Alfredo Boulton (1908-1995) was a dapper and sophisticated Caracas-born Venezuelan from a wealthy merchant family who, like many Latin American intellectuals of the period, dedicated himself to numerous activities: photography, art history, politics, cultural diplomacy and collecting, as well as multiple business enterprises. The range of these interests makes it hard to pin him down, but they also allow us to detect a broader sense of cultural purpose that cuts across all these disciplines.

As Mary Miller, the director of the Getty Research Institute, states in her introduction to this remarkable book, Alfredo Boulton: Looking at Venezuela 1929–1978: “In no small measure, Alfredo Boulton is the essence of 20th-century Venezuela, a mantle I suspect he would gladly accept.” Boulton has become such a paradigm for a certain vision of modern Venezuela that it is almost impossible to separate him from a national identity that he both reflected and, in many ways, constructed. Boulton’s Venezuela was a country in rapid expansion due to the discovery of massive oil deposits and a national government that was democratic and developmentalist. Perhaps more than any other country in Latin America, Venezuela embodied the values of the American Dream, yet its cultural identity, thanks in part to Boulton and his intellectual cohort—including the critic Mariano Picón Salas and the political theorist Arturo Uslar Pietri—tried quite explicitly to forge a national identity that was rooted in its specific history.

Mestizaje essence

For Boulton, the essence of Venezuela was in its mestizaje, a mixture of white, Indigenous and Black cultures. He was the first person to document art and artefacts from the Pre-Hispanic, Colonial, 19th-century and Modern periods of Venezuela, publishing scholarly accounts such as his three-volume Historia de la pintura en Venezuela (1964-1972) that emphasised continuity over rupture, as if all these artistic forms were roots feeding into the trunk of Venezuelan identity. In Boulton’s art-historical model, all traditions converge in Modernism, where they fuse into a harmonious whole.

