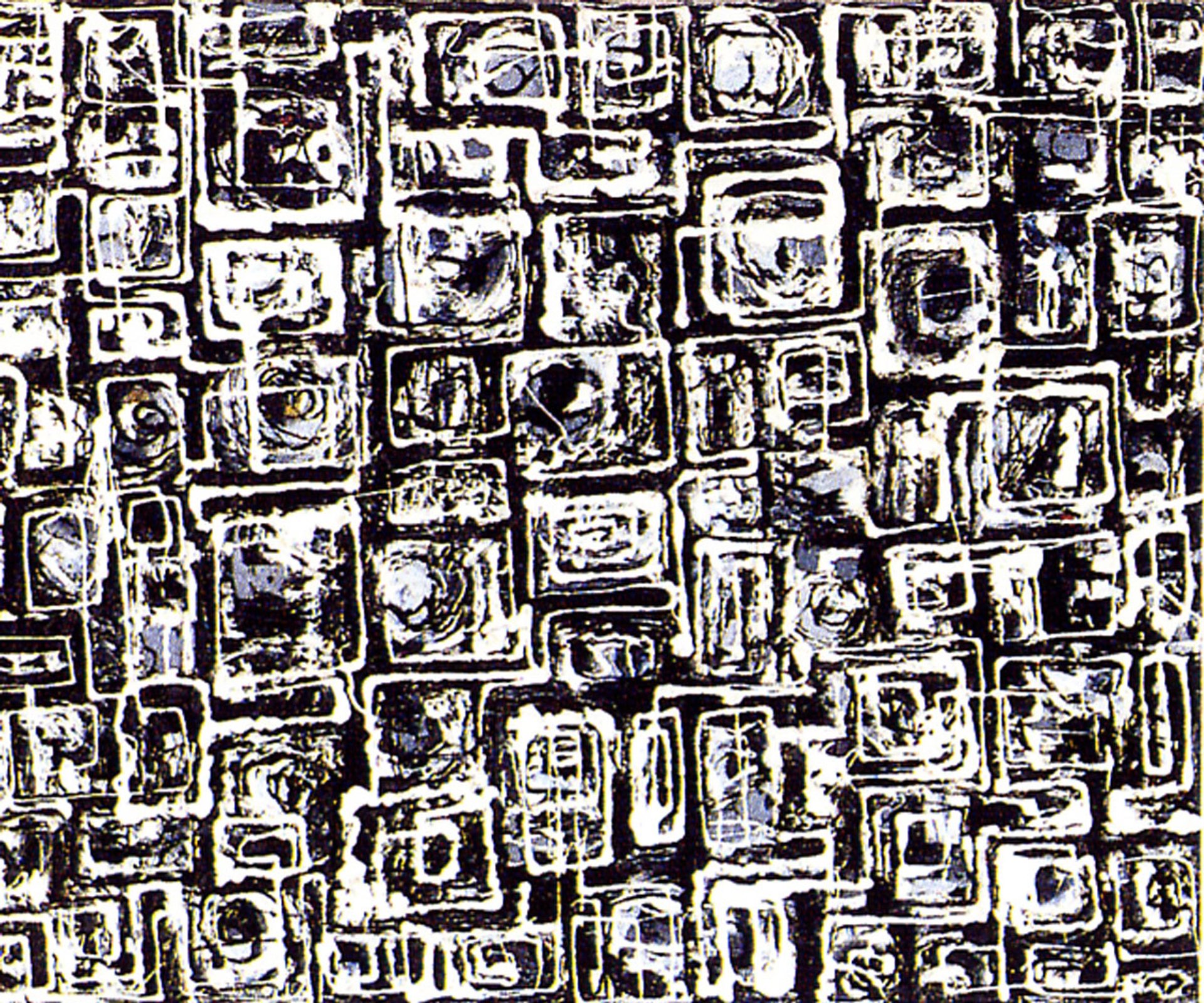

Ratcliff argues that Krasner’s works Blue Painting (1946)—which “quivers with linear drama played out against a backdrop of red and blue pigment […]”—and Image Surfacing (1945) are good examples of her first “allover” canvases, standing alongside comparable paintings by Pollock, such Shimmering Substance (1946). He develops this thesis, stating that a body of work made by Krasner in 1949, based on the principles of hieroglyphics, can also be classed as “allover” paintings, citing examples such as White Squares (around 1948) and Continuum (1947-49):

