The art historian Alexander Alberro’s new book, Abstraction in Reverse, which has just been published by the University of Chicago Press, offers a fresh perspective on how Latin American artists have altered our perceptions of Modern art. The central argument of the book is that abstract artists like Julio Le Parc, Tomás Maldonado and Jesús Rafael Soto, among others, made works that granted viewers a fuller stake in interpretation, which was no longer a matter of passive reception.

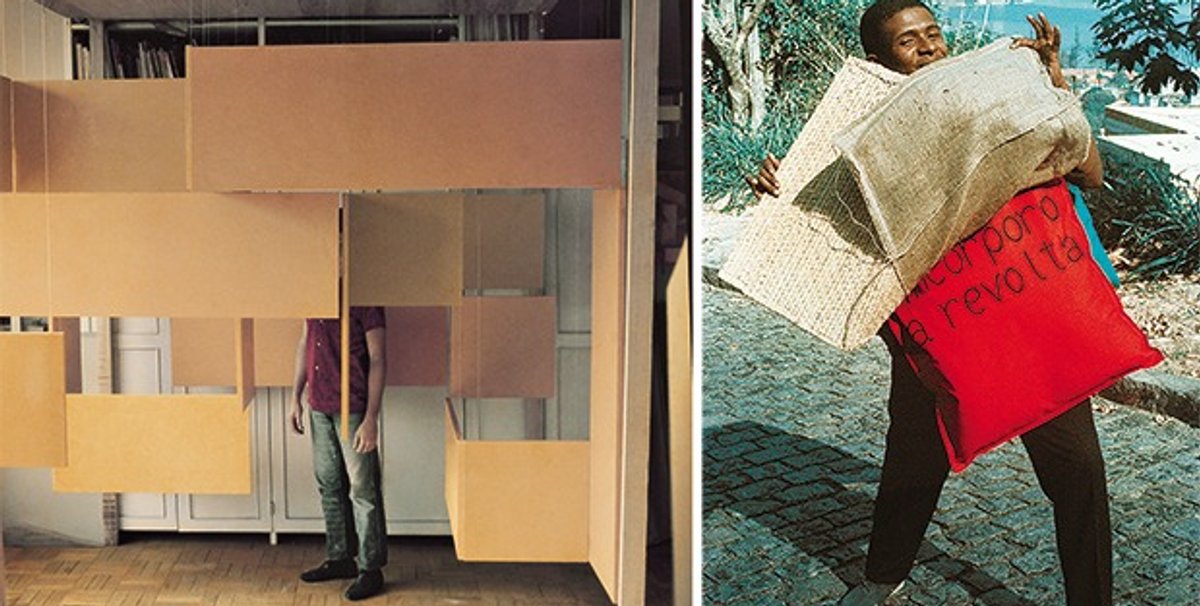

These artists "get rid of the 're-' in representation," Alberro says. "The dynamic of connection is between the spectator and the object, who now takes a greater role." Importantly, Alberro says, “the artwork was no longer made in advance and then exhibited; rather, it was produced at the very site where the art object and spectator meet, where object and subject come together.”