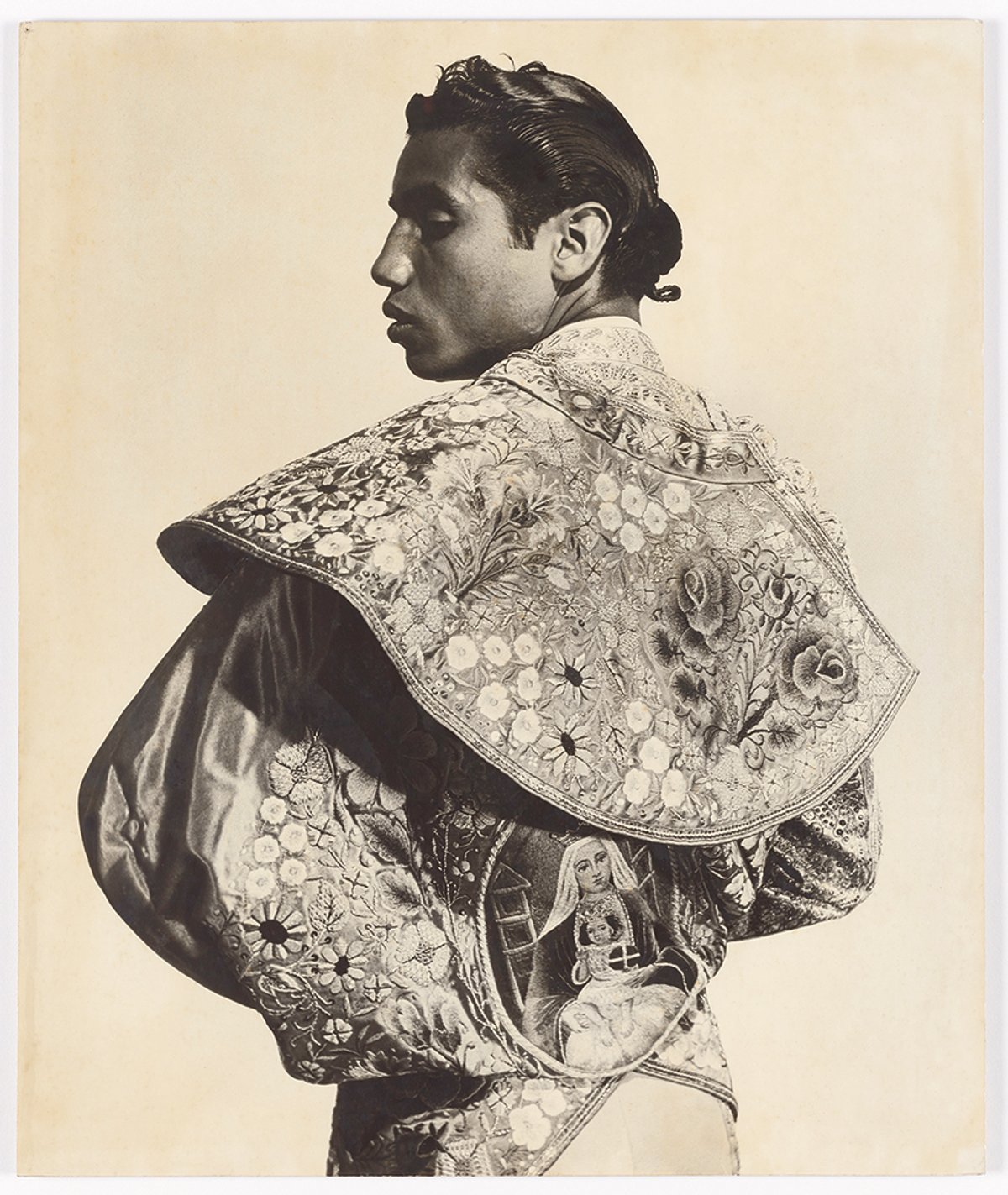

His exotic and sexualised representation of mestizo men represent his intellectual construct of a successfully fused multi-ethnic culture

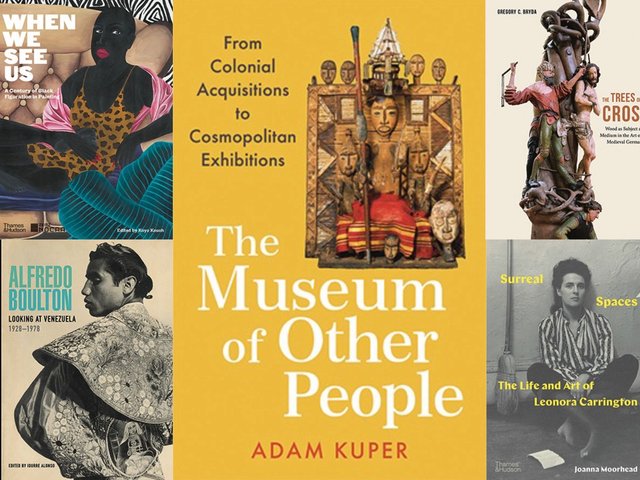

Although Idurre Alonso, the book’s editor and Getty Research Institute’s curator of Latin American collections, makes the claim that “there has never been a project that looks at Boulton from a multidimensional point of view and emphasises his influence in the shaping of art”, this is not strictly true. In 2008 the Museum of Modern Art in New York (MoMA) published an almost 400-page volume, Alfredo Boulton and his Contemporaries: Critical Dialogues in Venezuelan Art 1912–1974, which was subsequently published in Spanish by Fundación Cisneros in collaboration with MoMA. The MoMA volume contains several of Boulton’s own writings, which are absent from the Getty book, but covers many of the same issues.

This new volume is published to mark the acquisition by the Getty of Boulton’s archive, including his photographs and papers, and accompanies an exhibition at the Getty Center (29 August-7 January 2024). The Getty brought together an international group of scholars to analyse the material and publish their findings. While the Covid-19 pandemic interrupted the full process, the result is nonetheless very impressive, with especially insightful essays by Alonso, Natalia Majluf, Jorge Francisco Rivas Pérez, Mónica Dominguez Torres and Alessandra Caputo Jaffe, each of which focuses on a different facet of Boulton’s life and work. The book is structured in three sections, each looking at a specific aspect of his career: his photography, his relationship to Modern art, and Boulton the art historian.