There is no focal point, no principle of containment, and no recognition of the edge as anything but a physical fact. These are not compositions but allover images, and so different from Pollock’s that only a few writers have ever applied the word to them. Krasner called them “hieroglyphic,” as good a name as any for grids inflected by flourishes of paint that come to rest at the border where writing—or calligraphy—meets painting.

Lee Krasner's White Squares (around 1948) Whitney Museum of American Art; Mr. and Mrs. B. H. Friedman. © 2020 Pollock-Krasner Foundation, ARS. Image © Whitney; Scala; Art Resource

Critic Clement Greenberg hedged his bets over the first “allover” artist

Ratcliff unpicks the renowned critic Clement Greenberg’s praise for Pollock, revealing that Greenberg also credited the little-known Ukrainian-US artist Janet Sobel with originating the “allover” technique and style. Ratcliff writes:

In 1944 Peggy Guggenheim exhibited paintings by Janet Sobel, an art-world outsider whose drip method prompted Clement Greenberg to state in 1961 that these were “the first really all-over images” he had ever seen. This was awkward because the critic had made his reputation, in large part, by glorifying Pollock as the sole progenitor of alloverness. The critic said that Pollock, too, had admired Sobel’s drip paintings, if only “furtively,” and “later admitted that these pictures had made an impression on him”.

Ratcliff’s research shows how Greenberg conveniently erased Sobel from the “allover” art historical lineage. In the footnotes, Ratcliff points out that when Greenberg first published his essay ‘American-Type Painting’ in the Partisan Review in 1955, he did not mention Janet Sobel. “She appears only in the version of the essay revised in 1961 for inclusion in Art and Culture. These revisions were subsequently dropped when the essay was included in Greenberg’s Collected Essays and Criticism, Volume 3: Affirmations and Refusals, 1950–1956, where it occupies pages 217-235,” Ratcliff writes.

“His talk of Sobel lets us surmise, at most, that he felt—for a time—the need to hedge his account of Pollock’s originality,” Ratcliff says. It is worth noting also that by the late 1930s, Krasner had developed “the best eye in the country for the art of painting”, according to Greenberg.

Lee Krasner's Sunwoman, I (1957) Courtesy of Kasmin Gallery. Photo: Diego Flores. © 2020 Pollock-Krasner Foundation, ARS

Male curators wrote Krasner out of art history

Krasner was given a big platform in 1965 when the Whitechapel Gallery in London held a major survey titled Lee Krasner: Paintings, Drawings and Collages. But critics at the time struggled with her achievements. Ratcliff says that “after praising the show in the pages of the Weekend Observer, [the critic] Nigel Gosling said, ‘I doubt that anyone would guess from [Krasner’s] paintings that they are by a woman. On the other hand, they are unmistakably American.’”

This intolerance was echoed in B.H. Friedman’s spiky introduction to the Whitechapel catalogue:

First, it must be noted that Krasner is a woman—in a field which still, even now in 1965, barely tolerates women, condescends to them with the phrase “woman painter”, as odious and pejorative as “woman writer” or “woman driver”. In her work, Lee Krasner wants to be judged—or, better, experienced—as a painter. She wants no special categories. It may even be, whether consciously or unconsciously, that this is why she took the androgynous name “Lee”.

Krasner was duly excluded from the exhibitions New York School: Paintings from the 1940s and 1950s at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 1965 and New York Painting and Sculpture: 1940–70 at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1969. “That she, a woman, was among the most important members of this triumphal generation could not be acknowledged—could not, perhaps, be imagined—by these male curators and historians,” Ratcliff concludes.