The tradition of hard-edge geometric abstraction as it was practised in Latin America has always presented something of a conundrum for global art history. Opinion sways between those who identify in its history some of the most innovative developments of the 20th century, and those who accuse it of being an outdated, Eurocentric and developmentalist project of the elite, silencing other, more ‘authentic’ voices.

Positing abstraction as an apolitical formalism versus a politically engaged figuration is an old dialectic that has played out globally since the early decades of the last century. For this reason Radical Form: Modernist Abstraction in South America is especially well timed, as Megan Sullivan, an assistant professor of art history at the University of Chicago, does a remarkable job of forgoing this zero-sum debate, bringing the complexities and contradictions of artistic practice and cultural context into a richer and more nuanced dialogue.

Sullivan concentrates exclusively on the work of four artists from the South American continent spanning the first six decades of the 20th century: Joaquín Torres-García (Uruguay), Tomás Maldonado (Argentina), Alejandro Otero (Venezuela) and Lygia Clark (Brazil). At least two of these artists are nowadays better known—Torres-García and Clark have each been the subject of retrospective exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, in 2015-16 and 2014 respectively—but even in those cases, Sullivan introduces new perspectives and readings to their work.

Sullivan defines her approach as “microscopic rather than telescopic”, making a case for close examination of the artists’ works, intentions and contexts. Her in-depth analysis allows us to better understand the complexities of artists who “overtly aligned themselves with the tenets of the European historical avant-garde” without apologies. What we learn from this approach is that all intentions—even those that are overtly cosmopolitan—are inevitably conditioned by time and place.

Rejecting rationality

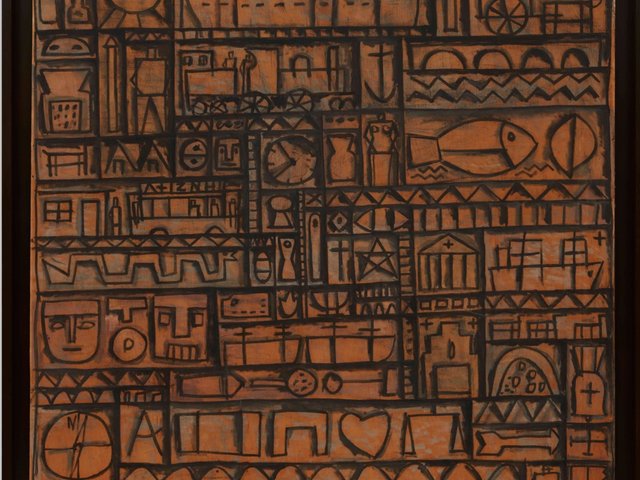

Torres-García (1874-1949) is often considered the father of abstraction in Latin America. A first-generation Modernist, he worked alongside the noucentistas (a form of Catalan Art Nouveau/Symbolism) in Barcelona, and then with Mondrian and Michel Seuphor in Paris, but came to reject European abstraction as too rational and reductive. In its place, he developed an elaborate theory of ‘constructive universalism’ as an amalgam of the art of all cultures, with a special interest in the ancient Americas.

Sullivan homes in on what she calls his “highly aestheticized telluric fantasy”, made without any real knowledge of pre-contact cultures beyond what he saw in the museums of Paris. In this sense, his “call for rootedness … largely devoid of roots” points to the risks of simply identifying any Latin American as an ambassador for ‘authentic’ culture by virtue of their nationality. Sullivan’s analysis of the roots of this thinking is insightful, while also recognising that the ongoing fantasy of otherness was an essential and motivating part of the Modernist project.

