One does not have to look far these days to find monsters. They walk among us, unmasked, armed, and shooting off their mouths. Then there are the demons within, even more numerous. Less in evidence are the sort of cartoons that can give these stubborn beasts a proper skewering.

Like everything else in life, it used to be different. Every newspaper had a syndicated political cartoonist. Every era had its scourge. Where are our Daumiers, our Thomas Nasts, our Hogarths? Our Charlie Hebdos, for that matter? Is real life in the Covid era too dark even for caricature?

But why worry about the absence of tempering malice on the printed page when we can reacquaint with the hand of the master, Francisco de Goya, in a show of drawings and prints that feels both urgent and timely. If the terrorists, libertines and grotesques he depicted are more than two centuries old, human behaviour hasn’t changed, and that is what Goya’s pen and brush reveal in each of the 100 examples on view.

With the Capitol insurrection so recent in our experience, there can’t be a better time to reckon with Goya than nowLinda Yablonsky, art critic

Goya’s experience as a court painter may have elevated his social status, but it must also have given him a very dim view of humanity as a whole. In some works, motherhood expresses itself with the cruelty of public executioners, while society’s hopelessly deformed wretches have a certain appeal. They are also among Goya’s most enduring figures. That doesn’t mean his turn to fantasy and witchcraft is any less captivating. If anything, the winged devils and hot pockets of romance are most erotic. And crazy.

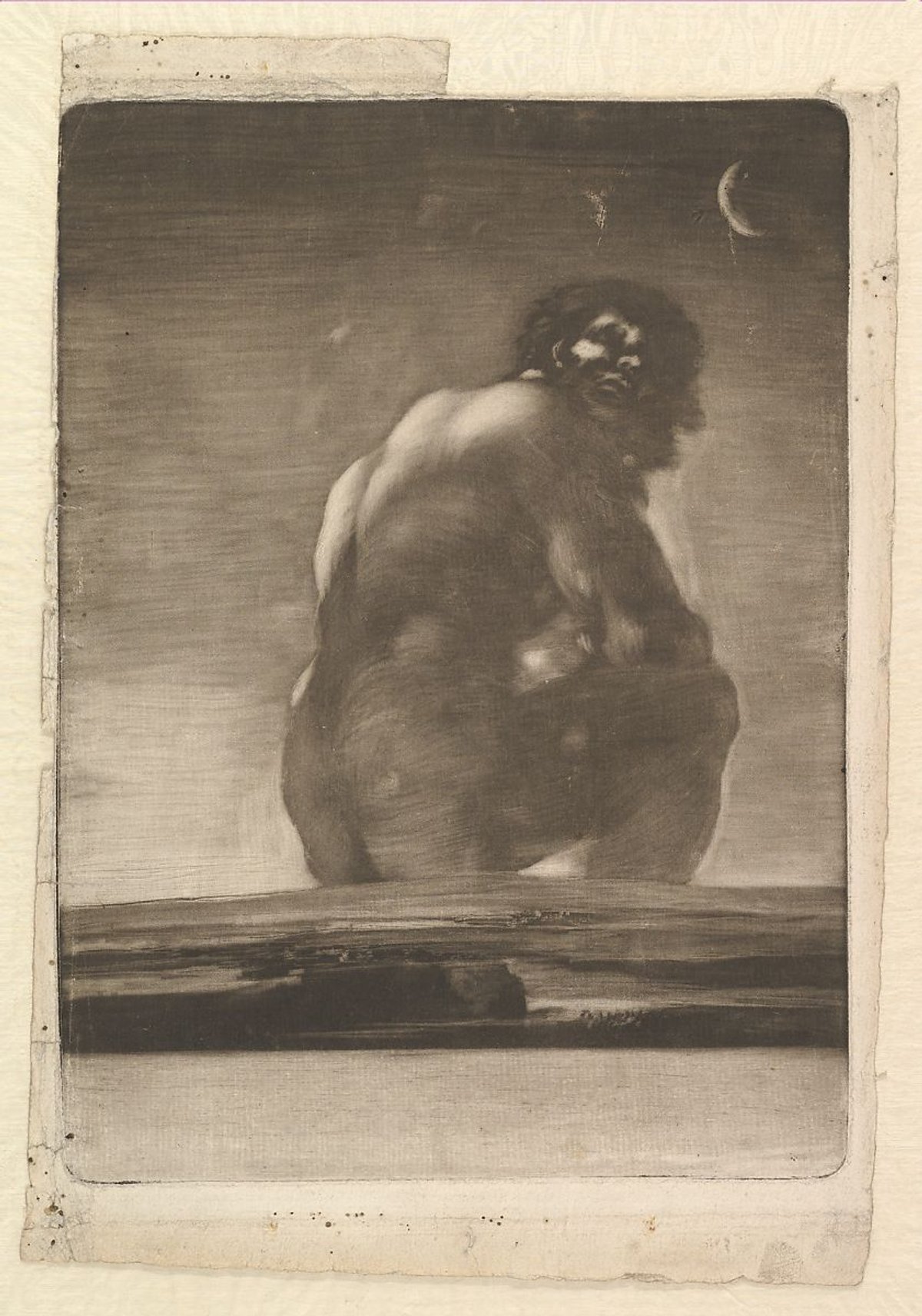

Preparatory study for The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters (1797)

Going deaf seems to have driven Goya to the intimacy of paper to vent his outrage and frustrations. The majority of works here come from the Met’s own collection, including the bullfights that Goya observed, late in life, during his voluntary exile in France, and the albums chronicling the domestic foibles and night terrors of life during the Inquisition. The rest are selections from the Disasters of War and Los Caprichos portfolios, their imagery so indelible that they continue to haunt the collective memory.

Still, it’s one thing to have studied a familiar image such as The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters, and another to see its two preparatory drawings hanging side by side. The earliest, on loan from the Prado, has an otherworldly glow that caught my eye even from across a crowded room; on closer inspection, it was fascinating in every detail.

To that end, no one moves through this show quickly. And there lies the main distraction of this presentation. The drawings are quite small, as are the galleries containing them. Even with reduced capacity and mask protocols in place, other bodies get in the way. People in the galleries on the day I saw the show were respectful of one another, but their proximity was so unsettling that it was hard to concentrate, and concentrate one must, in the necessarily dimmed lighting, to discern the nuances of each work. That is where the pleasure of seeing them lies and what the printed catalogue cannot capture on its own. Ultimately, for all of Goya’s pointed commentary, there isn’t a single line or shadow that isn’t fraught with tangible beauty.

Due to light sensitivity, the drawings can’t come up for air all that often. And with the Capitol insurrection so recent in our experience, there can’t be a better time to reckon with Goya than now.

• Goya's graphic imagination, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Until 2 May

• Curator—Mark MacDonald, department of drawings and prints, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Disasters of War (1815)

Our pick of the prints

On our The Week in Art podcast Francisco Chaparro, a contributor to the Met’s catalogue, discussed one of Goya’s most terrifying images.

“This is one of the greatest moments in the history of Western art—and Goya repeats the strategy in another plate in The Disasters of War series. One can’t look is a choreography of emotions, of people’s suffering. Each individual is carefully represented—how he or she is reacting to the fear of the moments before they die. And then you see this impersonal, headless machine of war: the row of bayonets. It seems to be like a slice of reality: time has frozen, but also the space is cut in half. An arrow-shaped space at the right of the composition, made with a direct wash of acid, points at the figures, so we know there’s something coming from the right side, a very violent event, and the impact is going to be felt in a few seconds.”

• Listen to The Week in Art on the usual podcast platforms