When Nicole Fleetwood, a professor of American Studies and Art History at Rutgers University, began delving into the art that the US prison makes, over a decade ago, most people looked the other way. Whether applying for funding or proposing public programmes on the subject, she met with a wall of indifference, from blanket “no”s to the kind of reactionary response—“Why would you glorify criminals?”—that belies at best wilful ignorance. But hers, as she puts it, is a radical practice. And the fruits of her persistence take shape this month in a landmark group show with which MoMA PS1 in New York inaugurates its post-lockdown programming.

Marking Time: Art in the Era of Mass Incarceration features more than 35 artists in a collective reckoning with the havoc US punitive justice wreaks on every level: individual, familial, societal. Mass incarceration, as the New Yorker critic Adam Gopnik wrote in 2012, is the fundamental fact of contemporary America. With more than 2 million people in incarceration, it rivals countries in terms of population; and college in terms of prevalence as the defining event for much of the nation’s young and poor. It shapes cultures, drives economies. Mostly, it destroys communities.

“This is an intervention”Nicole Fleetwood, curator

To everyone involved in the show, though, this is not something they have read about in the New Yorker: they are from the communities being destroyed. Fleetwood hails from a part of south-west Ohio that she describes as hyper-incarcerated. She first began to notice what was on the walls while visiting relatives in prison. Each of the artists’ own experiences echoes one side or the other of that same equation: either they have experience of incarceration themselves, or it has directly impacted their lives. And that is what sets this show apart.