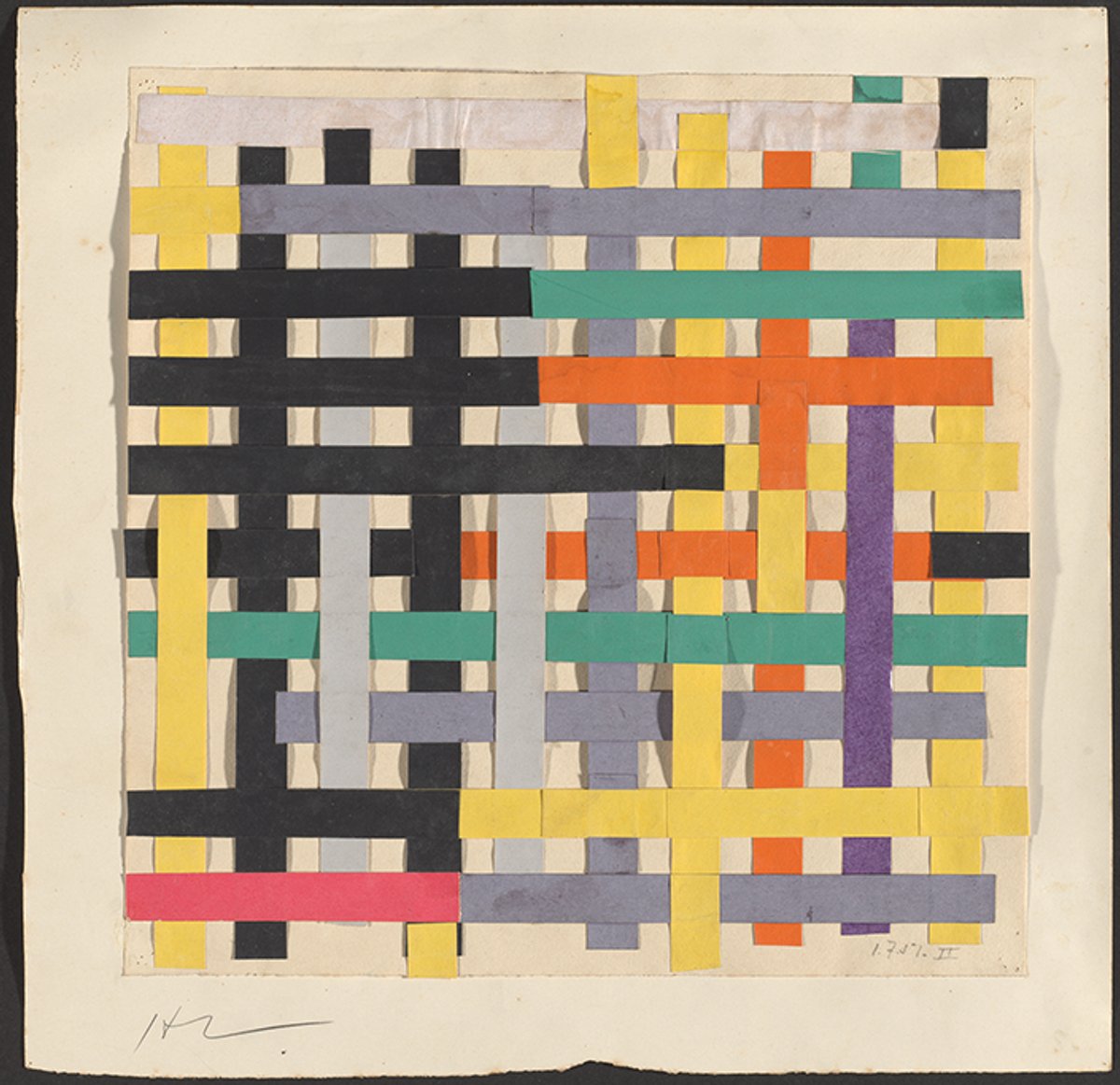

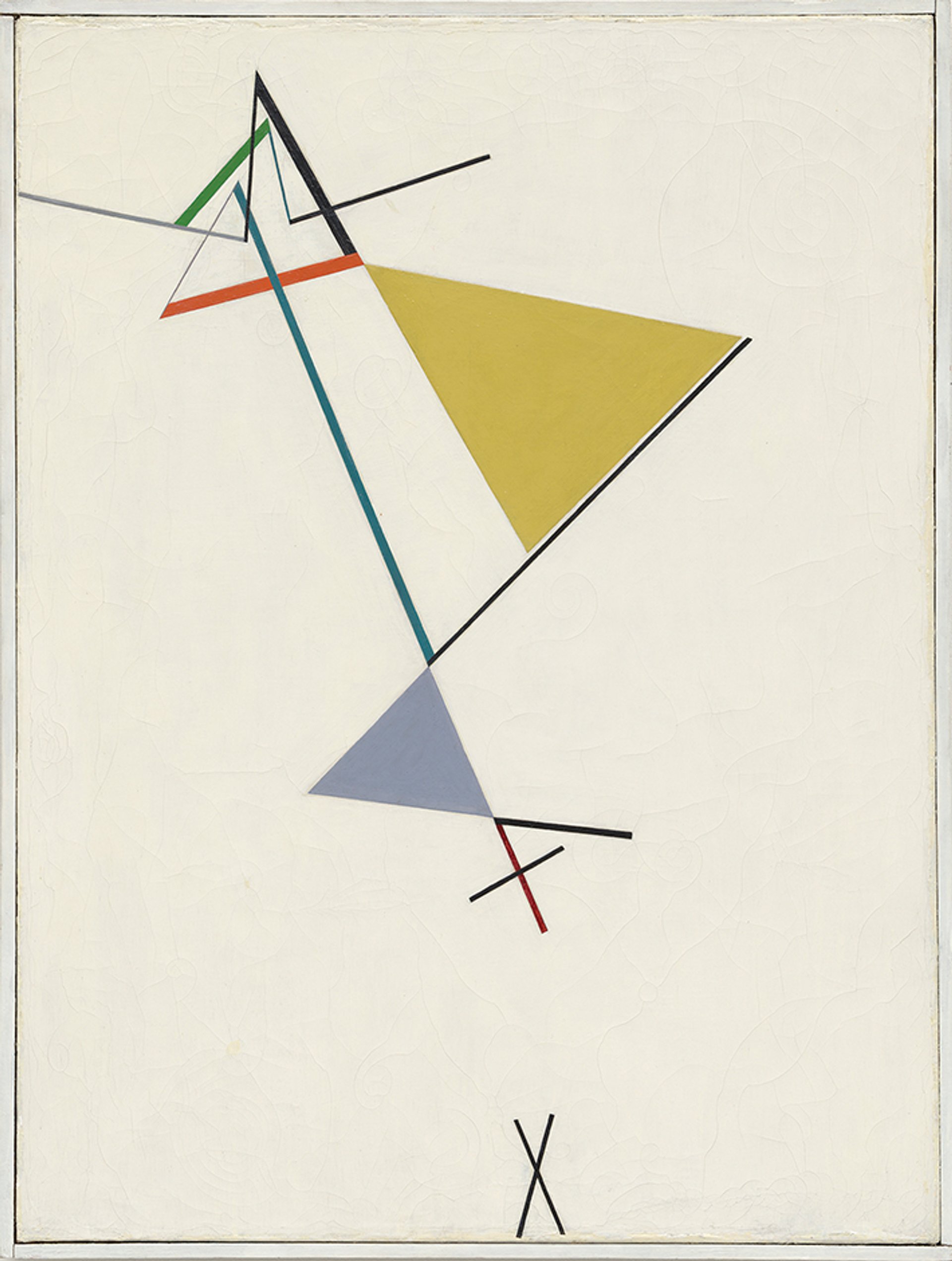

Tomás Maldonado thought that universalism could only be achieved through hard-edged abstraction, as in his Development of a Triangle (1949) © Tomás Maldonado. Image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY

Maldonado, a much younger artist born in Buenos Aires in 1922 (he died in 2018), famously made similar critiques of Torres-García, but in this case from a more conventionally Modernist perspective. For Maldonado and the artists who coalesced around him in the mid 1940s, Torres-García was a traitor to the hard-edge and rationalist language that they, perhaps simplistically, associated with Mondrian and the Bauhaus. For Maldonado, universalism was also the goal, but could only be achieved by the ‘scientific’ means of hard-edge abstraction.

Sullivan observes that Maldonado’s “relative indifference to the pathologies of modern reason”, together with his embrace of Soviet Marxism (the early journals of the group included texts by Stalin and Lenin), led to his quixotic attempt to convince the Argentine Communist Party that abstraction was indeed the language of revolution and that they should return to the Russian Constructivist spirit of 1917. Sullivan digs deep into Maldonado’s communism, and brilliantly identifies Engels, not Marx, as the leading philosopher of this movement.

Abstraction and aspiration

While Torres-García and Maldonado were both to some extent marginal figures in their contexts, the case of Otero (1921-90) in Venezuela is quite different, thanks to the rapid expansion of the oil industry in the 1950s, and the adoption of abstraction as the unofficial visual language of a modern aspirational