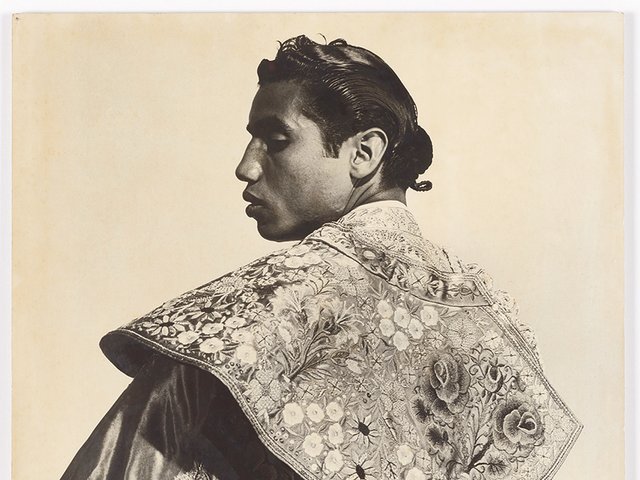

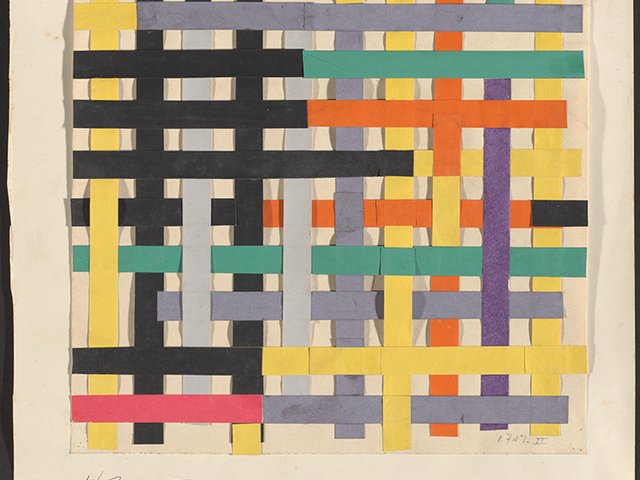

Latin American artists did not always have direct access to works by painters like Piet Mondrian and Kazimir Malevich, whom they admired. Often, works by artists like these were only available in black-and-white reproductions, which led to productive misreadings. In the first issue of the short-lived journal Arturo, which was founded in Buenos Aires in 1944, the artist Lidy Prati manually coloured in the reproductions of Mondrian's work. "When Soto finally saw a Mondrian, he realised he had it all wrong," Alberro says. "He thought Mondrian's work was completely smooth, with no visible brushstrokes and all straight lines meeting the edge of the canvas."

One of the keys to Alberro's book is that he takes a comparative approach to artists from various Latin American countries, which is a shift from the traditional narrative. "Artists like Le Parc in Argentina and Soto in Venezuela were dismissed or couldn't find a place in their national context," he says. "So Modernism, rather than an imposition, gave these artists the ability to speak and be heard in their own national contexts."

The below excerpt is taken from Alberro's introduction to the book.

During the mid-20th century, Latin American artists working in several different cities altered the nature of Modern art in ways that have never been fully appreciated. In this critical transformation, art’s relation to its public was reimagined, and the spectator was granted a more significant role than ever before in the realization of the artwork. These developments unfolded in the context of a complicated mediation of the particular form of abstract art that European Modernist artists Theo van Doesburg, Max Bill, and others referred to as Concrete art. This type of abstraction resonated in Latin America not only as a result of European Modernism’s hegemony but also because it articulated an experience of Modernity that, despite all cultural differentiation, was becoming increasingly global. Initially, in the 1940s, Latin American artists with Modernist ambitions faithfully adopted Concretism, following their European predecessors in banishing all categories of description and imitation in favor of an emphasis on the sheer inventiveness of a simple operation generated entirely from the mind of the artist and communicated lucidly to the spectator. The task of the spectator in turn was to avoid any particularities that might obstruct her deindividualized gaze and to subordinate herself entirely and without interference to the logic of the art object, enabling the artwork’s import, its meaning, to be comprehended fully. Vision was the primary means for this model of spectatorship, and any phenomenological aspect of the experience was to be avoided.

But Latin American artists would soon push Concrete art considerably beyond its established boundaries. Indeed, most of the artists whose work is central to Abstraction in Reverse created their distinctive identity by rejecting the a priori generalizations of pictorial or sculptural Concretism and offering an alternative to it. In their effort to imagine art as an integral aspect of an intellectual life that responded to their own particular concerns, they put aside the Concretist notion that the meaning of an artwork is established prior to its experience by the spectator in favor of a concept of artistic signification (as much as of consciousness and subjectivity) that assumes that meaning can be produced only in the site where the art object and spectator meet, where subject and object come together. I call the site of this intersection the “aesthetic field” of the artwork, defining it first and foremost as an area of possibility through which the spectator constructs meaning, and I focus this study on the structuring of artistic signification according to the interrelationship of subject and object within this aesthetic field. Consistent with their negation of idealist aesthetics, Latin American post-Concrete artists interwove the specificities of the material object and the context of its exhibition and display with the spectator’s subjective experience within the aesthetic field in ways that thread the work of art back into the fabric of the world.

By reshaping the aesthetic field to posit the spectator not as a disembodied receptor of optical stimuli but as an active subject engaged in a new kind of attentiveness and tactile encounter, post-Concrete artists opened the way for new modes of consciousness and experience, as well as new models of subject-object relations. My thesis, in brief, is that in breaking in various ways with the core dictums of Concrete art, Latin American artists in the mid-twentieth century reimagined the relationship of art to its public and produced artworks to challenge prevailing notions of the interconnection between subject and world, perceiver and perceived, objective reality and subjective experience. In this new con-ceptualization, art was no longer considered entirely autonomous and internally coherent but relationally dynamic, prompting the imaginative engagement of the spectator and producing meaning through this very relationality. The rationales underlying the generation of this art varied, as did the degrees and conditions of subjective agency it actualized, but the new post-Concrete art in Latin America fundamentally reconfigured the aesthetic field and Modernist spectatorship more generally, and the particular forms these new modes of sensibility took are the primary concern of this book.