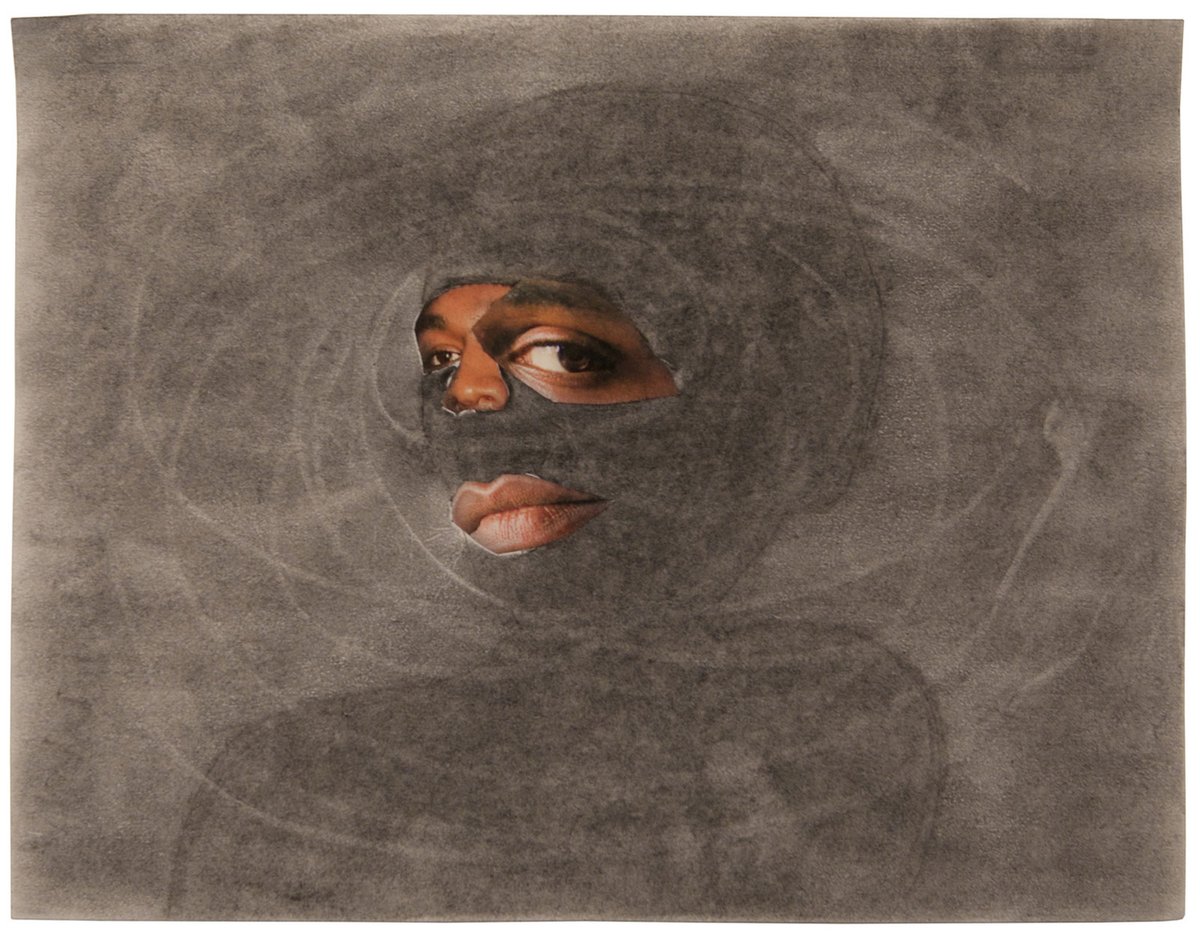

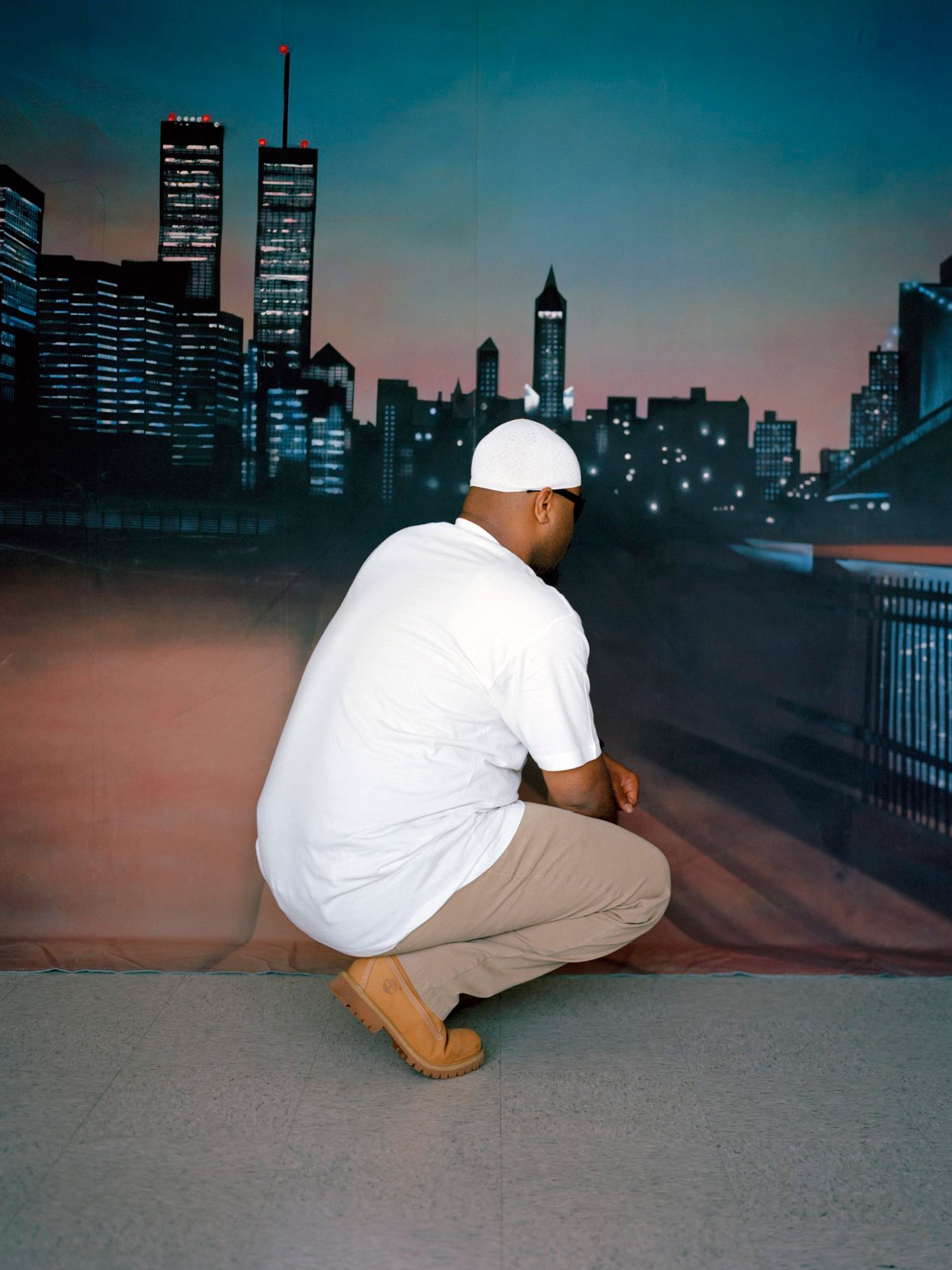

Larry Cook's The Visiting Room #4 (2019) Courtesy of the artist

Previous exhibitions have tended to focus either on incarceration as a theme, like Andrea Fraser’s installation of audio recordings from a correctional facility at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 2016, or on the art made by imprisoned people, such as the Drawing Center’s recent group show The Pencil is a Key. The latter are usually described as outsider artists. This, to Fleetwood’s mind, only serves to embed the dichotomy—and associated value system—that underpins the carceral system: the us and them that “makes out of sight, out of mind” so pernicious.

Instead, in both scope and political stance, Marking Time is intended to stop you in your tracks. “This is an intervention,” Fleetwood says. The works are divided into three strands, looking at how being locked up affects time, space and physical matter. Among the works on show are the no-holds barred zine-like collages Ojore Lutalo made during his 22 years in solitary confinement; Sable Elyse Smith's whose multidisciplinary practice is informed by the tangible absence of a father imprisoned since she was a child; and anonymised visiting room portraits by Larry Cook.

