Almost 2,000 years ago, the first Roman emperor, Augustus, proclaimed his power through an impressive building programme designed to transform his capital from “brick into marble”.

In the 1930s, Mussolini grasped the propaganda potential of Rome’s imperial architecture in a huge archaeological programme that had less to do with the recovery and preservation of antiquity than with fostering an apparent continuity between the imperial city and Fascist Rome.

Now, the mayor of Rome, Francesco Rutelli, and his Partito Democratico della Sinistra (Democratic Party of the Left) council, have endorsed a major scheme in the run-up to the millennium that will go a long way towards erasing Mussolini’s mark on the city.

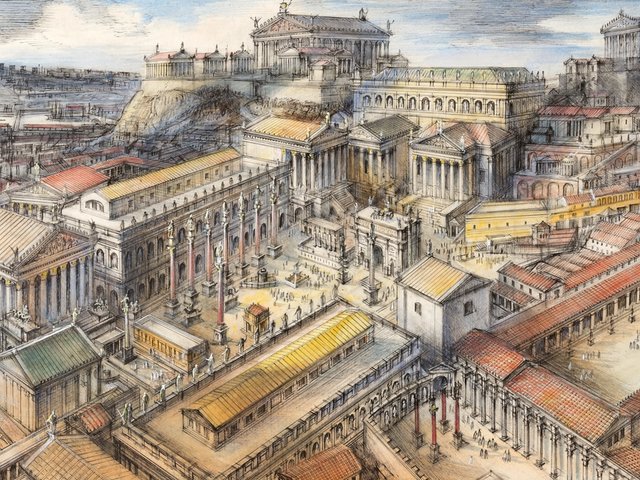

In a project that has been described by its supervisor, Professor Eugenio La Rocca, as “every archaeologist’s dream”, the imperial fora of Augustus, Vespasian, Nerva and Trajan, built in antiquity to serve as the political and commercial heart of the city, are to be excavated as far as is possible without disrupting the modern city. Ongoing excavations on the Forum of Nerva have already yielded rich finds from every era of the city’s history.

At the turn of the century, the archaeologist Corrado Ricci focused on the visible parts of Trajan’s Markets, the Forum of Augustus and a small area of the Forum of Nerva, all of them partially visible in the courtyards and cellars of a sixteenth-century residential area. At that time archaeological excavation was not contemplated because the area was densely populated.

Enter Mussolini and his team of archaeologists in 1931. In his eagerness to excavate the fora, three churches, eleven streets, and a hill of Renaissance villas and gardens, were demolished.

Having excavated the imperial fora, Mussolini covered two-thirds of the remains under a thirty-metre wide coat of asphalt to create the Via dell’Impero (today known as the Via dei Fori Imperiali). The street connects the Colosseum—the monument that popular imagination most associates with imperial Rome—to Piazza Venezia, the administrative and ritual heart of Fascist Italy, where Mussolini had his headquarters. On this road, against the backdrop of imperial ruins, isolated from their surroundings and framed by empty space, spectacular processions of Fascist soldiers laboured the connection between Italy’s imperial heritage and its Fascist rulers.

Excavation of the fora has been debated for the last 15 years, with political ideologies often dictating archaeological proposals. Some advocated the total demolition of Mussolini’s Via dei Fori Imperiali, but in Dr La Rocca’s opinion this would have brought Rome’s traffic to a standstill and it was preferred instead to excavate the empty space framing the monuments to either side of Mussolini’s great road. Archaeological walkways will lead the public through the ruins and new museums will display discovered material.

The work is part of the mayor’s “Capital Rome” project launched in 1993 in run up to the Millennium. L19 billion (£6.9 million; $10.9 million) of the L30 billion (£10.8 million; $17.4 million) to be spent on the project were released in February.

The Ara Pacis: out goes Facism, in comes Richard Meier

If the necessary funds are made available, Millennium preparations will include new housing for the Ara Pacis Augustae. Richard Meier, the American architect whose work includes the Museum of Contemporary Art in Barcelona and who is also working on the new Getty complex, was asked to submit designs for a new structure to enclose the monument. The Ara Pacis—the altar of piece—is a marble altar dedicated in 9 BC by Augustus, to celebrate the peace following his victory at Actium in 31 BC. The walls are decorated in high relief with scenes illustrating the founding of Rome and the rise of the Julio-Claudian dynasty.

In 1938 a new technique that permitted freezing the soil of the marshy site was employed to recover all possible fragments and the monument was reassembled. It was enclosed in a larger structure made of concrete and glass on the outer walls of which Mussolini chose to inscribe the Res Gestae .

The Res Gestae—an autobiographical account of Augustus’s achievements as emperor, including detailed description of his building projects—was translated, exported and inscribed on temple walls throughout the Roman empire. For Mussolini it became the sacred precedent of Italian imperialism and justification for his dreams of a new Italian Empire. Pending the allocation of funds, the Fascist building is to be replaced by a new structure large enough to house a small museum.

• Originally appeared in The Art Newspaper with the headline "The archaeology of power"