The most recognisable landmarks of Milan include its medieval Duomo and futuristic skyscrapers, but now the city plans to turn a long-forgotten ancient site into a major attraction. At the new Parco Amphitheatrum Naturae (PAN), the ruins of a Roman amphitheatre will be filled with shrubbery, allowing visitors to imagine how the so-called Colosseum of Milan once appeared. Ongoing digs have already “rewritten chapters of Milan’s history”, the project’s organisers say.

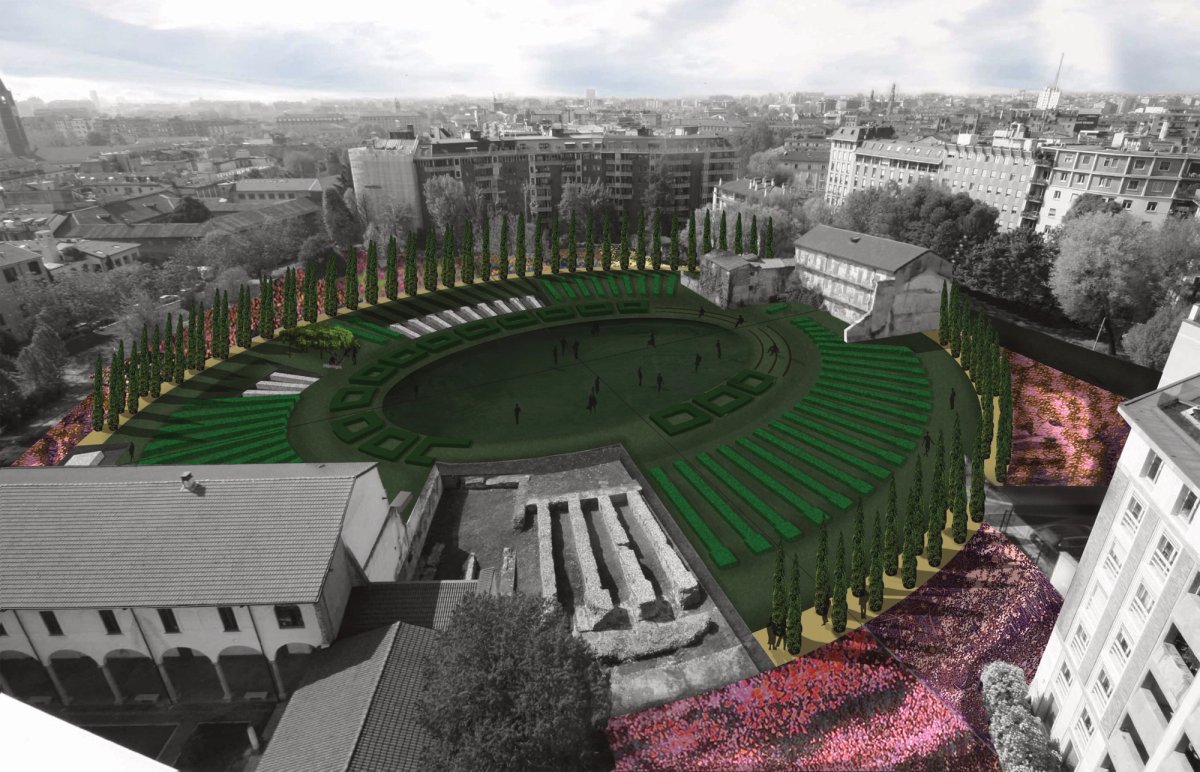

Hedges and trees will be planted, indicating where parts of the amphitheatre have disappeared Courtesy of the Superintendence of Archeology, Fine Arts and Landscape for the metropolitan city of Milan

Mediolanum, as the city was formerly called, was the capital of the Western Roman Empire from AD286 to AD402, when it boasted a palace, a circus, multiple basilicas, thermal baths and an enormous forum. Built during the first century, the elliptical amphitheatre originally measured 150m by 120m—slightly smaller than Rome’s Colosseum—but it was systematically dismantled at the end of the fourth century to provide material for new constructions, including the Basilica di San Lorenzo. Archaeologists located the site in 1931 and excavated seven foundation walls that supported the stands in the 1970s.

Some of the archaeological findings at the Roman amphitheatre in Milan Courtesy of the Superintendence of Archeology, Fine Arts and Landscape for the metropolitan city of Milan

In a new project launched in 2018, the city-owned archaeological park was expanded from 12,500 sq. m to 22,300 sq. m, making it Milan’s largest. Excavations coordinated by the state authorities began in 2019, leading to the discovery of 14 more foundation walls and a hypogeum consisting of two underground galleries from which gladiators and beasts were hoisted to the stage above. The €1.5m project is funded by Italy’s culture ministry and private donors, with PAN scheduled to open by the end of this year.

Recent discoveries include a marble head resembling Agrippina, the wife of the emperor Claudius Courtesy of the Superintendence of Archeology, Fine Arts and Landscape for the metropolitan city of Milan

Hedges of boxwood, myrtle and privet will mark out parts of the structure that have been lost, including the foundation walls, while more than 100 trees will form a passageway representing the amphitheatre’s outer walls. Wilder flower patches will counterbalance the “rational order” of the central Renaissance-style garden, says Attilio Stocchi, the project’s architect. The move was inspired by Giulia Caneva’s book Amphitheatrum Naturae (2004), which describes how artists and botanists flocked to Rome’s Colosseum between the 17th and 19th centuries to study the flora that had enveloped the site, he adds.

The council will devise a ticketing system that ensures PAN is accessible “on a daily basis”, says Pierfrancesco Maran, one of Milan’s deputy mayors. The park will become a highlight of an existing cultural route linking 18 ancient sites, including the Imperial Palace and Roman Circus, he predicts. Covering the hypogeum with a wooden stage will also allow the arena to be used for performances.

A birds-eye-view of the south east radial septa at the Roman amphitheatre in Milan Courtesy of the Superintendence of Archeology, Fine Arts and Landscape for the metropolitan city of Milan

Fragments from at least 150 pre-Roman vases dating from the fourth to third century BC were discovered at the park last year and suggest a Celtic sanctuary may have once been located nearby. This and other recent discoveries—including a spear and a marble head resembling Agrippina, the wife of the emperor Claudius—could be displayed in the Antiquarium museum located at the park’s entrance, or in an abandoned building that could be renovated using culture ministry funds.

The digs may continue even after PAN has opened, and the state authority hopes to consolidate its relationship with Milan’s Università Cattolicà, whose students conducted excavation work on the amphitheatre last August and September, says Antonella Ranaldi, Milan’s superintendent of archaeology, fine arts and landscape. Elsewhere, the excavation of the Basilica di San Dionigi in Porta Venezia, which was rediscovered in 2017, will resume shortly. “It is a good moment for archaeology in Milan,” Ranaldi says.