There are some well-known names: George Anthony Morton, the first African-American painter to graduate from the US branch of the Florence Academy of Art or Keith Calhoun and Chandra McCormick, whose lifelong photography series documenting prison labour at the Louisiana State Penitentiary, commonly known as Angola, stunned visitors to the 2015 Venice Biennale. Many, though, are not. Having the substance of an exhibition trump any attempt at name-checking is a political act in itself. And, Fleetwood says, in staging this show, with a guest curator to boot (most are sorted in-house), MoMA PS1—under the new leadership of Kate Fowle—is indeed cementing an institutional commitment to engaging with both the issue of mass incarceration, and a broader audience base.

Sable Elyse Smith's Pivot II (2019) Courtesy of the artist, JTT and Carlos/Ishikawa

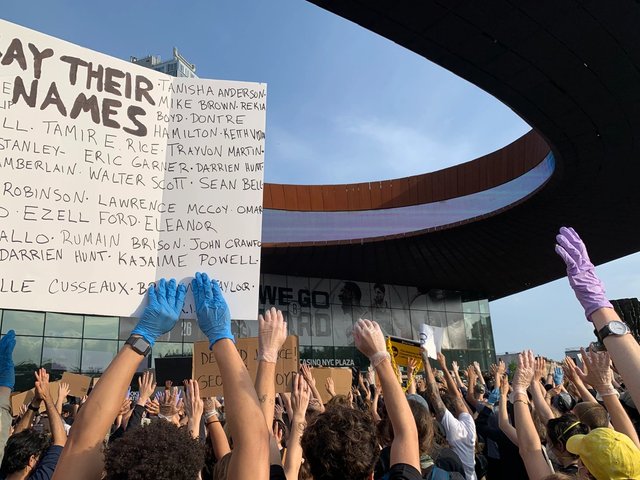

Of course, MoMA has, like much of the wider art world, come under renewed scrutiny in the wake of the most recent Black Lives Matter protests. Calls for the MoMA trustee Larry Fink to sever alleged ties with financial companies connected to private prisons have intensified. It is a conundrum that will only serve to highlight Fleetwood’s main contention that there is no abstracting art from politics. Systemic racism, it is clear, shapes not only the penal system but our cultural institutions too. With its dual focus on the people we shun and the objects we elevate, Marking Time represents a bold and urgent rethink of the museum itself.

• Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration, MoMA PS1, New York, 17 September-4 April