Goya: the Witches and Old Women Album, which accompanies the exhibition of the same title at the Courtauld Gallery in London (until 25 May), ilustrates, describes and analyses the loans from a dozen European and American collections that reunite, for the first time, all 22 of the surviving brush and black-ink wash drawings thought to have once made up Francisco Goya’s Witches and Old Women Album. These are presented alongside 29 comparative examples of the artist’s work on paper. This album was the smallest of the eight such compilations Goya created between the mid-1790s and 1828 (the last three decades of his long and illustrious career), and was disassembled and dispersed after his death. Informed by more than a century of intermittent scholarly concern with Goya’s album drawings, the show and its meticulously enlightening catalogue aim to inaugurate a new phase of art-historical enquiry.

Chiefly responsible for the Courtauld project is Juliet Wilson-Bareau, the co-author of the 1971 Goya catalogue raisonné and the organiser, in 2001, of the first show devoted to selections from the albums. In preparation for the 2015 venture, she led an unprecedentedly thorough collaborative investigation focused on establishing the order in which Goya had intended his captioned drawings to be “read”, so as to tease out an overall narrative logic. Remarkable in itself, this approach is now proposed as a model for study of the remaining albums.

In dating the Witches and Old Women Album as late as around 1819-23, Wilson-Bareau locates these drawings in a time when Goya was himself definitively an old man (he had turned 70 in 1816) and might be assumed to have shed all fond illusions about humanity—as is indeed suggested by the almost exactly contemporary Black Paintings. But the 22 album sheets range wider, in both theme and mood, than their conventional collective title would suggest.

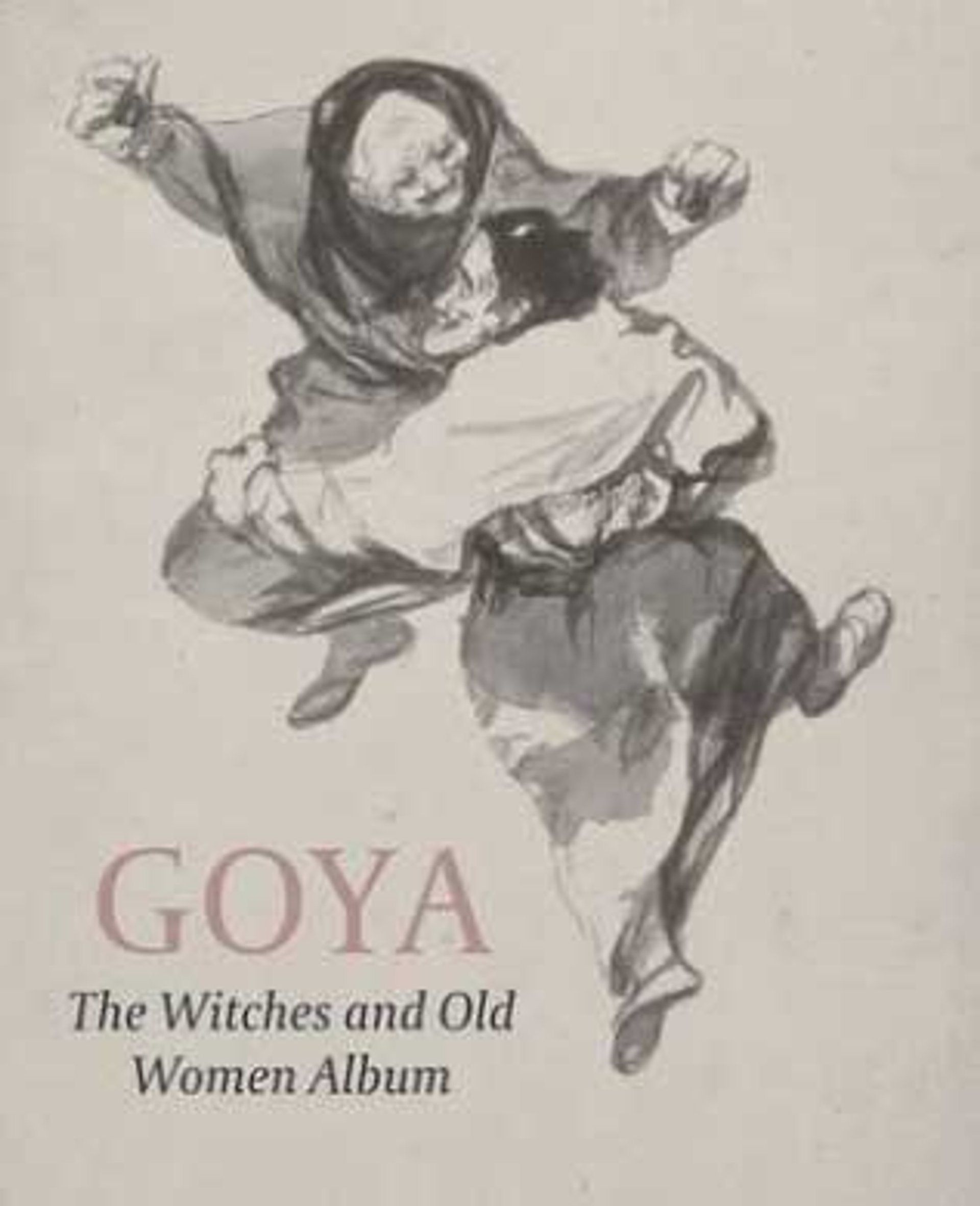

Devotees of witchcraft alternate with oppressed mortals, characters from Spanish literature with figures of Goya’s own invention. And the frailties, indignities and delusions of old age are shared by men and women. A lunatic’s harangue, the avarice of a “covetous old hag”, or the wide-eyed terror of the plummeting, androgynous figure seen in Nightmare are set against the unabashed lust of an airborne couple representing Mirth.

Goya: the Witches and Old Women Album

Juliet Wilson-Bareau and Stefanie Buck, eds

The Courtauld Gallery in association with Paul Holberton Publishing, 200pp, £30 (pb)

Elizabeth Clegg is an independent scholar who writes chiefly on 19th- and 20th-century art in Slavic and Germanic Europe. She has a particular interest in the Austro-Hungarian Empire and its successor states, and is the author of the 2006 Pelican History of Art volume on Central Europe 1890-1920.