One of the largest museum and heritage projects in Rome, the National Roman Museum initiative, has launched after the Italian ministry of culture recently approved €71m in funding (giving €100m in total) for the cultural scheme encompassing four major sites in the capital: the Baths of Diocletian, Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, Palazzo Altemps and Crypta Balbi.

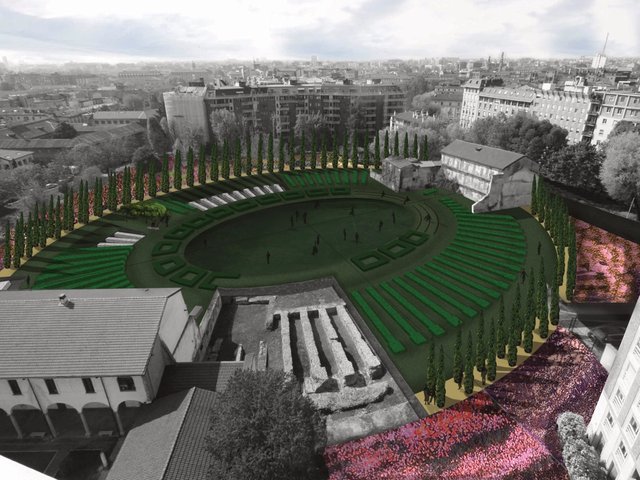

The restoration of the four sites, overhauled under a government project known as “Urbs, from the city to the Roman countryside”, will take around four years, and includes the restoration of the buildings, reorganising the museum collections and opening new exhibition spaces. The masterplan encompasses revamping the Great Halls around the basilica of Santa Maria degli Angeli in the Baths of Diocletian, one of the largest ancient bath complexes in the world, and a new display of the Boncompagni Ludovisi 17th-century sculpture collection at the Palazzo Altemps. We asked the director of the National Roman Museum, Stéphane Verger, about the radical new plans.

The Art Newspaper: How will the plan connect different parts of Rome?

Stéphane Verger: This is a project aimed not only at museum spaces, but also linked to urban redevelopment plans. I am thinking of the Termini station area, where the Baths of Diocletian and Palazzo Massimo are located and where the Municipality of Rome and Grandi Stazioni will redevelop the Piazza dei Cinquecento. The idea is to make the Baths of Diocletian an island of culture. For the Campo Marzio, Palazzo Altemps and Crypta Balbi, our plan is to enhance them within the great tourist itinerary that leads from the Trevi Fountain to the Pantheon, and from Piazza Navona to Castel Sant’Angelo and the Vatican. The Renaissance building Palazzo Altemps is on this route but is not well known by tourists.

Will the great bronze pieces such as Boxer at Rest (330-50BC) and the Hellenistic Prince (second century BC), exhibited until now in Palazzo Massimo, find a place in Palazzo Altemps?

We have thought long and hard about how to present Greek sculpture, both the originals and the Roman copies and recreations of Greek models and styles. Around this fundamental subject we want to articulate a thematic story in Palazzo Altemps, starting from antiquity, going up to the Renaissance and Baroque periods. Another of our intentions will be to tell the “biography” of the objects on display, and their long history. I’m thinking of, for instance, the Discobolus (fifth century BC), raided by the Nazis and recovered only at the end of the Second World War, a work which is currently on display at the Scuderie del Quirinale in the Arte liberata exhibition.

What will be the thematic focus in the other three locations?

The Baths of Diocletian, Palazzo Massimo and Crypta Balbi will survey the history of Rome from its origins up to the 20th century. At the Baths we will tell how the city arose from the tenth century BC up to the time of the emperor Diocletian (fourth century AD). In Palazzo Massimo, the Roman Empire will be central, while in the Crypta Balbi we will illustrate Rome today. The Crypta has a magnificent itinerary, created in 2000, which narrates the centuries-old urban stratification of Rome. The archaeological story will be reopened, the museum will be expanded and will touch upon the Modern and contemporary era.

Will more works be taken out of storage?

Thanks to the opening of new exhibition spaces we will be able to show many works, among them some unseen, from the collections of the National Roman Museum. In the seven Great Halls that we will reopen at the Baths of Diocletian, for example, there are spectacular finds last seen in the 1960s or 1970s, such as the Artemis of Ariccia, a monumental marble statue, over three metres high, based on a Greek original from the fifth century.

Is this a museum that looks to the future and its relationship with the city?

It is Rome itself that is innovative. It is often said that this city is a museum, but it is not so: it is rather a living organism which in every age has known how to reuse the past to build a new present and make it the model for its future. With this overall project we must move on two fronts: on the one hand by describing the complexity of the urban organism of Rome, on the other by placing contemporary art creations in the National Roman Museum sites in an intelligent way. In this spirit, we presented Elisabetta Benassi’s work Empire in the Crypta Balbi [in 2019]: the language of contemporary art helps to understand what urban stratification is in Rome. A museum cannot stand still, but must follow and correspond with transformations in the city.