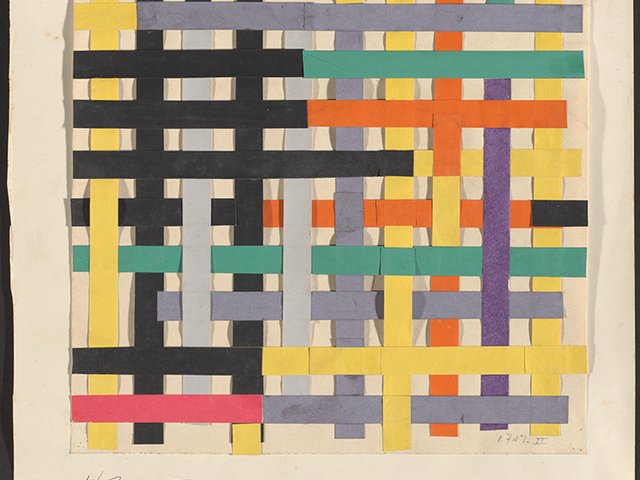

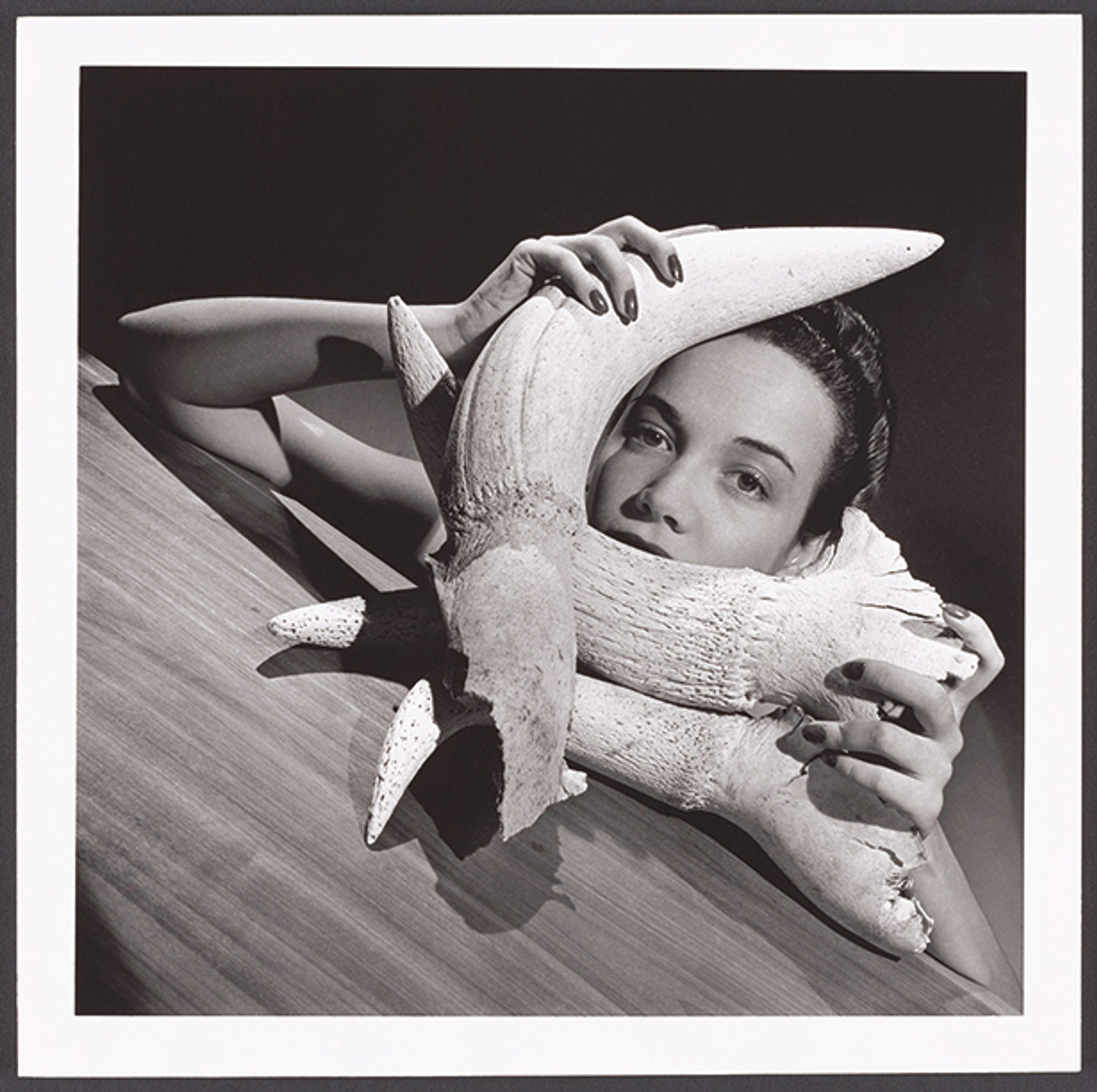

Flora; la Belle Romaine (around 1940)—Boulton was influenced by both Surrealism and Constructivism

© J. Paul Getty Trust, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles

As a photographer—he was given his first camera in 1920 by his uncle, Henry Lord Boulton, and studied in Europe, influenced by contemporary Surrealism and Constructivism—Boulton was not quite in the league of other artists of the period, such as Alfred Stieglitz or August Sander, and his attempts to have an international career mostly floundered. But, as this book argues, his images nonetheless provide a fascinating window into contemporary Venezuela—and, especially, his relationship to it. His exotic and sexualised representation of mestizo men represent both his intellectual construct of a successfully fused multi-ethnic culture and his own thinly veiled attraction to these same bodies. Alonso rightly points to the problematic nature of this projection from a member of a mostly white elite, while also providing an interesting conceptual framework in which to understand the images and their context of “belleza criolla” (creole beauty).

Tireless promoter

In his relationship with Modern art, we see Boulton as a tireless promoter of Venezuelan art, using and building networks with institutions like MoMA (of which he was the International Council chairman) and the Organization of American States in Washington, DC, to promote Venezuelan artists. Unfortunately, the period in which he was most active, the 1960s and 1970s, were barren in terms of international interest in Latin American art. Beyond the scope of this book, it might have been interesting to see how some of those seeds bore fruit after 2000, with exhibitions like Armando Reverón at MoMA in 2007 or the current Gego exhibition (Gego: Measuring Infinity until 10 September) at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. Venezuelan Modernism became very much part of the art-historical canon, a process Boulton did not get to experience directly, but which can be attributed, in part, to his efforts to make the country’s art legible abroad.