state. Sullivan accuses Otero—and by extension the Kinetic artists who worked alongside him on huge state-sponsored projects—of practising “a modernity that lacked a modern foundation”. In her analysis, Otero’s work posited an escapist, deeply personal experience of colour and form that privileged “individual experience and agency”.

The same could be said of Clark (1920-88), the final artist discussed in this book, and it is true that, like Otero, she emphasised the individual over the social. It’s also no coincidence that both Brazil and Venezuela were countries that grew rapidly after the Second World War, and embraced the languages of abstraction and Modernism in architecture, design, public works and art. In this context of state-supported art, the interior and subjective space takes on its own radical potential in contrast with the overriding logic of developmentalist capitalism.

Sullivan describes her book as “a chronicle of failure”, which, while true in one sense, seems perhaps a little harsh. It is true that none of the artists she discusses came anywhere close to realising their visions of utopia, but that is a charge that can ultimately be levelled at every Modernist artist, regardless of their context. However, Sullivan’s close reading, contextual sensitivity and sidestepping of grand simplifying narratives make this book an extremely valuable addition to the growing literature on art from regions outside the classic mainstream.

• Megan A. Sullivan, Radical Form: Modernist Abstraction in South America, Yale, 232pp, £50/$65 (hb)

• Gabriel Pérez-Barreiro is an art historian and curator, and senior adviser to the Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros (Caracas and New York City)