Along with a realignment of the aesthetic field and the development of new conventions of spectatorship, ambitious mid-20th-century Latin American art manifested a new type of artistic subjectivity. For reasons that are as much political and cultural as they are aesthetic, these artists discarded the traditional, artisan-like exercise of manufacturing the artwork in favor of presenting catalytic objects or ensembles that encompass, and in fact require, the spectator for their completion. If, as noted a moment ago, Concrete art’s form of spectatorship closed the art object in upon itself, conveying an idea or act carried out by the artist at an earlier moment, then the importance of the new post-Concrete work lies in the context of spectatorship. Henceforth the artist performs “no longer as a creator for contemplation, but as an instigator for creation,” as Brazilian artist Hélio Oiticica put it. In this new condition, the function of the artist is limited to the presentation of formal elements or situations to be constructed into artworks in the context of the aesthetic field. This process of configuration and the link between forms of artistic signification and forms of spectatorship are central theoretical concerns of this book. My argument is that meaning does not reside in the intent of the artist, nor in the essence of the art object, nor in its site of display, nor even in the consciousness of the spectator engaging with the work. Meaning is constructed in the aesthetic field, a space that includes all of these elements as well as writings and statements made by the artists and others about the work. In this respect, the aesthetic field differs from the logic of what philosopher Jacques Rancière refers to as an emancipatory practice of art in which the centered subject is fully capable of seizing hold of aesthetic experiences, and constitutes instead something similar to what philosopher Michel Foucault describes as an “apparatus” of a “system of relations” that is established among a set of components. My goal in what follows is to study what Foucault called the “interplay of shifts of position and modifications of function” among the elements that structure the work of mid-20th-century Latin American artists, keeping in mind that with each shift or modification the hierarchy of these constituent parts is readjusted or reworked. Moreover, insofar as the aesthetic field as an apparatus is always inscribed in what Foucault refers to as a “play of power,” it will be important to comprehend some of the reasons that led to this reconfiguration in the mid-20th century.

Then, too, the aesthetic field as an apparatus implies “a process of sub-jectification”; that is to say, it produces its subject, it orients the gestures, behaviors, opinions, or discourses of living beings into subject positions. This is what separates it from sociologist Pierre Bourdieu’s framework of a “field” of cultural production. Although both concepts theorize a field as hierarchical, the goal of Bourdieu’s analysis is to understand the ways in which the subjects and institutions that specialize in creating, displaying, distributing, and evaluating art interact, and in particular how the fully formed subject negotiates the social and economic context of art at a given time and in a particular place. The ensemble of relations that structure the aesthetic field that I propose includes the context singled out by Bourdieu. But I understand the spectatorial subject as a position that is itself formed in the aesthetic field. This approach requires paying greater attention than does Bourdieu to the way the dynamic system of relations established among the elements of the aesthetic field are configured, as well as to the spectator’s interaction with the formal or material techniques that actually make art.

The turn to action and participation in the context of spectatorship in Latin American art also marks a shift to an entirely different mode of social engagement of the artwork. The model of spectatorship that develops as artists attempt to reintegrate art into the social realm by asserting its relationship with the viewing subject turns outward into the third and fourth dimensions. This, in essence, is at the core of what I refer to as “abstraction in reverse.” To quote a 1960 text by Ferreira Gullar, a Brazilian critic whose early writings are important to my investigation, post-Concrete artists, in their “attempt to reconnect the picture plane with painting’s need for spatialization,” invert traditional perspective and create “an outward three-dimensional virtual space” powerful enough “to break away from (even abstract) representation.” The gap between the ostensible permanence of the art object and the ephemerality of the spectator’s interaction with it accordingly narrows and in some cases collapses altogether. The artwork ceases to be a stationary object accessible to immediate and exhaustive viewing (that is, seen in its entirety) and invites an embodied reception located in space and time. The artistic experience becomes a transitional phenomenon, prompting the spectator to relate with others and with an environment that surrounds and envelops her. But rather than rest in the moment of desublimation, the spectator is induced by some of the artworks produced in this manner to see herself both as an integral subject and as an object of the perception of others, creating new, liberating spaces of sociability. Gone is the myth of the singular artist in absolute control of her creative production. Gone too is the traditional understanding of the ontology of art in which the artwork and its conceptualized essence stand apart from the world and unchanging for all time. In place of these singularities, these artworks posit a relational identity and set of processual operations that are not atavistic but disjointed, having multiple roots, facets, and directions. The subjective agency and creativity of the spectator become paramount in the realization of the artwork.

Alexander Alberro is the Virginia Bloedel Wright Professor of Art History and Department Chair at Barnard College