The section dedicated to Boulton’s art history is illuminating, as it focuses on his extraordinary archival efforts to trace the production of Venezuelan Colonial artists when few people considered them to be of any interest. In the dominant narrative of the time, Peru and Mexico were the centres of Colonial production, and Boulton made a compelling case for the inclusion of the Caribbean as an important centre for production and exchange of artistic languages between the Catholic and the native. Equally remarkable is his obsession with the figure of Simón Bolívar (1783-1830), the liberator of Venezuela from the Spanish Empire. Boulton organised an exhibition in which he traced the physiognomy of Bolívar through his representation in art, seeing how his features vacillated between white European, Black and mestizo, depending on the political winds of the times.

In 2010, Hugo Chávez, the then president of Venezuela, ordered the exhumation of Bolívar’s remains, to be performed live on national television in one of the most extravagant and disturbing spectacles of modern politics in this century. His purpose was to prove that Bolívar had been poisoned by the Spanish, and he described looking into Bolívar’s skull and communicating with him beyond the grave. Herein lies one of the tragedies of contemporary Venezuela: how the refined scholarship of someone like Boulton inadvertently created an image of the country embodied in its historical liberator, an image ready to be literally manipulated in the pursuit of a populist and catastrophic political programme.

Alfredo Boulton: Looking at Venezuela 1929–1978 paints a compelling portrait of a period in which art, art history and politics were part of a modernising project—a project that then fell apart in multiple ways. This publication has the merit of resisting the temptation to tell this tragic story of subsequent national collapse, focusing instead on trying to understand Boulton in his original context.

• Idurre Alonso (ed), Alfredo Boulton: Looking at Venezuela 1929–1978. Getty Publications, 288pp, 164 colour & 19 b/w illustrations, $60/£50 (hb), published 18 July